Don't lie to yourself: why commentators have to be honest

The example of Enoch Powell's approach to India shows how painful intellectual honesty can be and we have sometimes neglected it looking at Donald Trump

It’s either a source of exasperation or an unending wellspring of delight for my readers that I have interests which are, as I think of it, promiscuous. I want to know about more subjects than I will ever master, and I am forever thinking “Must read up on this!”, sometimes making an Amazon raid because it will surely force me to learn about the Order of Assassins or London as a centre for money-laundering or the titan of British design. So I find myself writing about day-to-day domestic politics, of course, because that has been my immediate obsession for 30 years and more; about Parliament and the constitution, because in a small way I used to operate it as a clerk in the House of Commons; about communications, public relations and reputation management, because I worked in that field for a time too; and about foreign policy, defence and national security, because they have always fascinated me, I have immersed myself in the subjects professionally from time to time and I know a smattering of very eminent people in those fields whom I find fascinating.

Add to this an abiding interest in culture in all its forms—I co-founded and co-manage a digital-first culture journal in which we try to range widely—and a desire to explore theories and hunches about film and theatre and music and television, and how they affect and are affected by society and politics and history. And I still keep a foot in the camp of my original academic bailiwick, which is sixteenth-century history, especially political and religious (see this and this and this).

This is a reasonably wide spectrum, though, I hope, not an unmanageable one. Sometimes, though, you find yourself returning by different routes to the same destination, dwelling on a recurring theme. You find a golden thread, if you will (though the phrase makes me think before anything else of an excellent but perhaps not hugely au courant 1983 volume of Sir John Mortimer’s legendary Rumpole chronicles).

The theme which keeps dragging me back at the moment is intellectual honesty: the idea that if you are any kind of analyst or commentator or public thinker in any discipline, you have to proceed from a basis of acknowledging the known facts rather than ignoring them or smothering them with the more comforting contours of how you would like things to be.

This is hard. My friends and my bank manager will tell you that I don’t always excel at facing facts and taking necessary action, but in the public sphere it is absolutely essential. Politicians who propose ideas or actions which are unmoored from reality, which try to ignore what is true and real and manifest, are fooling themselves, and therefore seeking to fool us. At best they should be pitied and comforted, and at worst they have earned excoriation and contempt. But it is important to cut at least a little slack to begin with, because, as I say, intellectual honesty is hard.

One of the starkest examples of this in public life is Enoch Powell’s relationship with India. One of only two men to go from private to brigadier during the Second World War—he was plucked from the ranks for officer training when an inspecting brigadier asked Lance-Corporal Powell a question and was given an ancient Greek proverb as a response—Powell was a brilliant intelligence officer but, to his great and lasting regret, never saw combat. In August 1943, convinced that, after the Battle of el-Alamein the war in Europe was effectively won and that the decisive struggle was now in the Far East, he obtained a transfer to the Directorate of Military Intelligence of the British Indian Army as a lieutenant-colonel. He bought every book he could find on India and devoured his hoard, writing home to his parents that he “soaked up India like a sponge soaks up water”.

It is fair, I think, to say that Powell fell in love with India; indeed, he would himself talk of it as a “love affair”. He was a man of deep and powerful passions, usually but barely held in check, and there was something about the place that seized his spirit (I would say “soul”, but at that point he was still a Nietzsche-influenced atheist, only embracing the Church of England in 1949). More specifically, he fell in love with British India. In an article entitled “Passage to England” in The Birmingham Post in 1959, he wrote, just a dozen years after Partition:

To be one of the diminishing number of those who actually witnessed the phenomenon of British India is like belonging to a dying race which cannot pass its secrets on.

It was a very Powellian way of putting it: gloomy, doom-laded, grim-visag’d. You can can hear his flat West Midlands register very clearly.

For a while, though, India was Powell’s world. On arrival in Delhi in 1943, he became secretary to the Joint Intelligence Committee (South-East Asia and India Command). In March 1944, he was promoted to full colonel and appointed assistant director of military intelligence, and in October he was promoted again to brigadier to serve as one of the three army members of the Committee on the Reorganization of the Army and Air Forces in India, chaired by Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Willcox, formerly GOC, Central Command. (The other members were Brigadier Gordon Thompson and Brigadier K.M. Cariappa, later commander-in-chief of the Indian Army.) The resulting 470-page report was almost all Powell’s work.

India was also the focus of Powell’s professional ambitions. He started learning Urdu when he arrived in Delhi, and achieved interpretation level in it and Hindi (he was a formidable and instinctive linguist, speaking at least eight languages fluently by the time he died in 1998). Although he turned down a regular commission in the Indian Army, and the position of assistant commandant of an officer training academy, he had in fact set his sights higher: his ambition was to be viceroy of India, head of the British government in Delhi.

What was it that captivated Powell in India? He explained it in characteristic terms when interviewed for the Imperial War Museum’s archives in 1987.

The unconstrained wonder of it, this unbelievable phenomenon of a vast continent with tumultuous history, and the marvellous variety of languages and people cohering apparently effortlessly, by reason of the improbably connection with it of a few thousand people from a group of islands in the North Atlantic. This was—is—one of the wonders of the world… it was like being with Alexander in his army when he travelled from Greece to India, a miracle happened and the miracle was still continuing to happen.

Hardly for the first time, Powell was a man out of time. He recognised this, in some ways, and would say of his time in the dimming days of the Raj, “If I’d have gone there a hundred years earlier, I would have left my bones there”.

The viceroyalty seems in hindsight a quixotic desire, knowing that India would be partitioned into independent states in August 1947; perhaps it was so at the time. But Powell was in deadly earnest, and it was in pursuit of this ambition that he left the army later in 1945 and decided to seek preferment at Westminster. As he wrote to a friend:

I thought of how Burke had said 160 years earlier that the keys of India were not in Calcutta, not in Delhi, they were in that box—the Despatch Box at the House of Commons. I decided at that time that I must go there.

He would later say that the realisation had come to him, appropriately, at the break of the monsoon in 1944.

One day, when the monsoon broke in Delhi, in June 1944, I suddenly said to myself ‘You are going to survive—there will be a time when you will not be in uniform. Painful though it may be, you have got to face it. There will be a lifetime for you and a lifetime not as a soldier.’ This was the opening of the door from one mental room to another, and there was the answer of course: you will go into politics in England.

Powell had voted Labour in the 1945 general election, believing the Conservative Party should be punished for the ignominy of the Munich Agreement of 1938, but he was by inclination and instinct a Tory. He had been, like, he said, many of his generation, politicised by war, explaining:

But for the war we wouldn’t have thought of politics. We were surprised to find ourselves alive. We weren’t interested in a military career, so we descended to politics. The party was so broken in 1945, they were nothing loath to accept help. In 1945 we were a defeated army.

He found a position first in the Conservative Parliamentary Secretariat and then, famously, in the mainstream of the Conservative Research Department. There he worked alongside future titans of the party like Iain Macleod and Reginald Maudling, under the chairmanship of Rab Butler, later chancellor of the Exchequer, home secretary and de facto deputy prime minister. He arrived to be interviewed by David Clarke, director of the CRD, early in 1946 in his brigadier’s uniform; Clarke recalled later that he “was never to forget the experience of vetting an immaculately dressed Brigadier for a job that largely involved taking minutes at committee meetings and preparing briefs for debates and speeches”.

Appropriately for one of his experience, Powell dealt with most defence-related matters which came to the CRD, but he also worked hard on apparently humdrum issues like housing and local government finance, producing more than 40 memoranda on what became the Town and Country Planning Act 1947. But in 1946, tellingly, he had drafted (on his own initiative) a 25,000-word memorandum on a renewed commitment to India which would involve the enormously costly reorganisation of agriculture and industry. Butler agreed to present the paper to Winston Churchill, then leader of the opposition and into his 70s, “who seemed distressed and asked me if I thought Powell was ‘all right’. I said I was sure he was, but explained that he was very determined in these matters.”

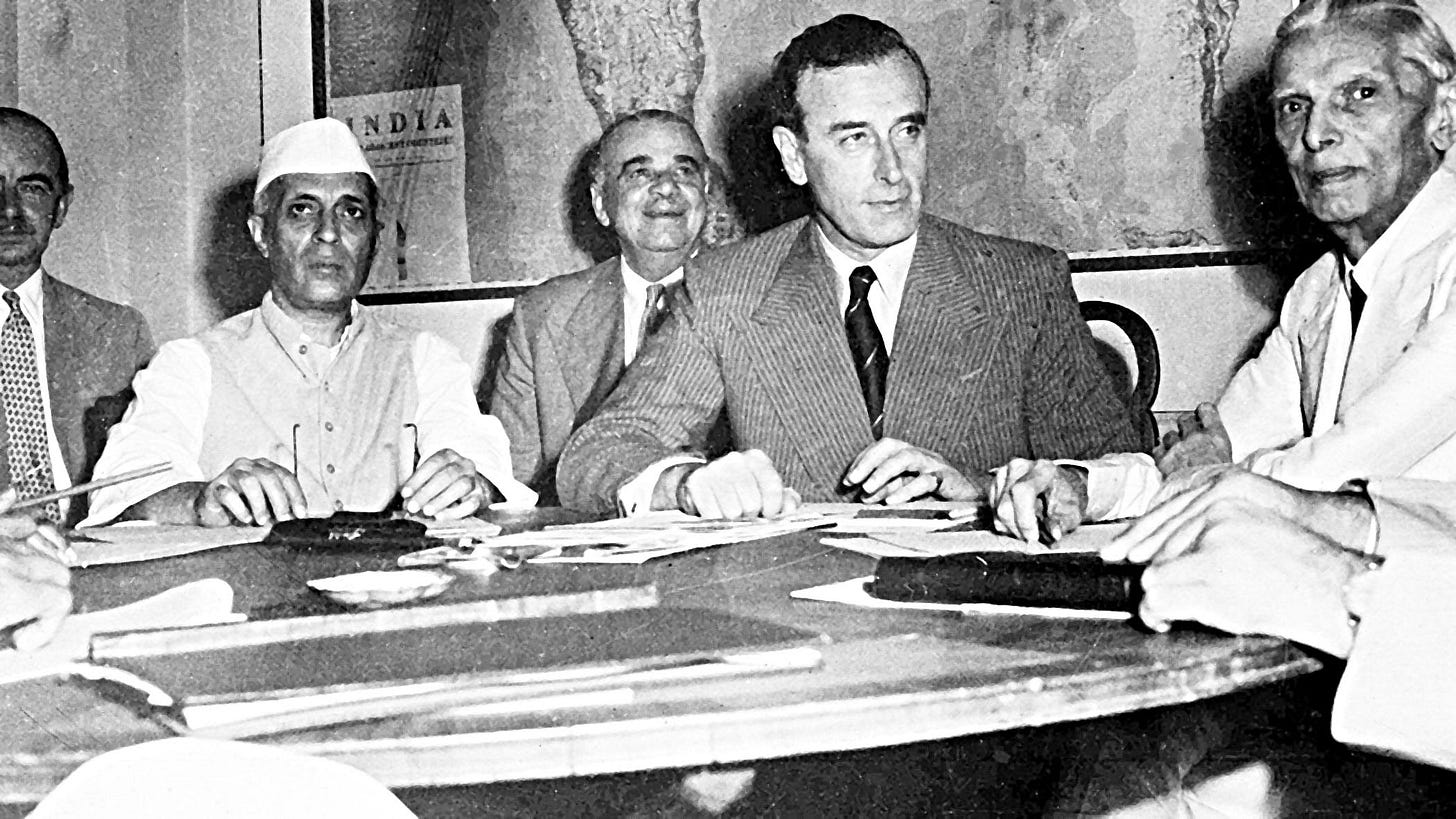

Everything changed in one day. On 20 February 1947, the prime minister, Clement Attlee, made a statement on India to the House of Commons. Noting that it had “long been the policy of successive British Governments to work towards the realisation of self-government in India”, he announced that Field Marshal Viscount Wavell was stepping down as viceroy and would be succeeded by Rear Admiral Viscount Mountbatten of Burma. The crux of the statement was this.

His Majesty’s Government wish to make it clear that it is their definite intention to take the necessary steps to effect the transference of power into responsible Indian hands by a date not later than June, 1948.

In fact matters moved much more quickly than that. The government was under pressure from Indian leaders to hand over power, and the financial benefits of demobilisation were enormous to a cash-strapped nation. In June, Mountbatten announced a plan for independence based on the principles that there would be two separate successor states, India and Pakistan (East and West), both of which would have dominion status, and which would have full autonomy. On 18 July, the Indian Independence Act 1947 received Royal Assent, and it came into effect on 15 August. It was not quite six months since Attlee had made his statement to the Commons.

The event was shattering for Powell, who walked the streets of London all night. “One’s world had been altered,” he wrote. As Dr Ian Patel has expressed it:

The loss of India for Powell meant that the bonds of hierarchy, military authority and allegiance to the Crown in the colonies—the tissue of his experience of empire—were lost irretrievably.

This is the heart of the matter, the pivot of intellectual honesty. Once Powell accepted, however distraughtly, that India was lost to the empire, he did not, like many colleagues in the Conservative Party and on the right of politics in general, try to prolong the appearance of imperial prestige and influence, and he had little time for the grand rhetoric with which the Commonwealth was and is garlanded. Rather, he believed, as countries left the empire, they assumed responsibility for their own affairs and ceased to be Britain’s concern, or central to Britain’s national interest.

It was in Powell’s nature that, once a decision had been made, it was absolute. As Dr Victoria Honeyman of the University of Leeds put it, he was:

an intellectual in the true sense of the word. He would follow the logic of an intellectual argument to its conclusion, regardless of how unpalatable that conclusion was, and then present it and often expect others to appreciate his process.

Once an arch-imperialist, Powell became a radical nationalist, in some senses of the word: he refocused his conception of identity and self on the United Kingdom, and often, really, on England, stripped of international entanglements or obligations. He was scornful of the Commonwealth, loathed the “Special Relationship” with the United States and had little time for NATO.

My purpose here is not to argue that Powell was right or wrong, but to show the absolute, painful, scarifying nature of his intellectual approach to policy. This has been much on my mind—bear with me—as I have watched the race for the Republican nomination for president in this November’s election.

Former president Donald Trump declared he would seek another run at the White House on 15 November 2022 in an hour-long, rambling and falsehood-filled speech at Mar-a-Lago, his Florida resort and residence. He was almost the first candidate to declare—former Montana secretary of state Corey Stapleton had launched a doomed bid on 11 November—and it was not until 2 February 2023 that Steve Laffey, former mayor of Cranston, Rhode Island, a city of 83,000, joined the race.

14 February 2023 that Nikki Haley, former governor of South Caroline and US permanent representative to the United Nations, joined was the second major figure to declare her candidacy. Entrepreneur and wealth manager Vivek Ramaswamy was the fifth entrant, on 21 February, opening the floodgates: businessman Perry Johnson on 2 March, mergers and acquisitions guru and self-appointed pastor Ryan Binkley on 1 April, former Arkansas governor Asa Hutchinson on 2 April, radio host Larry Elder on 20 April, Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina on 19 May and, in a weird and accident-prone online announcement, Governor Ron DeSantis on 24 May.

More were to come. Also seeking the nomination were Governor Doug Burgum of North Dakota, Chris Christie, former governor of New Jersey, Trump’s estranged vice-president Mike Pence, mayor of Miami Francis Suarez, former Texas congressman and onetime CIA officer Will Hurd and soi-disant bishop E.W. Jackson. But an apparent free-for-all disguised the fact that the only slightly credible challengers to Trump were Haley, Ramaswamy, DeSantis and perhaps Christie. Writing today, as the first primary in New Hampshire is underway, the field has narrowed to two: Donald Trump and Nikki Haley.

Analysing the chances of these leading candidates, and of the sequences of events which might propel them to the nomination at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee in July has been a cottage industry for commentators. This isn’t meant as an attack on more distinguished colleagues in the commentariat, but we’ve read how Nikki Haley might pull it off, perhaps because she is “electable” on the national stage, earning endorsements from those who cannot countenance Trump; how Vivek Ramaswamy is a “breakout” candidate, with a number of routes to victory including being, in essence, a younger version of Trump; and how Ron DeSantis could confound expectation by winning, needs to embrace robust campaigning tactics and should not be counted out despite setbacks.

It has been tremendous fun, reading runes, searching precedents and hypothesising frantically. Different notions of “what might be” keeps writers, including me, in business. But all of this speculation has been carried out in the shadow of one enormous empirical fact. If you believe the opinion polls, Donald Trump has never seriously been challenged, let alone headed, and has always been the overwhelming favourite to take the GOP crown and face President Joe Biden in November’s poll.

Of course there are all kinds of variables. Opinion polls, as we all know, are not ironclad prognostications, those surveyed do not always tell the truth and we all readily think of the supposed surprises of the Brexit referendum of 2016 or Donald Trump’s first presidential victory the same year, the Conservative victory in 1992’s general election or Governor Tom Dewey’s failure to unseat President Harry Truman in 1948. It is also undoubtedly the case that Trump currently faces 91 felony counts in two state courts and two federal districts, and could perfectly well be given a custodial sentence between now and polling day on Tuesday 5 November.

That is all conjecture and hypothesis. The closest thing we have to empirical data are the opinion polls, and they indicate very strongly that Trump will cruise to victory in the nomination race. But there has seemingly been almost irresistible urge to explain why that will not happen. And it is obvious why.

Let me be unmistakeably clear. I do not support Donald Trump. I do not want him to be president of the United States again. I did not support him in 2016. I think he is an extremely bad man, possibly medically unstable, certainly indifferent to concepts of legality as well as constitutional and political propriety. He is certainly a crook, a liar and a bully, he has demonstrated an unwillingness to accept the results of the democratic process, and in his language and actions he is a clear threat to the political institutions of the United States. More alarmingly, and this is where the American electorate must own some of the fact of Trumpism, he has rarely tried to hide his nature, sometimes revelling in it.

I think he is worse and more dangerous now than he was in 2016. Eight years ago, though I didn’t in any way support or welcome his victory—though I think Hillary Clinton was a flawed candidate who fought a flawed campaign—I did push back against liberals who shrieked “Not my president!”, and I lost friendships over it, to my lasting and profound regret, because he was elected by the existing system, legitimately and properly.

My distaste, to put it mildly, for Trump 2.0 is widely shared. And the fact that many commentators don’t want to see a second Trump presidency has, I think, led many to look desperately for plausible ways in which he might be frustrated. We have played ourselves false, and we have ignored the preponderance of evidence as opposed to hypothesis because we have not wanted to believe that a shameless, narcissistic, crooked, mendacious braggart, found liable for sexual assault and defamation, could be elected to the most powerful office in the world. But this lacks honesty and rigour, and here is where I think the parallel with Enoch Powell’s views on India, the Empire and imperialism comes into play.

Fundamentally, political commentators, unless they are fully paid-up partisans, have value only insofar as they bring experience, learning, instinct and insight to explain what is going on and what is likely to happen. If that task is not carried out honestly and with regard to what we know to be true, it is useless. More than that, it can be misleading, and that can have real-world effects. If commentators mislead, then voters and politicians alike can make decisions based on false premises. To take a simple example, if one party is widely believed to be cruising to an easy victory in an election, it can lead its supporters not to turn out and vote, believing that the result is a foregone conclusion. If that belief is false, and based upon the misleading insights of commentators who are not being honest with themselves, the election can suddenly swing the other way on a narrow margin.

This goes wider, of course. Public policy cannot be sensibly made on false assumptions, something I have argued again and again that the Ministry of Defence is doing in terms of procurement and the capabilities of the armed forces (I will be writing about this in The Spectator very shortly, I hope). But it feels absurd that I should have to explain why an honest appraisal of facts and evidence is important in the sphere of political commentary.

However you are involved in public affairs, whether proposing policy, making decisions or analysing what has been, what is and what will be, there is one simple rule which is inviolable: don’t lie to yourself. Of course it can be more comfortable than facing reality. We don’t always get what we want and events can disappoint, frustrate and appal us. But internal, intellectual dishonesty serves no long-term purpose. All it will do is stave off the inevitable.

It really is that simple.

I wouldn’t go so far as to say “endorse”, and I don’t have a vote, but in a Biden/Trump contest, yes, of course, Biden is the less bad option. Still dreadfully inadequate but the lesser of two weevils, as Jack Aubrey would say.

The Trump affair is a weird one isn't it? All reporting, if honest, shows him to be a thoroughly hideous individual and yet millions will still vote for him knowing that. I'm a bit worried about Americans who do vote for him. The future is a worry.