Farage eyes up DC: irregulars as ambassadors

The British government sometimes chooses non-diplomats for major ambassadorial roles, and there are lots of reasons: but Farage would go beyond that

Today an article in The Financial Times highlighted a difficult decision facing the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Dame Karen Pierce, the sometimes-unorthodox but popular and experienced UK ambassador to the United States, will turn 65 this autumn and reaches the end of her notionally four-year term next month. Although she is likely to stay in post until the end of the year, the FCDO needs to start the process of choosing a successor.

The timing is very awkward. We are expecting a general election, of course, and the indications at the moment are that the Conservatives will lose to Labour, so it may well be that Rishi Sunak and Lord Cameron of Chipping Norton oversee a process with the results of which Sir Keir Starmer and David Lammy have to live. Almost more importantly, if the decision is taken before 5 November, it will be made without knowing whether the new ambassador will be dealing with a re-elected President Joe Biden, or President Donald Trump back for a second stint (the first recidivist president since Grover Cleveland in 1893). Whatever you think of the “special relationship”, we can agree that the two men require different approaches.

I will be writing elsewhere about the potential candidates and how they might represent British foreign policy in America, but I wanted to look here at the idea some have proposed of looking beyond the Diplomatic Service for a candidate who is suited to the specific circumstances of time and place. Nigel Farage has of course weighed in, telling The Daily Telegraph that the new ambassador must effectively have Trump’s seal of approval: “whoever represents the UK needs to be someone that knows him and can get on with him. So if not me, then someone who fits that bill.”

Earlier this month, i News reported that Sir Liam Fox, former defence and international trade secretary, was being considered for the role. Although his “friends” denied he was interested and would “decline the job if offered as he wants to remain in the House of Commons”, Fox is 62, has been an MP for more than 30 years and is unlikely to find another major role domestically. However, Boris Johnson proposed him as an Atlanticist candidate for director-general of the World Trade Organization in 2020, and he progressed to the second round before being eliminated before the last stage. In 1997, he set up The Atlantic Bridge Research and Education Scheme (although it was dissolved in 2011 after criticism from the Charity Commission), which provided a forum for British and American conservatives, led a Conservative delegation to the Republican National Convention in 2008 and is UK chairman of Conservative Friends of America (recently renamed Transatlantic Bond).

It is not unknown for the Foreign Office to look beyond its own ranks for ambassadors and high commissioners. The current ambassador to Italy, Lord Llewellyn of Steep, was David Cameron’s chief of staff in Downing Street before being appointed ambassador to France in 2016, although he had a foreign affairs background working for Chris Patten as governor of Hong Kong (1992-97) and European commissioner for external relations (1999-2002) and Paddy Ashdown as high representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo (2002-05).

Senior political figures have taken major diplomatic roles in the recent past. Former chief secretary to the Treasury Paul Boateng was appointed high commissioner to South Africa by Tony Blair in 2005 and served until 2009, while there was a trilogy of political appointees as high commissioner in Canberra: former Conservative chief whip Alastair Goodlad (2000-05), ex-Scottish secretary Helen Liddell (2005-09) and former leader of the House of Lords Baroness Amos (2009-10).

There is nothing inherently wrong with sending party politicians to diplomatic posts. The United States regards this as a standard part of its diplomacy: former White House chief of staff and mayor of Chicago Rahm Emanuel is currently US ambassador to Japan, while Jack Lew, chief of staff then secretary of the Treasury, is ambassador to Israel. About a third of US envoys are “non-career ambassadors”, often close allies of the president or major donors to the political parties, and they occupy some of the the most senior diplomatic posts. Raymond Seitz, who was US ambassador in London from 1991 to 1994, was the first professional member of the Foreign Service to hold that post in modern history; five envoys (John Adams, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Martin Van Buren and James Buchanan) went on to be president, while the current ambassador, Jane Hartley, although she was ambassador to France from 2014 to 2017, worked for the Democratic National Committee (1974-77) and the White House Office of Public Liaison (1978-81) before enjoying a career as a broadcasting executive.

The British experience is also nuanced because, as well as ambassadors, the government for many years appointed imperial administrators who straddled the divide which we now thing of between politicians and civil servants. Most obviously, from 1833 to 1947, there was a governor-general of India (known as viceroy after 1858), a figure who in many ways had more individual authority than anyone else in the British government, and senior political and military figures were often chosen for the post. The last three viceroys were Lord Mountbatten, who was chief of combined operations then supreme allied commander South East Asia Command before appointment, Field Marshal Viscount Wavell, previously commander-in-chief India and commander-in-chief Middle East, and the Marquess of Linlithgow, who had been a junior minister in the Conservative governments from 1922 to 1924 and then chairman of the Unionist Party (the Conservative organisation in Scotland).

Prime ministers have reached for unorthodox appointments outside the mainstream when they have wanted to bypass the administrative norms or emphasise the importance of a particular relationship. Harold Wilson did this with the United Nations. When he first came to power, he turned to experienced colonial administrator Sir Hugh Foot, former governor of Jamaica (1951-57) and Cyprus (1957-60), and gave him an extraordinary tripartite role: he was elevated to the House of Lords as Lord Caradon, made a minister of state at the Foreign Office and named UK permanent representative to the United Nations, retaining the roles until Wilson was defeated in 1970.

It was a strange mixture of duties, although very much in tune with the radical spirit which Harold Wilson projected more than he felt. The minister certainly knew the landscape of diplomacy. One obituary described Caradon as “as at ease and in command of his duties as a politician… strikingly eloquent and forceful both in oratory and debate”, making him a “powerful champion who never lacked the courage of his convictions”. And it was a time at which many of the problems with which Britain had to contend at the United Nations stemmed from the process of decolonisation, especially the crisis in Southern Rhodesia (which after the transformation of Northern Rhodesia into an independent Zambia in 1964 styled itself simply “Rhodesia”).

I touched on Caradon’s tenure some time ago when discussing Lord Frost. It was not a disaster, by any means: indeed, Caradon was a good minister and a good permanent representative who certainly was in sympathy with his political masters-cum-colleagues. But it worked for personal rather than institutional reasons. Douglas Hurd had worked at the UK mission in New York under Caradon, and expressed doubt about the arrangement in his maiden speech in the House of Commons in 1974:

I wonder whether that experiment was a success. It seemed to me that Lord Caradon was constantly arousing, through no fault of his own, expectations which the Government at home were not always able to fulfil.

It also meant, of course, that Caradon left office when Wilson’s government was defeated in 1970. This is an issue which faces the United States: if many of your senior diplomats are polical appointees, they are likely to be replaced whenever a new party takes office. Raymond Seitz, the ambassador in London mentioned above, was additionally rare because, although he had been appointed by George H.W. Bush, he remained in post when Bill Clinton became president in 1993, and only gave up office 16 months into Clinton’s first term.

(Foot was no stranger to politics: his brother Michael was a Labour MP from 1945 to 1955 and 1960 to 1992, and led the Labour Party 1980-83. Another brother Dingle was a Liberal MP from 1931 to 1945 then a Labour MP 1957 to 1970, and solicitor general under Wilson 1964-67. Yet another brother, John, rated by Michael as “the ablest member of the family”, was appointed a Liberal peer in 1967. Their father, Isaac Foot, was Liberal MP for Bodmin 1922-24 and 1929-35, and served as secretary for mines in the National Government in 1931-32. Caradon’s son Paul Foot was a renowned investigative journalist and author.)

Harold Wilson was clearly struck by the idea of a politician representing Britain at the UN. When he returned to Downing Street in March 1974, he recalled Sir Donald Maitland, Edward Heath’s press secretary who had been in New York less than a year, and instead selected as permanent representative Ivor Richard, a former Labour MP. Richard—who would eventually be Tony Blair’s first leader of the House of Lords—had been MP for Barons Court since 1964 and a defence minister in 1969-70, but when his constituency was abolished by the Boundary Commission, he landed as candidate in Blyth in Northumberland, where the sitting Member, Eddie Milne, had been deselected. Richard, a clever but sometimes ponderous Welsh lawyer with no local connections, lost to Milne, standing as an independent, by more than 6,000 votes.

Richard was in some ways a man too able to be used by the new government. Praised in tributes after his death for “his clarity of thought [and] his skill as a communicator”, he was more than able to master the subjects placed before him: Rhodesia (still) and the conflict in the Middle East. A profile in The New York Times when he left the position in 1979 was affectionate. He “smokes incessantly—Cuban cigars, pipe, cigarillos or cigarettes, it does not seem to matter”, the paper noted, and summed up his tenure, “uncommonly long for a diplomat”, as:

the crises over Cyprus, the Middle East or southern Africa, the predawn telephone: summonses to emergency meetings, the round‐the-clock negotiations, the strategy sessions, which were secret and often exciting, or the formal sessions, which were public and often dull.

His style had often been unusually combative. He became embroiled in a war of words with his American counterpart, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, over Resolution 3379, which declared “Zionism is a form of racism”. When Moynihan criticised the document, Richard accused him of behaving “like the Wyatt Earp of international politics”, and compared Moynihan’s approach to developing countries as being like “Lear raging amidst the storm on the blasted heath” and “Savonarola in the role of an avenging angel preaching retribution and revenge”. Yet in a 1976 profile in TIME, an aide said “His method, which befits the good barrister he is, is to persuade rather than dictate”, while a senior FCO official remarked, “Had he become a member of the diplomatic service instead of a lawyer and politician, he would have risen to the top of the Foreign Office”.

Several “political” ambassadors were appointed during the Second World War, when the boundary between politicians and administrators was blurred as never before or since: in 1942, the permanent secretary at the War Office, Sir James Grigg, had the unenviable task of telling his minister, David Margesson, that he was being dismissed and that he, Grigg, was replacing him, in what remains a unique event in British administrative history. Churchill sent Labour MP Sir Stafford Cripps to be ambassador to the Soviet Union, on the grounds that his Marxisy sympathies would give him a rapport with Stalin, appointed Ronald Cross, former minister of shipping, as high commissioner to Australia, and made Lord Harlech, ex-colonial secretary, high commissioner to South Africa. Duff Cooper, who had resigned from Chamberlain’s cabinet in protest at the Munich Agreement, became British representative to General Charles de Gaulle’s French Committee of National Liberation in 1943 and then ambassador to France in November 1944. Unusually, he was not replaced immediately by the incoming Labour government in 1945 but remained ambassador until 1947.

The post of British ambassador to the United States, which is the lynchpin of the UK’s most important bilateral relationship, has been occupied by “political” appointees perhaps more often than any other. In that respect, Nigel Farage’s candidacy, or that of Liam Fox, is not revolutionary. Indeed, it goes back a very long way.

In 1906, the foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, recalled the ambassador, Sir Mortimer Durand, on the grounds that he had lost the confidence of President Theodore Roosevelt and his secretary of state, Elihu Root. Roosevelt preferred dealing with Cecil Spring-Rice, best man at his second wedding in 1886 and sent to Washington as a special representative in 1906, and Durand had enemies in London: he had previously been in the Indian Civil Service and was regarded as an intruder in the world of high diplomacy.

To replace Durand, Grey—who would himself spend five short months as ambassador in Washington in 1919-20—and the prime minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, looked round the cabinet table. James Bryce, a 68-year-old Ulsterman, had practised as a barrister for a while after an education which had taken in the University of Glasgow, Heidelberg and Trinity College, Oxford, but in 1870, only in his thirties, he had been appointed regius professor of civil law at Oxford, one of the university’s oldest chairs. He combined the role with active Liberal politics, becoming MP for Tower Hamlets in 1880, relocating to South Aberdeen in 1885. In 1892, he joined Gladstone’s last cabinet, as chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and served as president of the Board of Trade under Lord Rosebery (1894-95). When the Liberals returned to power in 1905, he became chief secretary for Ireland, effectively head of the government in Dublin but sitting in cabinet in London.

Bryce was a radical, but by the mid-1900s, wary of appeasing the threat of socialism, he opposed many of social reforms on which the new government was set, including the Trade Disputes Act 1906 and old-age pensions (and he would later oppose the “People’s Budget” of 1909/10). However, his fame and erudition had been cemented for a transatlantic audience when in 1888 he had written The American Commonwealth, a brilliant political, constitutional and legal analysis of the United States, and he had developed close friendships with Charles Eliot, president of Harvard from 1869 to 1909, Lawrence Lowell, the professor of government who would succeed Eliot, and James B. Angell, president of the University of Michigan.

This seemed to present an elegant solution to several problems. Sending Bryce to Washington as ambassador removed him from cabinet without demotion or dishonour, provided the British embassy there with an occupant of existing fame and weight and hardly looked as if Durand had been thrown over for petty reasons. When the Encyclopaedia Britannica reviewed Bryce’s appointment for its 12th edition in 1922 (he died in January that year), it was gushing.

The United States had been in the habit of sending, as minister or ambassador to the Court of St James’s, one of its leading citizens: a statesman, a man of letters, or a lawyer whose name and reputation were already well known in Great Britain. For the first time Great Britain responded in kind. Bryce, already favourably regarded in America as the author The American Commonwealth, made himself thoroughly at home in the country; and, after the fashion of American ministers or ambassadors in England, he took up with eagerness and success the rôle of public orator on matters outside party politics, so far as his diplomatic duties permitted.

Bryce retired in 1913, and Spring-Rice eventually became ambassador, though by then his great friend Roosevelt had left the White House and failed in his attempt at re-election as a Progressive in 1912. After him, though, came a quick-fire series of political appointees: the Earl of Reading (1918-19), the former Liberal attorney general who managed to hold the job in tandem with being lord chief justice; Edward Grey, mentioned above, by then Viscount Grey of Fallodon, only 57 but almost entirely blind and unable even to engineer a meeting with President Woodrow Wilson, who suffered a debilitating stroke a month after Grey’s appointment; and then Sir Auckland Geddes, Unionist MP for Basingstoke, who had been president of the Local Government Board (1918-19), minister of reconstruction (1919) and president of the Board of Trade (1919-20).

Politicians have been sent to Washington at other times of crisis. The 11th Marquess of Lothian, a clever but self-absorbed man whose nickname at Oxford had been “Narcissus”, had cut his teeth as an imperial administrator in South Africa as part of “Milner’s Kindergarten”: this was a claque of young reformist-minded disciples of Alfred Milner, Anglo-German, classical scholar at Balliol College, Oxford, under Benjamin Jowitt, and governor of the Transvaal and Orange River Colony from 1902 to 1905. Lothian was a minister at the beginning of the National Government in 1931-32, then spent the mid-1930s as an apologist for Nazi Germany, uttering the famous judgement of Hitler’s re-occupation of the Rhineland in 1936 that the German s were only going into “their own back garden”. He became disillusioned with Nazism rather late, in 1938, after reading Mein Kampf, and only truly saw reality in March 1939. When, that month, German forces occupied Czechoslovakia, Lothian write to a friend:

Up until then it was possible to believe that Germany was only concerned with recovery of what might be called the normal rights of a great power, but it now seems clear that Hitler is in effect a fanatical gangster who will stop at nothing to beat down all possibility of resistance anywhere to his will.

Better late than never. On the day that Germany invaded Poland, 1 September 1939, he arrived at the White House to present his credentials as ambassador to Washington, Sir Ronald Lindsay having retired in the summer after nine years in post. His role was clear, to seek as much support as possible from America in the coming war—Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September—and he set about it in a highly visible and populist manner which alarmed the mandarinate in London. In the words of one American historian, Lothian, whose Anglo-Norman family had settled in Ayrshire in the 12th century and whose title dated from 1701:

grasped that Americans were much taken with bluebloods exhibiting a just-plain-folks demeanor. Thus, he wore a battered gray fedora, drove his own car, and bought his own train tickets when travelling in the United States.

He liked to show visitors to the embassy the enormous portrait of George III and describe him as “the founder of the American republic”. But he was shrewd too, understanding that Americans, naturally inclined towards isolationism, should not be hectored. He wrote to Lord Halifax, the foreign secretary, at the beginning of 1940:

We have to prove to the USA, which includes public opinion as well as the administration that any action we are taking is really necessary for the winning of the war… the one fatal thing is for us to offer the United States advice as to what she ought to do. We have never listened to the advice of foreigners. Nor will the Americans.

Lothian was winning. The US ambassador in London, the isolationist and anti-British Joseph Kennedy, was firm in his belief that Franklin Roosevelt, approaching the end of his second term as president and considering the unprecedented step of seeking a third term, was colluding with Winston Churchill (who had become prime minister in May 1940) and “the Jews” to drag American into the European war. But that year, the head of the State Department’s European division, Jay Pierrepoint Moffat, remarked, “If Kennedy says something is black and Lothian says it is white, we believe Lord Lothian”.

It was not to last. Along with his friend Nancy Astor, he had converted to the Church of Christ, Scientist, in 1914. At the end of 1940, he developed a kidney infection but refused treatment on religious grounds, and died of uremic poisoning on 11 December. Churchill said it was a “monstrous thing” that the ambassador had denied himself medical attention, while Halifax, not an unkind man but the highest of High Anglicans, described him as “another victim for Christian Science”.

With the Japanese strike on Pearl Harbor still a year away, Lothian’s mission was unfinished. Churchill’s first choice to replace him was the former prime minister David Lloyd George, possibly the only man from whose spell he never escaped. Still MP for Carnarvon Boroughs, the Welshman thought Britain’s chances of success in the conflict were poor, though still saw a role for himself at the head of national affairs. But Washington did not appeal, and he pleaded his age (he was 77). The prime minister also considered the leader of the Liberal Party, Sir Archibald Sinclair, then at the Air Ministry, and the dry, waspish Bobbety Cranborne, secretary of state for Dominion affairs. Eventually, however, he turned to the foreign secretary himself, Lord Halifax.

Edward Halifax wanted few things less than to be ambassador to the United States. He was approaching 60, and, while he had effectively ruled himself out of being prime minister when Churchill had succeed Chamberlain in May that year, it is not at all certain he thought that was the only time the position might come his way. He regarded the job as “an odious thought” and tried to persuade Anthony Eden to take it, while also suggesting Lord Woolton, the minister of food.

Halifax was not a like-for-like replacement for Lothian in any sense except in his aristocracy: he was stiff, sometimes gloomy, devoted to the Church of England and fox-hunting. Rab Butler, his junior minister at the Foreign Office, described him as “this strange and imposing figure—half unworldly saint, half cunning politician”. He had a heavy kind of authority, reinforced by being 6’5”, but he had no affinity at all with America.

On the other hand, his departure recommended itself to Churchill. Neville Chamberlain had died the previous month, John Simon had been shunted out of the front line to be lord chancellor and Samuel Hoare was by then ambassador to Spain, so Halifax was the last of the senior cabinet figures associated, not wholly fairly, with appeasement. His appointment to Washington would allow Churchill to make Eden foreign secretary again—he had held the post from 1935 to 1938—and exercise a degree of supervision on the younger man.

Finally, while it seems absurd now, knowing how events transpired, Churchill had reason to fear Halifax. The prime minister had only taken over the leadership of the Conservative Party after Chamberlain’s death, and his relationship with it was uneasy: he had been a rebel more or less from the right throughout the 1930s, but it was never forgotten that from 1904 to 1924 he had been a Liberal, and his sense of loyalty to any party was very slight. Nearly 400 of the 615 MPs were Conservatives, their crushing dominance only thinly veiled by the government’s “National” label, and Churchill knew that the war was going badly and could get worse. If his appeal palled, Conservatives had a ready champion in Halifax.

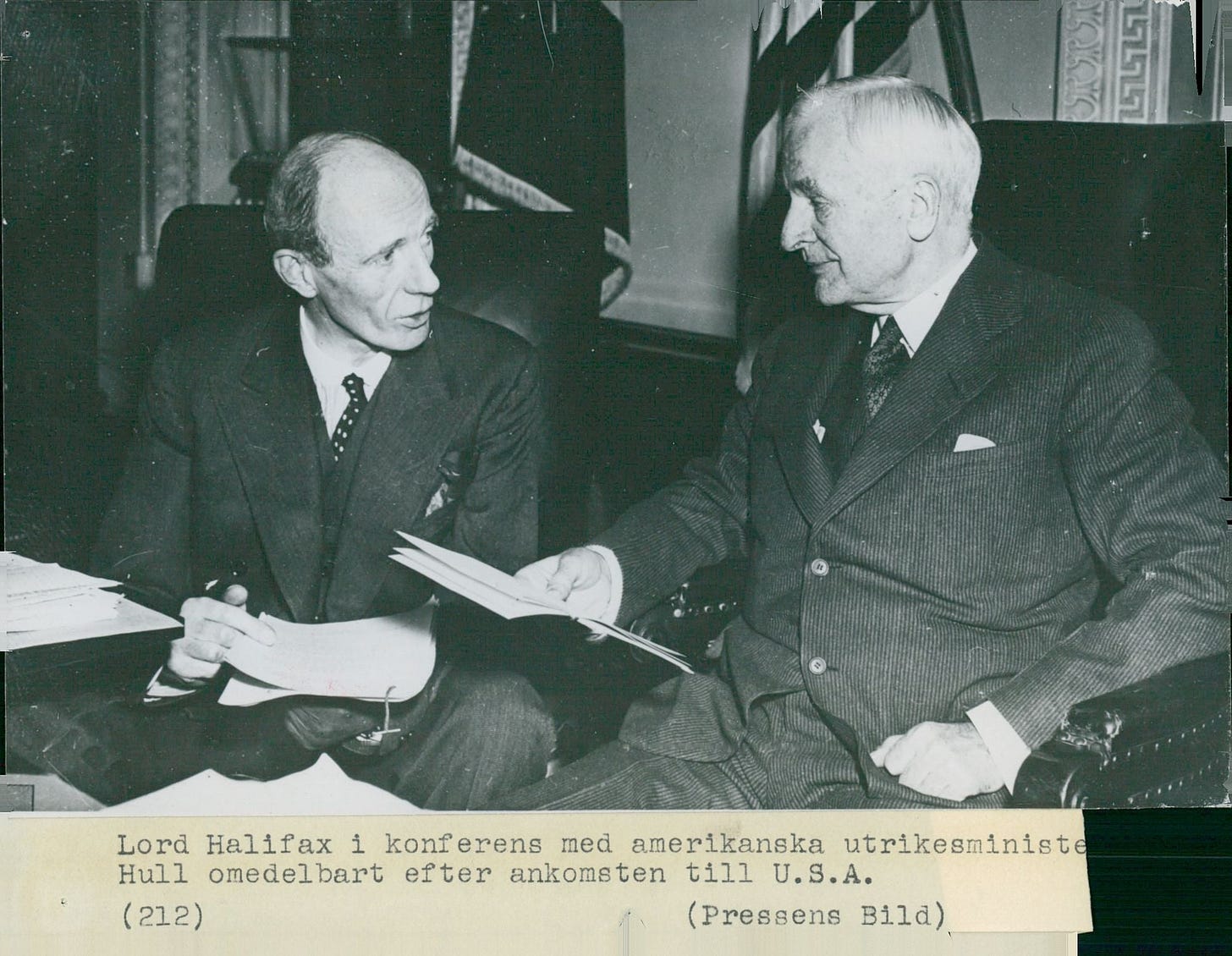

If Halifax was sent to Washington largely for negative reasons, the new envoy eventually found his feet. There were gaffes and missteps in his first months, but he was clever, diligent and honest. In any event, the role of ambassador was changing. Churchill was able to visit the United States and travel elsewhere more easily than previous premiers—he and FDR met 11 times—and spoke frequently to Roosevelt on the telephone. Between 1939 and 1945, they exchanged 1,700 letters and telegrams, and the prime minister estimated that during the war he and the president had 120 days of close contact. Once America had joined the war in 1941, more and more of the bilateral relationship concerned military affairs, and these were generally handled by the Combined Chiefs of Staff. On a day-to-day basis, this meant the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington, headed by Field Marshal Sir John Dill, formerly chief of the Imperial General Staff (1940-41) and also sent to America by Churchill to get him out of his role in London.

Halifax tired of Washington. In October 1942 his middle son, Major Peter Wood, was killed in action serving with the Royal Armoured Corps in Egypt, and in December, his younger son, Lieutenant Richard Wood, lost both legs when they were crushed by a bomb which nevertheless did not explode. In March 1943, he asked Eden to be relieved, but was refused, agreeing in July 1945 to stay on when Labour came to power and eventually stepped down in May 1946.

The Washington embassy has attracted other “irregulars” since the end of the Second World War. David Ormsby-Gore, a Foreign Office minister from 1956 to 1961, became ambassador in 1961. He had a warm friendship with Jack and Bobby Kennedy, to whom he was distantly related, and in 1968 would propose to Jacqueline Kennedy (she was touched but declined). In 1969, Harold Wilson chose John Freeman, a former Labour MP who had resigned from the Attlee government with him in 1951 and had been high commissioner to India from 1965 to 1968. Although Wilson had sent Freeman in anticipation of a Democratic candidate winning that year’s presidential election, the new ambassador forged a good relationship with Richard Nixon and his national security advisor, Dr Henry Kissinger. But in 1971 Freeman became chairman of London Weekend Television.

Edward Heath did not revert to a mainstream diplomat, though he did not choose a politician. To succeed Freeman, he chose the Earl of Cromer, who had been governor of the Bank of England from 1961 to 1966 but had found Wilson a difficult prime minister and had not sought a second term. He had been economic minister in the Washington embassy 1959-61, also serving as the UK’s director of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, but began his career in the family bank, Barings. Heath chose Cromer as ambassador, according to his obituary, “to use his banking background to explain the economic reasons behind Britain’s push for entry into the European Common Market to the US government.”

It was a rare nod to the Special Relationship by Heath, who tended to see Britain’s links with the United States and Europe as a zero-sum game. Kissinger claimed that Heath actively rejected a close relationship with President Nixon, leaving America’s sometimes thin-skinned leader feeling like “a jilted lover”. But the channels of communication between London and Washington were diffuse. Nixon distrusted the State Department and despised the CIA, relying almost solely on Kissinger but accepting a degree of contact with Heath’s cabinet secretary, Burke Trend. The foreign secretary, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, was experienced and respected but Heath preferred to deal with the most pressing foreign policy issues himself.

Cromer left Washington in 1974. He was succeeded by Sir Peter Ramsbotham, a career diplomat, one of the last diplomatic appointments Heath made before he left Downing Street in March 1974. Ramsbotham was highly regarded and especially respected for his grasp of the economics of oil, and he found himself able to strike a cordial relationship with Jimmy Carter, the Democratic governor of Georgia who beat Gerald Ford for the presidency in 1976. He would be the first ambassador invited to the Carter White House, but in May 1977, he was recalled and the last “irregular” to hold the job to date was installed.

Peter Jay was 40 years old, had been a civil servant at HM Treasury from 1964 to 1967 but had resigned during the crisis over devaluation, then had spent 10 years as economics editor of The Times. He was also the son of a former Labour cabinet minister (Douglas Jay, president of the Board of Trade 1964-67) and son-in-law of James Callaghan, who by 1977 was prime minister. And the foreign secretary since February 1977, who was the driving force behind the appointment, was David Owen, a close friend of Jay’s.

It was not that Jay lacked ability or was unqualified, though at 40 he was young to be one of Britain’s most senior ambassadors. Appointing the prime minister’s son-in-law, however, was always going to be controversial, and the Foreign Office made matters worse by suggesting, inaccurately, that Ramsbotham was old-fashioned and snobbish. Jay recounts that the permanent secretary, Sir Michael Palliser, was quite open that he had advised strongly against the appointment but that they “both tried extremely hard to make the relationship work despite the controversial nature of my appointment”.

Jay was realistic enough to see that the defeat of his father-in-law’s government at the general election in May 1979 made his position difficult. He told Bryan Cartledge, the prime minister’s private secretary for foreign affairs, that he placed his resignation in Margaret Thatcher’s hands, but was not forcing the issue. The response came through, “she says you’re doing a fine job, why don’t you carry on?” However, the new prime minister was also struggling to find a role for her Conservative predecessor. Heath seems to have expected to be made foreign secretary, the role he had given to his own predecessor, Alec Home, but that was never going to happen.

Thatcher therefore offered Heath the position of ambassador to Washington. It was not an outrageously lowly suggestion, even for a former prime minister, but Heath refused without hesitation, and that was quickly public knowledge. Indeed, the text of his response was printed in The Washington Post.

Dear Margaret, thank your for your note. As I have said, I do wish to stay in the Commons. I am sure you will be able to find somebody to do the job well. Yours, Ted.

Lord Carrington, whom Thatcher had appointed foreign secretary, had supported the offer but reflected afterwards, “I thought a little sop would be a good idea, but it was a thoroughly bad idea”. Was it a formality? It was followed by an offer of support to become secretary general of NATO when the post next fell vacant—in which Heath had no more interest than the Washington job—so it may have been sincerely meant. Thatcher may have felt some of the same motivation that Churchill did when he asked Halifax to be ambassador, that it would take Heath off the domestic political scene. But I doubt she minded much either way.

However, Jay was on the way out. Within weeks of Thatcher’s relayed message of support, Carrington wrote a letter to Jay:

which said (he was always very friendly—a very nice man) the Press seem to have got hold of the idea that we’re going to make a change in Washington, he said, so I suppose we’d better. And I’ve persuaded Nico Henderson to come out of retirement.

Henderson had retired as ambassador to France on his 60th birthday on 1 April 1979, so his “retirement” had not lasted long. The reversion to a professional diplomat, albeit one dragged back from his ease, proved a notable success when in 1982 the Falklands War broke out. Henderson acted as an eloquent advocate of the British case in a sceptical America and found an easy and warm relationship with Ronald Reagan, who had become president in January 1981.

There are other “irregulars” I could mention. Peter Carrington himself was high commissioner in Canberra from 1956 to 1959, appointed at only 37 by Sir Anthony Eden; The Daily Telegraph called his “three years in Australia… some of the most successful of his career” and he was popular with the long-serving prime minister, Robert Menzies (1939-41, 1949-66). Christopher Soames, Churchill’s son-in-law and a Conservative cabinet minister under Harold Macmillan and Alec Douglas-Home, having lost his seat at Bedford in the 1966 general election, was appointed ambassador to France by Harold Wilson in 1968. He was what one historian called a “single issue ambassador”, chosen to use his reputation and connections to persuade the French government to drop its opposition to Britain’s application to the European Economic Community.

If there is a lesson is all of this, it is that appointing “political” outsiders to diplomatic posts is neither especially unusual, particularly in the case of the Washington embassy, nor necessarily damaging or unwise. Sometimes these positions are used negatively, to eliminate a rival like Halifax, or, more neutrally, to reward allies, like Llewellyn. More often, however, non-diplomats have been appointed to tackle major challenges. Whether it is Cromer being sent to Washington to explain the UK’s European policy or Lothian acting as a cheerleader for America becoming more involved in the war in Europe, prime ministers and governments have decided that it is necessary to go beyond the usual pool of candidates, and be seen to do so.

Making Farage ambassador to the United States—which, for clarity, I don’t think will happen—would be most akin to the appointment or Ormsby-Gore to penetrate the Kennedy White House. The difference, on which I may dwell elsewhere, is that Ormsby-Gore was a former minister and MP, and, although he had a strong bond with the Kennedy family, was never regarded as anything other than an advocate for British interests. Farage is essentially an ideological ally of Trump, an acolyte of the personality cult. That is something very different, and very much more worrying.