HM Treasury: Whitehall's great survivor

Many prime ministers have concluded that the Treasury is a structural block to economic growth, but none has found a way to replace it

(Note: this essay is longer than it needs to be and longer than it should be. But it would have taken me more time to make it shorter. I could have stripped out the anecdotage and extraneous information, but you deserve the sweet fruits of gossip mixed in to the roughage of analysis, so it is what it is.)

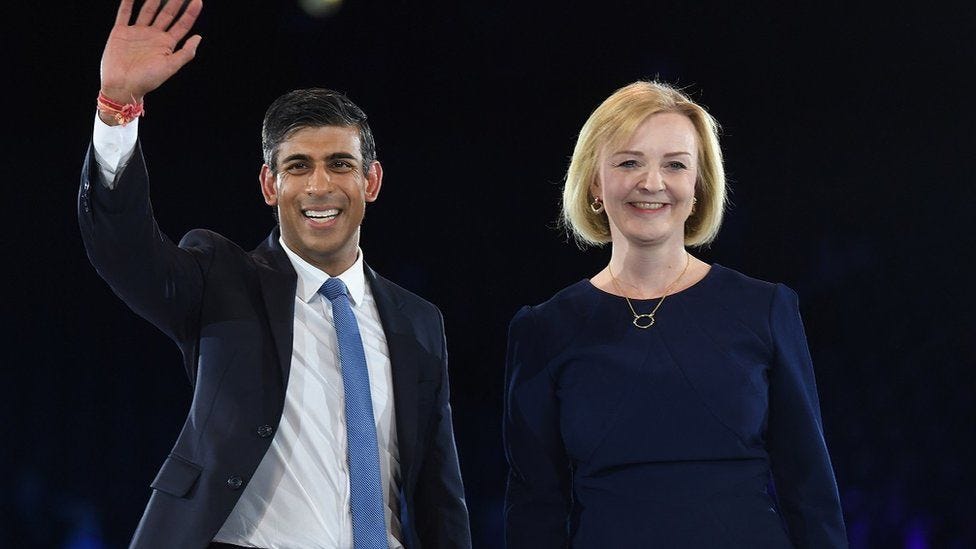

It is hard to believe that the great Truss vs. Sunak battle for the leadership of the Conservative Party was only three months ago. On the other hand, since Liz Truss was announced as the victor, it’s fair to say a lot has happened, including the death of our longest-serving monarch, the resignation of our shortest-serving (and shortest) prime minister, the defenestration of a chancellor and and economic policy between those two things, the recall of a former foreign secretary to steady this ship and be the ‘adult in the room’…

One of Truss’s themes during her summer of campaigning was a sustained attack on “Treasury orthodoxy”. It fitted in to her broader image as an iconoclastic Thatcherite disrupter, a provincial outsider seeking to disturb the status quo, but more specifically she defined Treasury orthodoxy as a view that expansionary fiscal measures—either a reduction in taxation or an increase in public spending—have no effect on growth or employment. This, she concluded, was the roadblock to faster growth after the great financial crisis of 2007-08, and it was time to switch course and use supply-side economics—lowering taxation, decreasing regulation and encouraging free trade.

There had already been a significant change in how economic policy is decided under Boris Johnson: his chief adviser Dominic Cummings had in February 2020 demanded that the chancellor, Sajid Javid, dismiss his special advisers and work instead with a joint policy advice unit with Number 10 Downing Street. This was a pill he could not swallow, and Javid resigned, saying to the media on his way out of Downing Street that “no self-respecting minister would accept those terms”. As a result of his departure, his second-in-command, the chief secretary to the Treasury Rishi Sunak, was promoted to be the new chancellor. Whatever happened to him?

Truss was threatening to go further. It was reported in July that she planned to create a powerful group of economic advisers within Number 10 Downing Street to challenge “Treasury ‘groupthink’”, but, contrarily, that the Cummings-midwifed joint No 10/No 11 economic unit would be abolished as it had not led to successful policy-making. In early August, she refused to rule out breaking up the Treasury entirely, saying she was “prepared to break eggs” and adding, “I do think the Treasury needs to change. And it has been a block on progress”.

In the end, she did not go quite that far. Some major changes were made: two days after Truss made her first cabinet appointments, including Kwasi Kwarteng as chancellor of the exchequer, she removed the Treasury’s top official, Sir Tom Scholar. The permanent secretary told the media that the chancellor had decided that “new leadership” was required and he wished the department well, but many were astonished and disheartened by the dismissal. Scholar, son of a permanent secretary, former British representative at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund and one-time chief of staff to Gordon Brown, was held in high esteem by his colleagues. His predecessor at the Treasury, Lord Macpherson of Earl’s Court, described Scholar as “the best civil servant of his generation”.

Liz Truss did not survive long enough as prime minister to have much effect on the machinery of government and the direction of economic policy. She did have time to dismiss her chancellor after 38 days in post, replacing him with the experienced former foreign secretary Jeremy Hunt, but she outlasted Kwarteng by only six days, and resigned after the shortest premiership in history. But her challenge to the position and influence of HM Treasury was hardly novel. The enormous power the Treasury wields has been the focus of anxiety, dissatisfaction and prime ministerial attempts to clip its wings for at least 75 years.

In 1947, the Attlee government, running a war-exhausted and beggared nation, reached a point of crisis. There had been an exceptionally cold winter and widespread fuel shortages, the cabinet was divided over the nationalisation of iron and steel, and on 15 July a provision of the Anglo-American Loan Agreement meant that sterling became convertible to dollars. That led to nations with sterling balances suddenly drawing on the UK’s dollar reserves, draining them with dangerous speed. The cabinet dithered for five weeks and then decided to renege on its agreement with the US government and suspend convertability.

The prime minister was widely blamed for the economic shock. Clement Attlee had been challenged for the premiership right after the general election in 1945, and now another plot developed. The president of the Board of Trade, the ascetic, pious and supposedly brilliant Sir Stafford Cripps, sought to demote Attlee to the Treasury and replace him with the foreign secretary, Ernest Bevin. He was characteristically little deterred by Bevin’s unwillingness to have anything to do with the conspiracy, and on 9 September was invited to a meeting with Attlee. The coup was nipped in the bud by extraordinary deftness on Attlee’s part: he soothed Cripps’s dissatisfaction by making him minister of economic affairs and giving him chairmanship of the cabinet committee on domestic economic policy in place of Herbert Morrison, the lord president of the Council and unofficial deputy prime minister. This was a masterstroke, neutralising Cripps and shrinking the influence of Morrison, as well as creating an alternative powerbase to the Treasury. Time Magazine described Cripps in his new role as “Britain’s economic dictator”.

Attlee’s relationship with the Treasury had always been a cautious one. When he had come to form his cabinet in July 1945, his initial intention had been to make Ernest Bevin, the former general secretary of the TGWU and wartime minister of labour, chancellor of the exchequer, while his choice for the Foreign Office was Hugh Dalton, Eton- and Cambridge-education, who had been under-secretary of state for foreign affairs from 1929 to 1931. The pair seemed almost typecast for their prospective roles: Bevin was a rough-and-ready bruiser who wanted his influence to be felt on the economy for decades; Dalton had a long pedigree in foreign policy in both war and peace, and combined an Establishment background with a strangely overbearing kind of bonhomie (although he was a trained economist). At the last moment, however, Attlee swapped the two round. There seem to have been several influences at work: Anthony Eden, the outgoing Conservative foreign secretary, strongly supported Bevin as his successor; but more influential may have been the king. George VI regarded Dalton as untrustworthy and two-faced (in which opinion he was hardly alone), and suggested that Bevin for foreign secretary and Dalton to the Treasury might be a more appropriate disposition. Attlee agreed.

This undoubtedly had an impact on the relationship between the Treasury and Downing Street in the early years of the post-war government. Attlee regarded Dalton as a “born intriguer” (though the former had beaten the latter to a permanent teaching post at the LSE in 1912), while he had a strong bond with Bevin, who, albeit condescendingly, returned the affection, referring fondly to the prime minister as “the little man”. But there was also the issue of Dalton’s performance as chancellor. David Marquand wrote in 1985 that the Treasury, after wartime dormancy, reestablished itself as the key driver of domestic policy after 1945 and Dalton “did not respond very skilfully”. Of the 1947 economic crisis, Marquand is unsparing. The chancellor “took no action to avert the crisis before it broke. It may or may not have been his fault. The fact remains that, after two years in the Treasury, the basic assumptions underlying his management of the economy were in ruins.”

Nor is this simply the verdict of historians. Herbert Morrison, Dalton’s cabinet colleague, delivered an unequivocal judgement in his autobiography. “The 1947 economic crisis was at root largely due to the faulty administration at the Treasury for which Dalton must be held responsible as head of the department.” The appointment of Cripps as an economic supremo was, therefore, potentially an answer to this difficult issue and a way of revitalising policy-making away from the axiomatic dead hand of the Treasury.

The experiment did not have time to show results. Cripps had been in office for almost exactly six weeks when Dalton, walking into the House of Commons to deliver his Budget statement, stopped to talk to a friendly journalist, and gave him a sneak preview: “No more on tobacco; a penny on beer; something on dogs and pools but not on horses; increase in purchase tax, but only on articles now taxable; profits tax doubled.” It seemed a harmless indiscretion as the chancellor would be on his feet at the despatch box in minutes, but the details were published in the early editions of the evening papers, while the stock market was still open. Dalton, described by Attlee as “a perfect ass”, took his mistake on the chin, and resigned. Cripps was appointed as the new chancellor and his role as minister of economic affairs was merged into the post.

When Winston Churchill returned to Downing Street in October 1951, he arrived steeped in suspicion for the economic machinery of Whitehall. This went back a long way. Churchill had been chancellor of the exchequer under Stanley Baldwin (1924-29), and one of his first major decisions had been to restore the Gold Standard. In his first Budget in April 1925 he had announced that the measure would be restored at pre-First World War parity of $4.86 to the pound, to the delight of Conservative colleagues and the Bank of England. But he now believed, a quarter of a century on, that he had received bad advice from Treasury officials and the Bank. Now, he sought to shake up the Treasury’s position. He turned to Sir Arthur Salter, political theorist and economist, who had been independent MP for the University of Oxford for 1937 to 1950 and returned to the Commons at a by-election as Conservative MP for Ormskirk. Salter had served as chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster in Churchill’s caretaker cabinet in May to July 1945 and now the returning prime minister offered him a choice: would he like to head a new department of economic affairs, taking some of the Treasury’s responsibilities, or would be prefer to serve within the Treasury as a minister under the chancellor?

This was a potentially dramatic moment. Churchill had some innovative notions of government which were relics of his wartime coalition. He had a very strong preference for familiar faces and his appointments in October 1951 had a strong whiff of “getting the band back together”. Eden of course returned to the Foreign Office and Churchill tried briefly to persuade him also to take on the leadership of the House, as he had during the war. Lord Cherwell, the prime minister’s old friend and scientific guru, became paymaster general with responsibility for nuclear policy. Another idea was that there would be cabinet “overlords”, senior figures with no direct departmental duties but who would supervise the work of several departments. For example, Churchill appointed Lord Leathers, a shipping expert who had been minister of war transport in the war, to be minister for the coordination of transport, fuel and power; in this role he sat in cabinet but the ministers whom he “supervised” (Geoffrey Lloyd, minister of fuel and power, and John Maclay, minister of transport) did not.

There were two disappointments to unravel Churchill’s attempt to constrain the Treasury. The first was that Salter opted to become a minister within the department, as minister of economic affairs, rather than setting up a new organisation, which he believed would have little influence in Whitehall. (He was also 70 years old, and can be forgiven for not having the stomach for a bitter territorial war within government,) The other was Churchill’s offer to his old colleague Sir John Anderson, who had been chancellor during the war, to become chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster and “overlord” of the economic departments (the Treasury, the Board of Trade and the Ministry of Supply). This would have reduced the Treasury to the status of a vassal, and a vassal of a Lords minister at that (Anderson had left the Commons in 1950 and was soon to be created Viscount Waverley). But Anderson, like Salter, both of whom had been civil servants before they were ministers, had no appetite for the idea, which he thought wrong in principle.

The Treasury was safe for another while. Churchill’s nostalgic plans had been frustrated and the new chancellor was not, as many expected, Oliver Lyttelton, a successful but unconventional businessman in the metal trade, but the rising star of Conservative domestic policy, R.A. Butler. Rab was still in his 40s and more than eager to make the best of this first major government office in a government characterised by old men whose best years were behind them.

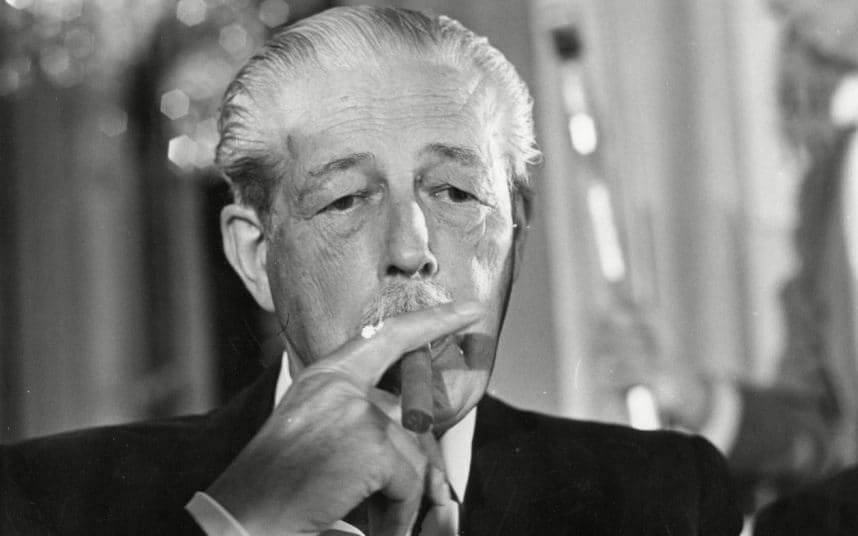

There were some internal changes within the Treasury under Macmillan’s premiership in an attempt, if not to disaggregate, then to clarify the department’s different and individually important functions. In 1962, the National Economy Group was formed to handle forecasts for the UK economy and Public Income and Outlay dealt with matching public expenditure to these forecasts. At the same time, the Treasury gained a second cabinet minister, the chief secretary, who existed to conduct negotiations over public expenditure. But this internal reorganisation did not solve the fundamental tension between day-to-day management of the economy with achieving long-term growth.

The election of Harold Wilson’s Labour government in 1964, after 13 years in opposition, brought a widespread appetite for significant change. Wilson had made the modernisation of the country one of the fundamental themes of his campaign, championing a planned economy, full employment and the harnessing of technological progress. He had witnessed the six-week experiment of Stafford Cripps as minister for economic affairs at first hand—he had succeeded Cripps as president of the Board of Trade—and judged it a success in organisational terms, given its attempt to separate planning from day-to-day management of the nation’s budget. Wilson was also an almost-obsessive manipulator of colleagues, taking extraordinary pleasure in balancing factions, playing off rivals against each other and devising intricate ways to distract challengers.

Harold Wilson did not distrust Whitehall as a matter of reflex: he had spent the Second World War as a temporary civil servant and had been offered a permanent position in the Treasury in 1945. But he was wary of the Treasury as an institution, and of the ability of the mandarinate to achieve the kind of progress and change he wanted to see. Moreover he resented the dismissal by the lofty generalists of the permanent secretary caste of specialist training like his (he was an economist), and intended to strengthen the technical abilities of the civil service as one thread of modernisation. He created five new departments at the beginning of his premiership: the Department of Economic Affairs, the Ministry of Overseas Development, the Ministry of Technology, the Welsh Office and the Ministry of Land and Natural Resources. That first creation was Wilson’s tool for breaking the Treasury’s power.

The idea of the Department of Economic Affairs, while drawing some lineal descent from Cripps’s six-week post in 1947, had been proposed in full in spring 1963 in a paper by Dr Thomas Balogh, the Balliol economist who advised Wilson. Balogh argued that “Treasury coordination is biased financial coordination” and that successful management of a planned economy required “an organisation dedicated to expansion”. Planning was regarded as the key to modernisation and success: described cattily by David Watt in The Spectator as “a word of the most powerful magic”.

There was a political driver behind this organisational split too. In contemplating the transition from opposition to government, Wilson had to think about personnel too. The shadow chancellor, Jim Callaghan, had been appointed to his role by Hugh Gaitskell in 1961, and was popular with the Parliamentary Labour Party. As a major player on the front bench, he could not easily be moved. But this left Wilson with the question of what to do with the deputy leader, George Brown, who had not shadowed a specific portfolio in opposition. Brown was in many ways brilliant: a tireless and passionate campaigner, and, once he had made up his mind, a fiercely loyal supporter. He was also an alcoholic, with a drinking problem that by 1964 was encroaching more and more into his professional life. However, creating a new department for economic planning not only offered him a role but gave to that role someone who would put formidable energy into making it work.

The Department of Economic Affairs took in almost all of the National Economy Group from the Treasury (see above), except the short-term forecasting team; economic planning staff from the National Economic Development Office; and the regional policy divisions from the Board of Trade. It was grouped into six division: Economic Planning; Industrial Division; Economic Coordination; Regional Policy; Private Office; and Internal Division. The DEA’s primary task, in the first months, was the drafting of the National Plan for economic development, which was published in September 1965 and set two ambitious targets for British industry: an annual growth rate of 3.8 per cent over six years and an increase in exports of 5.25 per cent each year to wipe out the balance of payments deficit.

With the loss of its economic functions, the Treasury was left as a finance ministry, responsible for public spending and currency issues. This was challenge enough: the balance of payments figures were dreadful, with a forecast deficit of £800 million, double what Labour had expected. The financial markets, assuming that a devaluation of sterling was unavoidable, were speculating heavily, but Wilson was determined that devaluation should be avoided at all costs. The prime minister’s focus on the currency at the expense of any other policy priority inherently undermined the DEA’s birth pangs.

Time Magazine observed that the relationship with the Treasury was all-important, but “the immediate result was tension between the two. Callaghan’s job, after all, required him to keep a cautious eye on the cash available in the Treasury, and Brown’s ministry was necessarily dedicated to expansion”.

The Treasury had inherent advantages. As a long-established department—the earliest extant Exchequer records date from 1129 and refer to earlier such records—it had prestige, and its alumni were spread throughout the civil service. At this point the Treasury had two (joint) permanent secretaries, Sir William Armstrong and Sir Laurence Helsby, both formidable officials. The cabinet secretary, Sir Burke Trend, was a former Treasury civil servant, as were his two predecessors, Sir Norman Brook and Sir Edward Bridges. Its staff in 1964 guarded their privileges jealously: papers were shared only reluctantly with the rival they referred to as the Department for Extraordinary Aggression.

Perhaps the greatest flaw in the DEA was that it was an organisation founded wholly on an ideological principle, that government planning was the secret to economic growth and prosperity. That made its future dangerously dependent on the success of that point of view. When the National Plan faltered into 1966 and 1967, it dealt a huge blow to the existence of the DEA. In July 1966, after Labour had won a substantial majority at the March general election, the cabinet considered devaluation again. George Brown had come round to supporting the idea, but was heavily outvoted and submitted a letter of resignation. Wilson pretended not to have received the letter and Brown was talked out of quitting, but the latter fell into a deep depression, feeling that he had lost face. In August, he was moved away from the DEA and given the job of foreign secretary, which, like so many, he had always coveted, but Wilson later remarked “He is a brilliant foreign secretary—until four o’clock in the afternoon”.

Brown had swapped positions with the relatively anonymous Michael Stewart, whose dry, academic manner failed to win union leaders over to his cause, and certainly the department felt the loss of its cheerleader, however erratic. Brown was still a force in the Labour Party, and still its formal deputy leader, whereas Stewart was virtually a technocrat. After a year, Stewart was replaced by one of Wilson’s protégés, Peter Shore, whose rise had been meteoric. The main author of Labour’s 1964 manifesto, he was selected at the last minute for Stepney at the age of 42 and joined the House of Commons at the election, but spent little time on the backbenches. In 1965, he became Wilson’s parliamentary private secretary, dismissed by Denis Healey as “Harold’s lapdog”, and in 1966 he again was the principal hand behind the Labour Party’s election manifesto. Joining the cabinet after less than three years in the Commons was remarkable, but, however brilliant he was (and indeed he was, an exhibitioner at King’s College, Cambridge, a member of the secretive Apostles and, in Patrick Cosgrave’s words, “the most captivating rhetorician of the age), he lacked the weight of Brown or even Stewart, and was clearly winding the DEA down.

In April 1968, prices and incomes policy was transferred to the new Department of Employment and Productivity under Barbara Castle, whose star was in the ascendant. Harold Wilson admitted in the House of Commons that “I considered very seriously whether Departmental responsibility should go to the Treasury as part of demand management”, but on reflection:

I felt the linking the general co-ordination with the day-to-day work of dealing with individual wage settlements would be more likely to get the right answer in individual cases and to make it more possible, particularly if one could start early enough in a particular wage claim, to link productivity with any wage settlement.

The machinery of government changes signalled to MPs on all sides that the DEA experiment was over, but it was not formally ended yet. Jock Bruce-Gardyne (Con, South Angus) asked the prime minister if the DEA would be absorbed into the Treasury, and, being told no, pressed his argument.

Now that the Department of Economic Affairs has lost the prices and incomes policy, what other purpose does it serve, apart from providing the right hon. Member for Stepney [Peter Shore] with a car, an office and a fat salary? If the Prime Minister needs his right hon. Friend’s support in the Cabinet, would it not have been more economically provided by making him Minister without Portfolio?

Wilson, never one shamed by giving misleading answers, insisted that the DEA still had an important role, “ensuring by the co-ordination of the industrial Departments that the real resources are available to meet the requirements of the Chancellor’s budgetary policy, both as regards productivity and as regards exports and import replacement”. The Treasury, he went on, had its hands full with “not only general financial policy, budgetary policy, but expenditure policy and international liquidity policy”. But these were answers for political consumption, which did not reflect the reality within Whitehall and the cabinet.

The death of the most sustained organisational attempt to dilute the Treasury’s power in Whitehall came in October 1969. The vultures had been circling for some time. In January, John Biffen (Con, Oswestry), a free-market Tory in sympathy with Enoch Powell’s economic ideas, had asked if the DEA would now be wound up. Wilson, at his light-hearted but sharp-tongued best, waved him away.

I understand from the hon. Gentleman’s pronunciamento and his support of a certain right hon. Gentleman, whom we do not often see on his side of the House, that he is so opposed to all economic planning, even to the intervention which was undertaken by the previous Conservative Government, that I would naturally not expect him to appreciate the virtues of the Department of Economic Affairs.

Wilson may have felt some embarrassment. After all the DEA had been a potent symbol of the different way Labour would conduct economic policy after 1964. Certainly opposition politicians seized the opportunity to twit him about it. Edward Heath, hardly the world’s most powerful or funniest orator, weighed in at his party conference at Brighton.

What has emerged from the whole of this, to the great benefit of the nation, is the death—no, that would be wrong—the constitutional abolition of the Department of Economic Affairs. It has been dead for a long time; it has only just now been abolished. You will remember the origin of the Department of Economic Affairs—it was conceived in a taxi in a three-minute journey to the House of Commons in order to give a job to George Brown. It seems to me that that must be pretty well the most unproductive thing ever to come out of the back of a taxi—so far.

It must have been uncomfortable for Wilson to read, because it was rather accurate. After five years, the Treasury had won. The battle had been fiercely fought, and the prime minister had gone further than any of his predecessors, but the plain facts were that the Department of Economic Affairs and the National Plan were dead. The belief in central planning survived, though it would soon be dealt a series of heavy blows, but for now politicians on both sides would be left with the Treasury as the means for pursuing it.

Edward Heath was a singular prime minister. He was not expected to win the general election in June 1970, then did so with a handy majority of 30, and he pulled the roof down on his own government less than four years later by calling an election on the question “Who governs?” in February 1974. (Never ask that question: the answer will always be “Not you”.) He is the only prime minister so far to have served as chief whip, the only prime minister since Balfour to be unmarried, the highest-ranking officer in the armed forces to serve since the 19th century (he left the Army a lieutenant-colonel), the only one to captain a winning Admiral’s Cup team and the only one to conduct the London Symphony Orchestra. He was also, I would argue, one of the least-suited prime ministers by personality of the 20th century, and probably (EEC accession aside) one of the most unsuccessful.

One other quality Heath possessed was that he took a genuine interest in the machinery of government, an interest that was earnest and straightforward, unlike Wilson, who liked to use departmental structures to manage his colleagues. As leader of the opposition after 1965, reflecting the mood of the times, he had pursued a very managerial, professional approach, keeping front bench changes to a minimum and trying, where possible, to allocate portfolios to MPs with real subject expertise. For example, the former prime minister and foreign secretary Sir Alec Douglas-Home shadowed foreign affairs, Quintin Hogg, an experienced lawyer and QC, was shadow home secretary, and Robert Carr, shadow employment secretary, had worked in his family engineering firm. Heath’s choice for shadow chancellor—the post he had held before the party leadership—had been Iain Macleod, one of the best speakers and the sharpest minds on the front bench and a championship-level bridge player.

As many ministers as possible carried their portfolios from opposition into government, and Macleod duly went to the Treasury in June 1970. Elsewhere in Whitehall, Heath was undertaking a massive machinery of government overhaul, mainly aimed at creating two “super-departments”, the Department of Trade and Industry and the Department of the Environment, but he made no move to change the Treasury’s responsibilities or reach. But there was one huge change in the Treasury’s circumstances. After a month in office, Macleod died of a heart attack, and was replaced by Anthony Barber (who had been a Treasury minister from 1959 to 1963). Barber, while diligent and able, was a second-rank political figure compared to Heath and Macleod, and his appointment meant that for the rest of the government, the Treasury would be quietly subservient to Downing Street. Macleod as chancellor would have been a very different proposition.

Heath had been elected on a relatively radical manifesto. It dwelt heavily on finding a new way of governing, taking expert advice and reaching sensible, informed conclusions, and there were references to free enterprise and tax reductions. On nationalisation, it pledged not to carry the process further, and to begin to wind down the state’s involvement. In truth there was no fundamental change. The government’s nationalisation policy fell apart as soon as 1971, with the state purchase of elements of Rolls Royce, and the wider economic policy fell apart with the beginning of the Barber Boom in 1972, leading to soaring inflation and the re-introduction of a prices and incomes policy. The Treasury was wholly in his thrall. When he left office in March 1974, after a last-minute attempt to forge a shabby coalition with Jeremy Thorpe and his Liberal colleagues, there was little regret. Setting aside the UK’s accession to the European Economic Community on 1 January 1973, it had been a dismal, confused, timid and rudderless administration.

After Labour returned to power in March 1974, strengthening their position slightly at a second general election in October, the new chancellor was the man who had shadowed Barber since 1972, Denis Healey. He was a political heavyweight, a strange mixture of high intellect and crude abuse, never troubled by self-doubt and easily the most powerful force in the cabinet: Harold Wilson was tired and suspicious, and would resign in 1976; Roy Jenkins had reluctantly returned to the Home Office but had lost what lukewarm affection he had ever had for the Labour Party; Jim Callaghan was in the semi-detached Foreign Office; while Peter Shore and Tony Benn, both anti-Common Market in a divided party, were looking more eccentric and divorced from the mainstream.

One of Heath’s “super-departments”, the Department of Trade and Industry, was broken into three: the Department of Trade (Shore), the Department of Industry (Benn) and the Department of Prices and Consumer Protection (Shirley Williams); Energy had been separated in January 1974 in response to the coal and oil crisis. Wilson’s carve-up looked like it was demolishing one of the Treasury’s only potential rivals in the formation of economic policy, but that was not the intention. Planning was still in vogue on the left, and Benn wanted to pursue the Labour manifesto in spirit and to the letter, seizing the “commanding heights of the economy” and working with industry across the UK to provide government support where necessary. The department’s white paper, The Regeneration of British Industry, pointed the way to the Industry Act 1975, creating the National Enterprise Board, which supported government-selected sectors like electronics and computers, as well as assisting failing companies. It took substantial shareholdings for the government in many companies, essentially spreading nationalisation across the economy.

In different circumstances, a strong Department of Industry with a remit of national planning and discretionary state investment could have rivalled the Treasury in terms of taking the initiative in economic policy. But Healey was a formidable figure, after 1976 supported by a prime minister who had himself been chancellor and knew how isolated the chancellor could feel in cabinet. And Tony Benn, who had not long before abandoned his old, class-identifying style of Anthony Wedgwood Benn, was beginning to move towards the left and diminished relevance. His successor, Eric Varley, was less eccentric but also of less weight, popular enough in the party and diligent but nowhere near the first rank. So the Department of Industry made no real inroads into Treasury power.

Margaret Thatcher arrived in Downing Street in May 1979 as the most self-consciously disruptive prime minister of the century. Although she quoted the soothing prayer of St Francis of Assisi outside the door of Number 10, it was very clear that she had a plan which she wished to pursue to transform the UK economy, and equally clear that by 1979 she still did not have a majority of true believers in her cabinet. Indeed, many of her first team opposed her politically and some disdained her socially and personally: Lord Carrington, Lord Soames, Sir Ian Gilmour, Francis Pym, Jim Prior, Peter Walker. Even her deputy, Willie Whitelaw, was no ideological soul mate, but had made his decision on her election in 1975 to support her absolutely.

Thatcher did, however, have a strong group of supporters in the Treasury. In opposition, her key economic advisers had been Sir Geoffrey Howe, the shadow chancellor, and Sir Keith Joseph, the head of policy in the shadow cabinet. The two were very different. Joseph, who had won a first in jurisprudence at Magdalen College, Oxford, then become a fellow of All Souls, was a slightly distracted intellectual who worried deeply about things, and had revealed in 1974 that he realised he had never been a Conservative at all until that moment. He had an ingrained Jewish sense of guilt and an unstoppable honesty. Ian Gilmour thought he was “a Rolls Royce brain without a chauffeur”, while Macmillan, who had an unpleasant tendency towards anti-semitism, said he was “the only boring Jew I’ve ever met”. But Thatcher regarded him as “the greatest man in England”.

Howe was a successful lawyer of Welsh origins (he was born in Port Talbot, also the birthplace of Richard Burton, Anthony Hopkins, Michael Sheen and Speaker George Thomas, though he lacked their distinctive tones). He was unquestionably able, first winning an exhibition to read classics at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, before switching to law, and taking silk in 1965. He was an effective law officer from 1970 to 1972, then joined Thatcher in the Heath cabinet as a second minister at the DTI. Howe had shown interest in Enoch Powell’s economic thinking in the early 1960s, and by 1975 Thatcher saw him as a reliable fellow traveller with a solid if undramatic manner at the despatch box.

Many expected Joseph to be named chancellor in 1979, despite his roving, portfolio-less brief in opposition, but there is no evidence that Thatcher hesitated significantly in picking Howe. Joseph had the more intellectual bent, but Howe was a very solid exponent of policy and was reliable in front of the media. Nevertheless, Joseph went to the Department of Industry. Howe was supported by faithful monetarist lieutenants: John Biffen was chief secretary, Nigel Lawson became financial secretary and the two ministers of state were Peter Rees, an able tax barrister, and Lord Cockfield, a former civil servant and businessman with a penetrating, logical intellect.

For all her iconoclasm, Thatcher never sought to reform the Treasury or cut it down to size. For her first parliament, Howe was a loyal and trusted ally as chancellor, who often stiffened her resolve rather than the other way round. When she appointed Nigel Lawson as his replacement in 1983, disappointing Patrick Jenkin who somehow thought himself in the running, she knew she was picking someone who shared her views on the immediate tasks ahead: privatisation, deregulation, reducing taxes and simplifying the tax codes. Lawson had worked at The Financial Times and The Sunday Telegraph, and was regarded, in the parlance of the time, as bone-dry.

The Thatcher/Lawson axis survived happily enough for many years, including “Big Bang”, the 1986 deregulation of the City of London. But after the 1987 general election, in which Lawson performed well, she began to view him as a potential rival. She was probably wrong; I have never seen any evidence that Lawson had designs on the premiership, while, in his final Mansion House speech in 1989, he may have given away the true nature of his ambition and achievement. “The people of Britain… have rediscovered the spirit of enterprise. And that is the greatest prize of all.” Lawson wanted a revolution. He simply had no interest in being prime minister.

(I also wonder, to my sorrow, if the Conservative Party in the late 1980s would have accepted a Jewish leader, even if Lawson was not obviously observant and his family had come to the UK from the Baltic states in the early 20th century. While Thatcher liked Jews, being devoted to Joseph, and promoting not only Lawson but Leon Brittan, Malcolm Rifkind, David Young and Michael Howard, her party was less relaxed. Macmillan remarked that her cabinet had “more old Estonian than old Etonian”, which might have raised a smile in White’s in the 1920s but by the 1980s had a noxious whiff. The meeting of the 1922 Committee after Leon Brittan’s resignation in 1986 saw some unpleasant innuendo, and John Stokes, the Conservative MP for Halesowen and Stourbridge, remarked that Brittan should be replaced by “a red-blooded, red-faced Englishman, preferably from the landed interests”. Everyone could read between the lines. Edwina Currie, the able but confrontational junior health minister, was described as a “pushy Jewess”. Lawson might have faced considerable, if barely vocalised, opposition. But I digress.)

Thatcher began to distrust the Treasury as her view of Lawson became more jaundiced. In early 1989, she reappointed as her personal economic adviser Professor Sir Alan Walters, who had served her from 1981 to 1983, and was a reliably monetarist thinker who disliked the notion of the European Monetary System, an exchange rate arrangement linking the EEC’s currencies. Lawson believed that the UK should join the EMS, while Walters described it in public as “half-baked”, while Thatcher had affirmed her belief that “you cannot buck the markets”. This started to undermine Lawson’s exchange rate policy, since the markets could not be sure that the prime minister would back him consistently. The situation was untenable, and in October Lawson demanded that Thatcher dismiss Walters, or he would resign; there had to be full agreement, demonstrated publicly, between prime minister or chancellor, or the relationship simply did not work.

Thatcher had conducted a significant reshuffle only a few months before and was not keen to make further big changes, but her conduct in the hours after Lawson’s demand, when she had rather weakly defended his position in the Commons, suggested she had tired of her long-serving chancellor. This was a factor in her close relationships. She had started to find Howe, foreign secretary until the summer reshuffle, irritating, and had moved him to the empty dignity of deputy prime minister. Now she seemed content to let Lawson go. It was a sign of her growing unpredictability and caprice, and, perhaps, the absence of anyone to advise her candidly: Whitelaw had retired from ill-health in January 1988, Sir Robert Armstrong, the cabinet secretary, had stepped down the year before, John Wakeham, a masterly chief whip and then leader of the House of Commons, had taken over his own department in the July reshuffle. She needed a voice of reason, but there was no-one there to give it.

In the end, this did not even become a successful show of strength against the Treasury. Shortly after Lawson quit, Walters resigned too. However, Thatcher did appoint the inexperienced John Major as the new chancellor. He had been foreign secretary only for four months and there was anxiety that he would be a Number 10 puppet. But Thatcher’s authority was deteriorating, and within 13 months she would be gone.

John Major was prime minister for six-and-a-half years—a longevity it is easy to forget—but had only two chancellors in that time. His first was Norman Lamont, his chief secretary as chancellor (and financial secretary when Major himself had been chief secretary) and his campaign manager for the leadership. But the two were not friends, or ideological allies. Lamont was a public school Cambridge graduate from a professional family who had worked for N.M. Rothschild and Sons before entering Parliament in 1972, while Major came from famously humble beginnings. And Lamont was a peculiar man; Thatcher had made him a minister in 1979 but he had not reached the cabinet until 1989, and then only as chief secretary. He was genial but had a strange reckless streak and a decent helping of vanity and unwillingness to apologise. In 1985, he had been left with a black eye after leaving the house of Olga Polizzi with her lover in pursuit, a story on which gossip columnists pounced. Lamont said the incident was “innocent but complicated”. Later rumours reported that he had been caught wearing said lover’s pyjamas.

If Major and Lamont were not close, the prime minister had no reforming zeal when it came to the Treasury, a department he’d served in and whipped for. In any event, there were pressing policy issues which crowded out anything else. Five months after his surprise election win in 1992 came Black Wednesday (16 September 1992), when the UK had to withdraw sterling from the Exchange Rate Mechanism. The story is told elsewhere, but the crisis shattered the Conservative Party’s reputation for sound economic management. Lamont claimed that ERM membership had been a success and by 1992 it had done its job of bringing inflation under control: “the ERM was a tool that broke in my hands when it had accomplished all that it could usefully do”. He was not alone in that analysis, but he either failed to see the political damage or thought he could ignore it. Bad luck attaches to the unfortunate, however, and minor but embarrassing media stories began to cling to him throughout the autumn, from his being in arrears on his credit card (hardly a good look for the chancellor of the exchequer) to a sex therapist renting a flat he owned. All true, all footling, all damaging.

Lamont’s downfall was largely of his own doing. Never especially deft with the media, he was asked at a press conference during the Newbury by-election campaign in 1993 which remark he regretted more, saying that he could see “the green shoots of recovery” or telling people that he had been “singing in the bath”. He responded by quoting the Edith Piaf standard Je ne regrette rien, which might have been dryly amusing in his head but seemed lofty and disdainful on camera. Major had had enough. On 27 May, he offered Lamont the post of secretary of state for the environment—a very obvious demotion—but the continued use of Dorneywood, the chancellor’s country residence in Buckinghamshire, and a flat in Admiralty Arch. Lamont was not to be bought. He resigned from the government, and on 9 June made a savage resignation statement accusing the prime minister of being “in office, but not in power”.

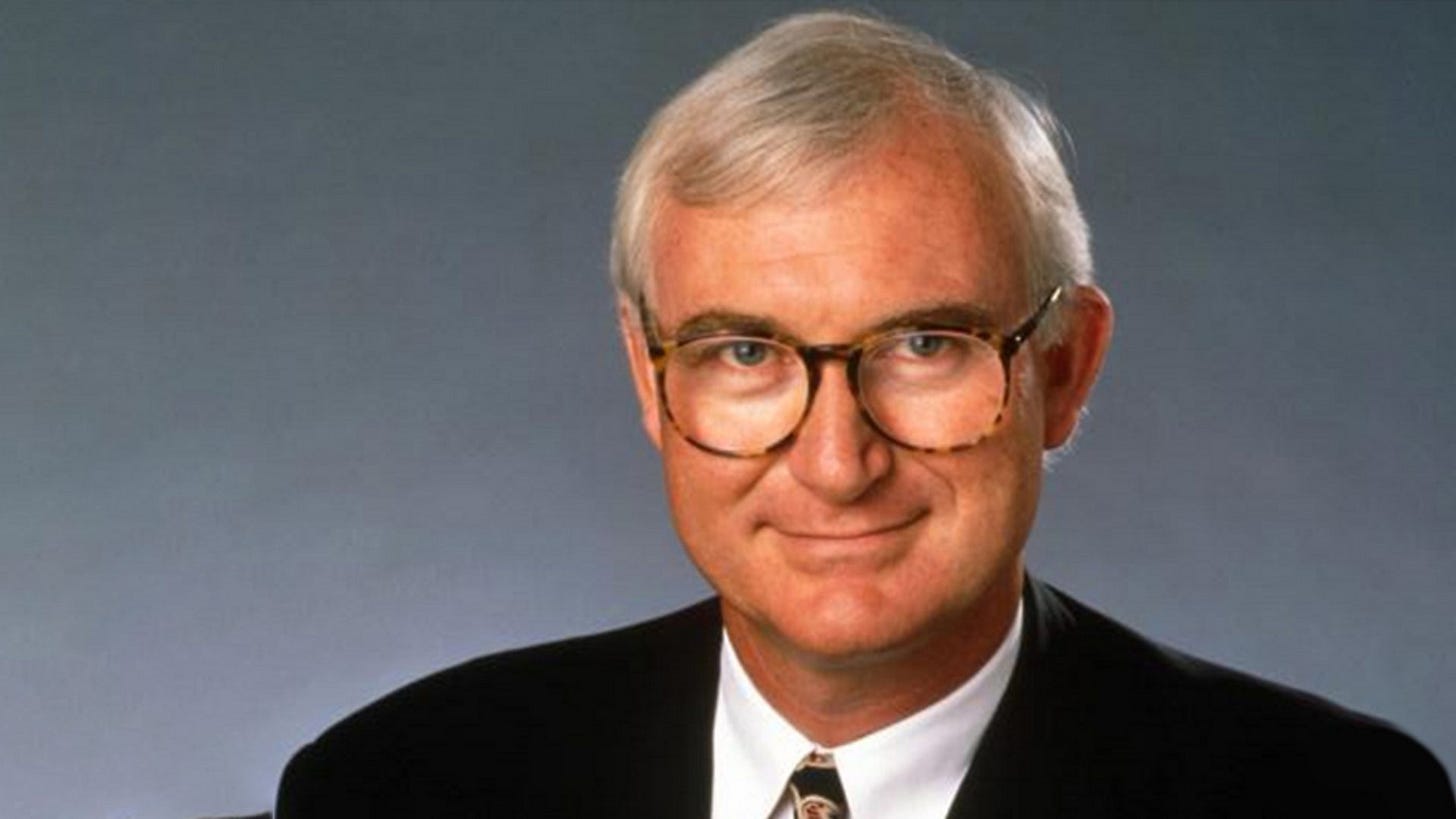

The new chancellor was Kenneth Clarke, formerly home secretary. He was the obvious choice: calm, relaxed, jovial and vastly experienced (he had been in cabinet since 1985). He had been considered for the Treasury in 1990 but had no ministerial experience in the department; now his seniority made up for that. It is not easy to see whom else Major could have appointed. Michael Heseltine, the trade and industry secretary, had the stature but was still on leave following a heart attack that summer; Douglas Hurd was an unlikely finance minister; the job would probably already have been Chris Patten’s had he not lost his seat in Bath at the 1992 election, but he was ensconced as governor of Hong Kong. Clarke proved a sound choice, a confident public speaker and a competent manager who presided over a period of economic growth and prosperity. There was no time to think about structural reform of the Treasury now.

The Labour victory of 1997 saw one of the most heavily trailed Treasury appointments ever, as Gordon Brown became chancellor after five years shadowing the department. He had been promised not only the post of chancellor but a virtual free rein over domestic policy when he and Tony Blair had made their infamous pact over the party leadership in the wake of John Smith’s death in 1994; the so-called “Granita pact”, after the Islington restaurant where it was agreed, stated that Brown would control economic and social policy, and that Blair would stand down as prime minister in his favour during a second term (it would not work out quite like that—Brown would write in his memoirs, “The restaurant did not survive and ultimately neither did our agreement”).

Brown came to the Treasury in a stronger position than any Labour chancellor before him. The economy was in good shape, and, to allay any fears the electorate might have, he had committed to sticking to the Conservative spending plans for the first two years. In his first days, he gave the Bank of England operational independence over interest rates, and transferred its regulatory responsibilities to the new Financial Services Authority. So far from having its wings clipped, this was the Treasury in excelsis. Brown had a powerbase and a policy reach that no chancellor had possessed since at least Roy Jenkins in the late 1960s, and while Blair was a popular and ambitious prime minister, he lacked Brown’s appetite for grinding detail. For a while, there was happy coexistence, and it seemed as if nothing could go wrong.

One insight into the position of the Treasury in the Labour government is provided by Patricia Hewitt, who was trade and industry secretary from 2001 to 2005. A highly able but nannyish Australian—her accent unmasked itself when she was agitated—with a hard-left background, she had been under supervision by MI5 in the 1970s. She then tacked sharply to the modernising centre, working for Neil Kinnock and John Smith before being elected to the Commons for Leicester West in 1997. She was appointed a Treasury minister after only a year, then became minister for small business and e-commerce at the DTI. After the 2001 election she became secretary of state. She felt the department “just wasn’t working” and that the top team of officials was “a shambles”.

What I also learnt in that process was that the brilliant people at the Treasury, who’d been crawling over my £5 billion budget at DTI—most of which was ring-fenced to science—had waved their hands at the £100 billion that had been given to Health and the NHS and had no idea what was happening to the money, and hadn’t bothered to actually take any notice of it.

As a junior minister, she had observed that the DTI harboured deep resentment towards the Treasury as a kind of lowering, bullying elder sibling. This fed into a lack of confidence in their own department, which was corrosive in the Whitehall jungle.

I just thought ‘Look, it is what it is, the Treasury is the senior department, you’re just stuck with that fact in our system of government, they’re the macro department, we’re the micro department’, and I coined the phrase that ‘We have to be the supply-side partners to the Treasury.’ And once Tony appointed me, that’s what I said to all my officials, I said, ‘We are going to work with the Treasury. They may be difficult, but we are going to work with them.’ And I said the same to my special advisers.

Hewitt’s observations show that the role of the Treasury, and its potential over-dominance, were a widely noticed feature of the Labour government. Partly, of course, this was a function of a chancellor who had been granted, and would accrete further to himself, extraordinary power and influence beyond the strict fiscal and economic issues on the government’s agenda. Of her own time at the Treasury, Hewitt pointed out that giving the Bank of England control over monetary policy left a degree of spare capacity at Great George Street. “I thought ‘OK, so Treasury has now got time to do lots of interesting things, including putting their fingers into every other department’s pies’, which was about right.”

She also remarked on the quality of the civil servants with whom she dealt at the Treasury. They were young—the current average age is 34—and intellectually impressive, but rather disconnected from the real world and lacking in people skills: “unbelievably bright, but they had no social skills or polish at all”. She contrasted this with equivalent officials in the Diplomatic Service (where the average age now is 43), “both very bright, but, you know, the Foreign Office guy was kind of smooth and had impeccable social skills, and the other one was kind of geeky”. This was not merely a matter of social graces, but it meant, in Hewitt’s view, that the Treasury was bad at cooperating with other Whitehall departments, at the same time as expanding its reach.

Nothing lasts forever, not even the happiest political marriage. By the end of the second New Labour government, Brown was chafing at Blair’s failure to step aside, and Blair was growing weary of the moody territorialism of his Downing Street neighbour. To break the tension, a plan was devised whereby Brown might become foreign secretary after the 2005 election, and, more relevantly, the Treasury would be dismembered. The idea was set out in a 200-page memorandum from Lord Birt, Blair’s strategic adviser and former director-general of the BBC. With the assistance of the chief analyst at the Number 10 Strategy Unit, David Halpern, and another senior Downing Street aide, Gareth Davies, he drew up a plan to separate the Treasury functions into a finance ministry in charge of taxation, financial services and international markets, and a new US-style Office of the Budget and Delivery, either as a standalone department or under the aegis of the Cabinet Office. Later, to make the changes more amenable to Brown, it was proposed that competition policy would move from the DTI to the finance ministry, and the OBD would be a separate entity but within the Treasury.

This proposal—codenamed “Operation Teddy Bear” to make it sound harmlessly benign—was not so much designed to cut the Treasury down to size as to improve coordination at the centre. Blair had become frustrated by his inability to push policies forward, despite the use of the Policy Unit, the Strategy Unit and the Delivery Unit, and was aware that these small prime ministerial teams would always be outgunned by the Treasury. One anonymous supporter of the plan explained the motivation:

A refocused Treasury could have done the finance function better, focusing more on how much a proposal would cost. Even on an issue such as public sector pay there was a overlap between the Treasury, the Cabinet Office and No 10. There was a huge amount of replicated work. If you were sitting in the Home Office you had the Treasury doing crime, the strategy unit looking at the same issues and Downing Street doing something similar. There just seemed to be 27 varieties.

But the courage to pursue the most radical machinery of government transformation for generations failed Downing Street. Brown, approached tentatively, flatly refused to countenance the changes: he was seen as indispensable to the 2005 election campaign, and such a provocative restructuring was shelved. Brown would remain chancellor until he succeeded Blair as prime minister in 2007, after more than a decade at the Treasury, a tenure not matched since Nicholas Vansittart in 1812-23.

We have nearly (you will be exhaustedly pleased to hear) come full circle. The coalition government formed in 2010 made no attempt to change the remit or influence of the Treasury. It was almost as central as under Brown, as the chancellor, George Osborne, a shrewd political operator with youthful energy, was a very close ally of David Cameron. The chief secretary was a Liberal Democrat: very briefly David Laws, then Danny Alexander, not of the same stature as his colleagues. However the chancellor’s deputy was still a member of the so-called Quad, the group of four ministers—prime minister, deputy prime minister, chancellor and chief secretary—who made all the critical decisions. This arrangement entrenched the power of the Treasury, as it had resources to support its two leading ministers which far outstripped those available to the deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, and even the prime minister. But it was a harmonious group: if Cameron and Osborne were close, then Cameron also found Clegg an easy personality, while Alexander became closer to his leader Clegg over the five years of the parliament.

Theresa May appointed the foreign secretary, Philip Hammond, to be her chancellor of the exchequer when she became prime minister in 2016. It was perhaps an omen for their relationship that she had beaten him to the selection for her parliamentary seat, Maidenhead, in 1997. Hammond, naïvely if understandably, expected the kind of central role in overall policy formulation that Osborne and Brown had had. But Osborne had been devoted to Cameron, while Brown had possessed a standing in the party and a sheer force of will that assured him of titanic influence. Absent these things, Hammond’s tenure at the Treasury was a perfect demonstration that sometimes institutional relationships are entirely subordinate to personal ones. Talking after his retirement to the Institute for Government, he remarked:

I remember asking her whether she planned to make any changes to responsibilities or roles or privileges, just to make sure that I wasn’t being offered a job that might not have been quite what it seemed. She said no. She did of course then appoint a deputy prime minister, which was not quite living up to the spirit of what she’d said to me at that time.

It was a significant disappointment, but it should have been the opportunity for Hammond to break out the big-boy pants and make the best of it. He claims their working relationship was “fine” but stresses that they barely knew each other in anything except a professional capacity, although they had been exact contemporaries at Oxford (May read geography at St Hugh’s, Hammond PPE at University College). He also says that he did not adopt a “new direction” at the Treasury. He had, of course, been Osborne’s deputy in opposition and therefore was steeped in the origins of the coalition’s economic policy. But the change of leadership allowed him to relax some of Osborne’s more ambitious fiscal targets and bring a sense of greater realism to Treasury policy.

Hammond’s description of life as chancellor sounds like it conceals a great deal. Sir Anthony Seldon’s book May at 10, an analysis of her premiership, quotes the former chancellor raging at the prime minister’s joint chiefs of staff, Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill:

They were pure poison. It was simply the way that they were; they were a toxic mix in No 10. I knew Fi well, she’d been my press officer when I’d been an opposition spokesman. The relationship worked well when I was the boss but, once she was in power, she was quite intolerable. Nick hated me and made my life difficult wherever he could. The two of them were always leaking to the media that I was going to resign.

This was hardly a good foundation for the relationship between Number 10 and Number 11. In public Hammond was slightly more circumspect, observing that “Although it’s difficult to remember this now, I had a good relationship with Fiona Hill, who was very close to” May. But Seldon’s book suggests that Hammond was not a passive victim, speaking down to the prime minister when her limited expertise in economic policy exposed itself. Worse, “Word came back to No 10 that Hammond would be openly contemptuous in meetings at the Treasury of ‘Nick Timothy’s wacky ideas’.” However one looks at it, it was a relationship riddled with dysfunctionality and ill will.

By late 2017, the newspapers were gleefully trumpeting stories of utter toxicity. There had already been rumours before that year’s general election that Hammond would be sacked, and May had not gone out of her way to stamp them out. She had, however, kept him on, but as the autumn progressed the more Brexiteer elements of the party, sensing Hammond’s lukewarm support, began to demand his head, and the name of Michael Gove was frequently bruited as a more ideologically sound successor.

May did not seek to make structural changes to the Treasury. One can forgive her that: she had to attempt to implement the result of the Brexit referendum, and, after the 2017 election, scrape together the remnants of her authority which had simply melted away from the poll-conquering days of earlier that year. She did fight back through the Whitehall machine, however, revamping the cabinet committee system in October 2016 to use her appetite for details and sheer hard work to impose prime ministerial power. She had inherited from David Cameron a system of 10 committees, 10 subcommittees and 11 “implementation taskforces”, and she carried out radical surgery on this to produce just five committees, nine subcommittees and seven taskforces. The cabinet committees were: economic and industrial strategy; European Union exit and trade; the National Security Council; social reform; and parliamentary business and legislation.

Crucially, the prime minister chaired four of the five committees, the last being chaired by the leader of the House of Commons (David Lidington then Andrea Leadsom). By contrast, Hammond as chancellor chaired only two subcommittees, the economic affairs subcommittee of the economic and industrial strategy committee, and the cyber subcommittee of the National Security Council. This may seem like a trivial bureaucratic issue, but much of government’s hard yards are done in cabinet committees, and, importantly, the prime minister can decide what should be considered where. In effect, May’s administrative coup de main robbed the Treasury of almost all initiative within the central government machine.

Hammond was not powerless. However, quizzed by the IfG, he described the power of the Treasury during his tenure as chancellor in relatively circumscribed terms.

Your ability to influence things across government rests on the Treasury’s need to have signed off on projects of every type. Now, that doesn’t mean you get a veto, and nor should it, but it does mean you get an early opportunity to look at policy and to negotiate with spending ministers to get quick and clear passage through the Treasury. And it’s often possible to get sensible tweaks to policy.

“Early opportunity” to “look at” things, “negotiate” and get “tweaks”. It was hardly Gordon Brown’s “great clunking fist”, to use Tony Blair’s phrase.

There were still those who urged May to reform the Treasury. The prime minister had unveiled an industrial strategy—a phrase so redolent of the Labour Party’s days in office in the 1960s and 1970s—and had included the words in her rebranded and restructured business department, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy which had merged the old departments of Business, Innovation and Skills and Energy and Climate Change. Dr Craig Berry, a Sheffield academic who sat on the independent Industrial Strategy Commission, was explicit that “to succeed, and last, May’s industrial strategy must address the Treasury’s dominance directly”.

Berry’s suggestion was not, ironically, to take away power from the Treasury but to enhance its powers and achieve revolution from within. The commission’s report proposed that an industrial division be created within the Treasury to take ownership of the government’s Industrial Strategy and “act as an institutional hub for the coordination of all policies encompassed by the strategy across government”. This change of perspective would, the commissioners felt, flip the aspects of the Treasury which held growth back into tools for promoting the strategy, using its highly trained and able officials and control over public spending. In addition:

The new Treasury division would operate strategic, cross-government action to decarbonise the economy, produce a healthier workforce, generate long-term investment and build the UK’s export capacity (among many other things).

It was a bold and radical idea, even if it did feel somewhat as if it had been drafted by a less unmoored Tony Benn. But May’s appetite for structural reform had, it seems, been sated after her initial burst of activity with machinery of government changes and an overhauled cabinet committee system. By 2017 and certainly 2018, reality was simply coming at her too quickly.

So we come to Boris Johnson’s premiership and the creation of the joint economic unit in Number 10 and Number 11 Downing Street. His chancellors, Sajid Javid, Rishi Sunak and Nadhim Zahawi, were not of a stature close to his, and never challenged him in a way which mattered to the notoriously unfocused prime minister. Johnson governed through vibes as much as concrete policy, and once the Covid-19 pandemic struck in March 2020, the government went on to an emergency footing which essentially required the Treasury to do whatever was necessary to stave off complete collapse. Dominic Cummings, his sinister Mekon, had far-reaching ideas for reform of the civil service, and his blog continues to parade his thoughts, but Cummings thought in much more radical terms than balancing or rebalancing departmental responsibilities. He believed that the model of a permanent civil service was “an idea for the history books”, wanted to change recruitment completely and proposed getting rid of permanent secretaries altogether in favour of chief policy officers separate from those who managed departments and oversaw implementation.

We need to bin some institutions and create others... We need to reorient Whitehall to think about to how to incentivise goals, not micro-manage method.

Cummings did not survive the rigours of the pandemic, and left Downing Street in November 2020. The task of reforming the civil service—because by no means all of his notions were wrong—remains unfinished. But the leadership election of summer 2022 did revive the idea that the Treasury was a fundamental obstacle to growth and prosperity. We will never know exactly what Liz Truss would have done in that regard, given her record-breakingly short premiership. It also seems unlikely that the current prime minister will make any radical changes, as he is a Treasury man through and through, and needs his chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, as a reassuring figure to soothe inflamed markets.

There we have it. The Treasury is the ultimate Whitehall survivor, so hardwired into the system that it has resisted even the express attempts of prime ministers to clip its wings. I hope this has been a helpful (if long) read: I will write a shorter essay very soon on how the task could be achieved in the circumstances of 2022. But any would-be reformer needs to know his history. As William Faulkner said, the past is never dead. It’s not even past.