General election '24: Northern Ireland (2)

A fascinating and volatile electoral landscape is developing as parties continue to unveil their strategies and candidates for July's contest

I suspect I will be writing a lot about Northern Ireland between now and the general election on Thursday 4 July. It is and remains a place dear to my heart and one I find endlessly fascinating, baffling and bemusing, but there is something more than that: I am starting to feel as if this election could be hugely significant and see a real shift in the political centre of gravity. What I can’t yet discern with any certainty is the outcome.

Last week I wrote about the background and context of the election in Northern Ireland: the re-establishment in February of the Northern Ireland Executive with Sinn Féin’s Michelle O’Neill as first minister and Emma Little-Pengelly of the Democratic Unionist Party as deputy first minister; divisions within the DUP and the resignation of its leader, Sir Jeffrey Donaldson; and political developments in the Republic of Ireland.

A few days ago, with some other observations on the course of the election campaign, I noted that Gavin Robinson had been confirmed as DUP leader and announced that his party would stand aside for other Unionist candidates in two constituencies, North Down and Fermanagh and South Tyrone.

On Friday 31 May, it was the turn of the hardline Traditional Unionist Voice party to announce its intentions. In March, the TUV leader, Jim Allister, used his party’s annual conference to unveil a “partnership” with Reform UK under which they would field “agreed candidates”. These have now been selected, and TUV/Reform UK will contest 13 of Northern Ireland’s 18 constituencies. Of the five seats in which it will not field a candidate, only one, Upper Bann, is currently held by a Unionist (Carla Lockhart of the DUP), and Allister argued that the “compelling reason” not to stand there was “not to assist a Sinn Féin victory”.

TUV/Reform will fight the following constituencies (current party in brackets):

South Antrim (DUP): Mel Lucas

East Antrim (DUP): Cllr Matthew Warwick

North Antrim (DUP): Jim Allister

East Belfast (DUP): John Ross

North Belfast (DUP): Cllr David Clarke

West Belfast (Sinn Féin): Ann McClure

South Belfast and Mid-Down (DUP): Dr Dan Boucher

Lagan Valley (DUP): Lorna Smyth

South Down (Sinn Féin): Jim Wells

East Londonderry (DUP): Cllr Allister Kyle

Mid-Ulster (Sinn Féin): Glenn Moore

Newry and Armagh (Sinn Féin): Cllr Keith Ratcliffe

Strangford (DUP): Cllr Ron McDowell

Let’s be clear about this: the chances of any of TUV’s candidates winning are extremely slender. The party did not field any candidates at the 2019 general election, and only one in 2017, Timothy Gaston in North Antrim. Only twice have TUV candidates even broken into double figures in terms of share of the vote: in 2015, Gaston won 15.7 per cent in North Antrim, still far behind winner Ian Paisley Jr of the DUP; and in 2010, Jim Allister, in the same seat, collected 16.8 per cent of the vote. It is TUV’s misfortune to put in its strongest showing in a constituency which is firmly in Paisley’s grip.

Like Reform UK in Great Britain, the only effect TUV is likely to have is to squeeze the support of parties broadly on its side. In East Belfast, Gavin Robinson’s majority over the Alliance Party is only 1,819; in South Antrim, Paul Girvan of the DUP only beat his Ulster Unionist Party challenger by 2,689; and in Lagan Valley, the circumstances of Sir Jeffrey Donaldson’s departure could put his 2019 majority of 6,499 over the Alliance Party at risk.

I would also suggest that none of the TUV candidates is of sufficient stature or eminence to make a disproportionate difference to the result. Allister himself is sui generis, eloquent, fiery, perpetually furious. But he is 71 years old, and Paisley has been at least sceptical about the DUP’s re-entry to the executive, which will blunt Allister’s best line of attack. If he wasn’t able to run Paisley very close in 2010, or Gaston in 2015 or 2017, it is hard to see how Allister might unseat him now.

Of the others, Jim Wells has the most extensive CV. He was a DUP member of the Northern Ireland Assembly for South Down from 1998 to 2022, a deputy speaker from 2006 to 2007 and minister of health, social services and public safety in the executive 2015-15. Having fallen out with the DUP, he was deselected in 2022, resigned from the party and endorsed TUV. Wells is an evangelical Christian with markedly conservative views on social issues, championing “traditional marriage, Young Earth creationism and its teaching in schools and opposing abortion. These will not hinder him within TUV’s traditional support base, but they are unlikely to give him a platform to reach beyond that base to attract new voters.

Elsewhere, the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) has confirmed that it will contest all 18 constituencies in Northern Ireland. It currently holds two seats, South Belfast and Foyle, though the incumbent for the latter, Colum Eastwood, has admitted he faces a “tough fight” against Sinn Féin to retain his seat. Meanwhile, Sinn Féin will field candidates in 14 seats: it is standing aside in East Belfast, South Belfast and Mid Down, Lagan Valley and North Down. The party’s director of elections, Conor Murphy, said he encouraged voters in those four constituencies to support:

progressive parties who will reject Tory cuts and Tory pacts. We need every constituency fighting back against that and we have decided to give the best chance in those four constituencies to those progressive and inclusive candidates who can win. It was not an easy decision for Sinn Féin to make but we believe it is in the best interests of society here in the north.

By “progressive parties” he essentially means the Alliance Party. My feeling is that the Alliance is going to be central not only to this election but to the fallout from it. I suspect the party may do well, perhaps winning three or four seats, which will all come at the expense of Unionist candidates and will therefore suit Sinn Féin very well. In the longer term, however, I think one of two things will have to happen. Either the Alliance will need to make it more explicit and more plausible that it does not need to have a settled view on the future of the Union and that there is a substantial section of the electorate which is much more interested in issues like the economy, public services, housing and law and order and will reward a party willing to focus on these rather than seeming obsessed with constitutional matters; or it will need to come to a more decided view on the Union, even if that view is only for the interim period and subject to wider public opinion.

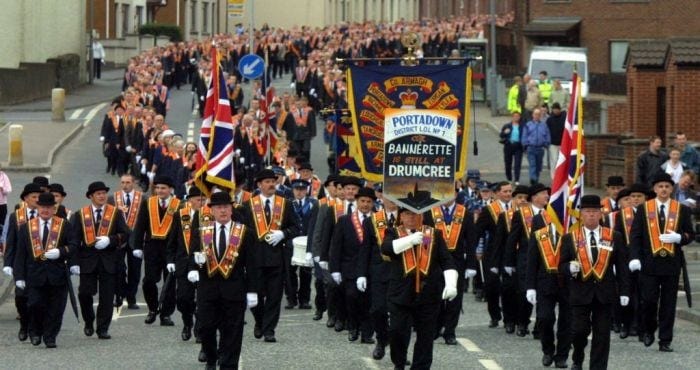

In any event, I will be fascinated to see how the individual races develop. Finally, it is worth bearing in mind—there is no reason this should occur to the casual reader—that the date of the general election, 4 July, is right in the middle of Northern Ireland’s marching season, when various Protestant, Unionist and Loyalist organisations hold parades to mark a range of events. The season at its broadest is roughly April to August but there will be parades to mark the anniversary of the Battle of the Somme on 1 July after which attention will turn to preparations for the Twelfth, the peak of the marching season as Unionists commemorate the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. So the election will not be taking place against a background of calm and quiet.