Courtesy titles: an explainer

The eldest sons of senior peers can use a secondary title of their father's, but it is a loan, in a way; I will try to explain...

I will endeavour to make this brief and clear, but regular readers will know that while I can (I hope) achieve clarity, brevity is sometimes more elusive.

(I am reminded, as so often, of Stephen Fry’s The Liar. Adrian Healey, the eponymous fibber, tells his great love, Hugo Cartwright, with self-exasperation, “If I find a way of expressing adequately now what I am thinking and feeling you will take it to be a piece of verbal dexterity and the latest in a long line of verbal malversations. You see! I can’t even say ‘deceit’. I have to say ‘verbal malversations’.” While I am not habitually dishonest, the spirit of Healey resonates. And, indeed, off I go.)

This is based on a very small but niggling gripe, like a stone in my shoe, which is unimportant in the broad sweep but I think if one can get things right rather than wrong, one ought to do that. It’s a small matter of usage in peerage titles, and it is understandably easy to misunderstand, or just not to understand in the first place. I will try to make things clear and easy. I want to talk about courtesy titles.

The eldest sons of peers above the rank of viscount—that is, earls, marquesses and dukes—may use instead of their plain names their father’s second-most senior title, so long as it is not the same as his senior title. Let me take an easy example in the Duke of Marlborough. The holder of that title, like most senior peers, holds a number of subsidiary titles, so that he is also the Marquess of Blandford, the Earl of Sunderland, the Earl of Marlborough, Lord Spencer of Wormleighton and Lord Churchill of Sandridge. As a result, his eldest son may use the style “Marquess of Blandford” as a courtesy title.

One thing to note is that the duke remains, of course, the Marquess of Blandford, so his heir is “Marquess of Blandford” without the definite article. So the young man (actually he is 31) is George John Godolphin Spencer-Churchill, Marquess of Blandford. More commonly he is known as “George Blandford”; older readers will remember that the Duke of Marlborough, who had a rather wayward youth with drug addiction and prisons sentences featuring, was known in those days as Jamie Blandford.

There is an exception to this rule, which is if the peer’s second title has the same territorial designation as his senior one. Take the Duke of Westminster: his second title is also a marquessate, but it is the Marquess of Westminster. As it is the same territorial designation as the dukedom, it is not used as a courtesy title, but instead the heir goes to the third title held by the duke, that of the Earl Grosvenor. The title can be as low as a barony: the Duke of Somerset has only one subsidiary title, Lord Seymour, which is therefore taken by the eldest son.

This rule applies to marquesses and earls too. The Marquess of Bute is also the Earl of Dumfries (and the Earl of Bute and the Earl of Windsor) so his eldest son is known as Earl of Dumfries by courtesy. The 7th Marquess of Bute, who died in 2021, gained fame as a racing driver of considerable ability, winning the Le Mans 24 Hours in 1988 with Jaguar and was known during his professional life as “Johnny Dumfries”. (In 1986, he raced in Formula 1 alongside Ayrton Senna for Lotus; it was said, rather slightingly towards Dumfries, that Senna had vetoed Derek Warwick as a team-mate because he thought him too quick, but consented to be joined by Dumfries, who was coming from a disappointing season of Formula 3000.)

Courtesy titles can also extend to eldest grandsons, if there are enough to go around. If the eldest son of a duke, marquess or earl has a son, he may be known by the peer’s third title. In this way, the Duke of Marlborough’s eldest grandson, son of George, Marquess of Blandford, would be known by courtesy as Earl of Sunderland, except that Blandford has only a daughter, Lady Olympia Spencer-Churchill. But Lady Olympia is only three, so she may be joined by a brother in the future. The heir to the Duke of Buccleuch, Walter, Earl of Dalkeith, has a son, Willoughby, who carries the courtesy title Lord Eskdaill.

This all came into my mind because I was listening to an episode of the excellent podcast The Rest Is History on prime ministers and their departures, and the name of Lord North was mentioned. North is chiefly remembered as the prime minister “who lost America”, as he was head of the British government from 1770 to 1782, and ranks generally at the very bottom of lists of prime ministers, though some recent incumbents are now often in his company. It was said on the podcast that North was “actually” the Earl of Guildford, but this is not quite the whole truth: his father was created 1st Earl of Guildford, having been a Whig Member of Parliament, a gentleman of the bedchamber to Frederick, Prince of Wales, and briefly governor of Frederick’s son George, later George III. The father had previously succeeded a cousin as 7th Lord North, so once he became an earl in 1752 , his eldest son Frederick, then 20 years old, became Lord North by courtesy. It was under that title that he lived most of his adult life and served as prime minister, and MP for Banbury from 1754 t0 1790; his father died in August 1790 and he became 2nd Earl of Guildford, but died only two years later.

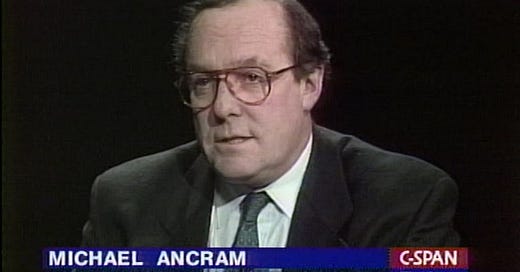

Most of you, I suspect, come here for politics. The heirs to peerages used to flit across the political landscape much more often than they do now, but most of you will remember the amiable Michael Ancram, whose career culminated in four years as deputy leader of the Conservative Party (2001-05). Ancram was notable for many reasons: he was a talented guitarist with a love of folk music and often entertained the Tory faithful at party conferences with renditions of Streets of London and Blowin’ in the Wind; he is also one of the few people to have represented three entirely distinct constituencies in the House of Commons, Berwick and East Lothian (February to October 1974), Edinburgh South (1979-87) and Devizes (1992-2010).

But Ancram is not, and was not, his name: he is Michael Andrew Foster Jude Kerr. His father, who died in 2004, was the 12th Marquess of Lothian, and Earl of Ancram is the courtesy title used by the eldest son. “Michael Ancram” is now therefore the 13th Marquess of Lothian, though, just to complicate matters, that hereditary peerage gives him no right to sit in the House of Lords: in 2010, he was awarded a life peerage, Baron Kerr of Monteviot, an accolade any long-serving shadow cabinet minister might expect. In the Lords, however, he is referred to by his senior title, the Marquess of Lothian, and is so recorded in Hansard. But for most of his professional life, he called himself “Mr Michael Ancram”, a weird melange of styles, supposedly because when he was in court as a young advocate he felt it would confuse juries if the judge addressed this young lawyer as “my Lord”.

(Some of his friends call Ancram/Lothian “Crumb”. Arriving at a party in the 1960s, he gave his name as “Lord Ancram”, and was then announced to the other guests as “Mr Norman Crumb”.)

Before the passage of the Peerage Act 1963, which allowed titles to be disclaimed, heirs to peerages served in the House of Commons under a kind of suspended sentence of electoral death, knowing that the demise of their father would see their career as an MP come to an end. Some did not like this stricture: Quintin Hailsham, whose father Douglas Hogg, one of the best lawyers of his generation, was created 1st Lord Hailsham on appointment as Lord Chancellor in 1928, had been ambivalent about his father’s promotion. Not only was Hogg Senior regarded as a very plausible contender for the premiership at some point, Quintin, then 20 years old, was an active student politician, at that time president of the Oxford University Conservative Association and soon to be president of the Oxford Union (Trinity term 1929). He was elected MP for Oxford at the famous by-election in 1938, and served in the House of Commons until his father’s death in August 1950, but he was always bothered by the fact that his ambition could not be for the highest political prizes.

I could write endlessly about Hailsham, for me one of the most interesting Conservative politicians of the 20th century, one of the most formidably intelligent and, bizarrely, for a while a correspondent of mine (or, I suppose, I was one of his). This is not the place. Note that he was “only” the son of a viscount and therefore as heir received only the prefix “the Honourable” which all children of barons and viscounts, and the younger sons of earls, receive. Heirs to baronies could not have courtesy titles, as a baron by definition has no subsidiary title; why the eldest sons of viscounts do not, I cannot say.

Courtesy titles seen in the Commons in relatively recent history were borne by Robert, Viscount Cranborne (MP for South Dorset 1979-87, now 7th Marquess of Salisbury); Maurice, Viscount Macmillan of Ovenden (MP for Halifax 1955-64, Farnham 1966-83, South West Surrey 1983-84, heir to the 1st Earl of Stockton but predeceased him); Johnny, Earl of Dalkeith (MP for Edinburgh North 1960-73, 9th Duke of Buccleuch); Oliver, Viscount Corvedale (MP for Dudley 1929-31, Paisley 1945-47, 2nd Earl Baldwin of Bewdley); Edward, Lord Stanley (MP for Liverpool Abercromby 1917-18, Fylde 1922-38, heir to the 17th Earl of Derby but predeceased him).

Winston Churchill was twice offered a dukedom. George VI offered to create him Duke of Dover in 1945, and Elizabeth II Duke of London in 1955, when he (finally) retired as prime minister. The great war leader declined on both occasions, at least partly so as not to endanger the Commons career of his son Randolph, which was a touching but ironically unnecessary consideration. Randolph had become MP for Preston unopposed at a wartime by-election in 1940 after three unsuccessful candidacies in the 1930s, but he lost his seat in the Labour landslide of 1945 and would never return to Parliament, though he stood against Michael Foot in Playmouth Devonport in 1950 and 1951. His brothers-in-law, Christopher Soames and Duncan Sandys, not only became MPs but cabinet ministers; his son Winston was MP for Stretford from 1970 to 1983 and Davyhulme from 1983 to 1997, and never achieved ministerial office, though he was an opposition spokesman on defence in the late 1970s.

Inevitably I have drifted somewhat from the original subject, courtesy titles. What I have said, I hope has been clear. Aristocrats sometimes hide in plain sight these days: from 2003 to 2014, the Metropolitan Police’s Royalty and Diplomatic Protection Department was headed by Commander Peter Loughborough, who was (indeed is) the 7th Earl of Rosslyn, “Lord Loughborough” having been his courtesy title before he inherited the title in 1977; racing driver Henry Arundel, who competed in British Formula 3 in 2008-09 and now works in insurance, is Henry Fitzalan-Howard, Earl of Arundel by courtesy and heir to Britain’s senior peer, the Duke of Norfolk; Henry Herbert, a film director who directed Malachi’s Cove and Emily in the 1970s as well as working on BBC classics Shoestring and Bergerac, was 17th Earl of Pembroke and 14th Earl of Montgomery but had risen to a modicum of professional eminence while styled Lord Herbert by courtesy.

I hope, therefore, that you are slightly better informed next time, should there be a next, or even first, time, you encounter someone who seems to be a peer yet might not be. I accept it’s all complicated; I have not even touched on the option of the heirs to Scottish peerages to use the style “Master of”, nor the various wrangles which Lord Lambton went through with the House of Commons authorities in the 1970s after he disclaimed the earldom of Durham but wanted to retain his courtesy title. Perhaps another time.

I cannot leave without an F.E. Smith anecdote, prompted by the opening of the previous paragraph. At one point during his legal career, a judge wearily said to him, “I have listened to you for an hour, and I am none the wiser.” Smith responded smoothly, “None the wiser, perhaps, my Lord, but certainly better informed.”