Counter-factual history: for good and bad

Imagining what might have been can be a useful part of the historian's discipline, provided one uses realistic parameters, and it reminds us that nothing is inevitable

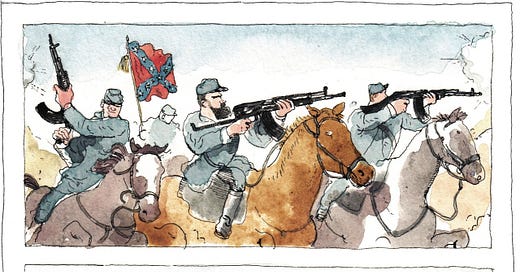

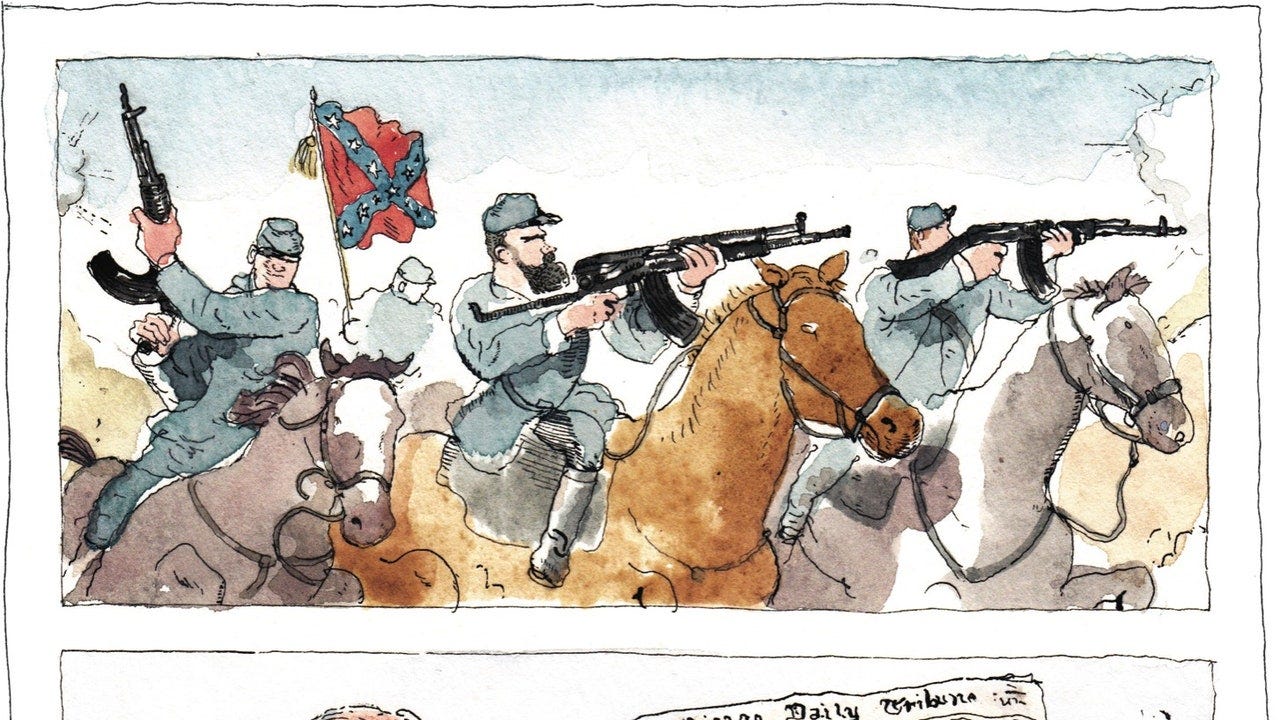

I have said before than I am a fan of counter-factual history, and have taken a lively interest in it ever since reading Niall Ferguson’s 1997 Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals. Partly it is an amusing parlour game, but I think it can hold useful lessons for historians because it reminds us that nothing is pre-ordained, and what can seem in historiographical terms inevitable was often anything but that to those living through it. Some regard it with scepticism, if not outright hostility, like Sir Richard Evans, former regius professor of history at the University of Cambridge, in his Altered Pasts: Counterfactuals in History (2014), and it is easy to mock bad or clumsy examples. It is striking, for example, how fond some parts of the far-right are of imagining military victory for the Confederacy, Nazi Germany or the Empire of Japan.

It is a genre, of course, and not all examples are the same. There is, for me, little scholarly worth in what-if scenarios which simply were never going to happen because circumstances made them near-impossible. That idea, for example, of the Confederacy winning the American Civil War is difficult to sustain when you consider that the South had a population of just over nine million, of whom 40 per cent were slaves, while the Union numbered more than 18 million and had almost all of America’s industry. Even if this or that battle had tipped in the other direction, a defeat for the Confederate States was always the most likely outcome so long as the Union held its nerve.

On the other hand, there are some historical events or moments of decision which really could have gone one of several ways and might have had a profound impact on the world. Here I set out three of them just to make readers think; I won’t dwell on them at great length, but may return to them in future weeks or months. You have been warned…

What if Katharine of Aragon had produced a male heir?

Almost every possible opinion on Henry VIII and his attitude to religion has been expressed and vehemently proposed. Was the Reformation a religious movement based on a rejection of the ideas of the Roman Catholic Church or a political stunt engineered to rid a horny, heirless king of his ageing wife? The truth, as so often in historiography, is a messy mélange of many elements: there was a long traditional of heterodox spirituality in England dating back at least to the Lollards of the mid-14th century; Henry VIII was perpetually aware of the insecurity of the Tudor dynasty and the overwhelming need for a male heir; the king had a notoriously wandering eye which met its match in Anne Boleyn, who refused simply to become another in a succession of royal mistresses.

So far as we know, Queen Katharine had six pregnancies during her marriage to Henry: in 1510, 1511, 1513, 1514, 1516 and 1518. Only one, the fifth, survived to adulthood, and the girl became Mary I. The first and sixth were also girls: one miscarried at six months in January 1510, and the other was stillborn in November 1518.

Between 1511 and 1514, then, Katharine gave birth to three sons. The first, born on 1 January 1511, was christened Henry and was Duke of Cornwall and heir apparent from the moment of his birth. However, on 22 February, aged 52 days, the infant died suddenly, and no cause of death is recorded. Another son was stillborn in September 1513, and a third met the same fate in November or December 1514. It was, however, a time of high infant and child mortality rates: the figures are hard to establish but something like a third of children may have died before they were nine years old. Two of the seven children of Francis I of France died in childhood, and four of Emperor Charles V’s children were stillborn or died in infancy.

Let us suppose, however, that Henry, Duke of Cornwall, born in 1511, had survived and flourished into manhood. By the time the King encountered Anne Boleyn, a lady-in-waiting to Katharine, the heir would have been 14 years old, on the cusp of adulthood: by that age, his uncle Arthur, Prince of Wales, was already lord warden of the Marches, with a household at Ludlow Castle and a Council of Wales and the Marches. If Henry had known he had a healthy male heir who would in time become king, would he have had the same impetus to put away the Queen and install Anne in her place?

While there were underlying factors which contributed to the success of the English Reformation, I think there are two considerations which suggest a male heir could have been transformational. The first was the extent to which the Reformation in England was a top-down, institutional, legislative process: the parliament which was summoned in August 1529 and sat until April 1536 stripped the clergy of legal privileges, restricted legal appeals to courts outside England, abolished papal jurisdiction and proclaimed Henry as supreme head of the church. It was the Ecclesiastical Appeals Act 1532 which contained the key phrase on which so much else was founded, the assertion “that this realm of England is an empire”. Without this direction from the centre, it is very doubtful that Protestantism would have made much headway.

The other issue, almost the reverse of the importance of state direction, was that, until reformist views became convenient, Henry’s government proved very willing to argue for and enforce Roman Catholic orthodoxy. The King, of course, wrote a polemic against Martin Luther entitled the Assertio Septem Sacramentorum (Defence of the Seven Sacraments), published in 1521 and restating unreformed Catholic doctrine. Moreover, the authorities remained strict in their prosecution of heretics. The first Protestant martyr, Thomas Hitton, was not executed until February 1530, having denied the authority of bishops, affirmed that Scripture was the only source of religious instruction and that the liturgy should be performed in English. All of these were heresies. At least eight other men lost their lives for heresy over the next three years. Meanwhile, St Thomas More, during his tenure as lord chancellor between 1529 and 1532, was active in rooting out heresy and using the judicial system to punish it.

On those grounds, there is certainly an argument that Henry VIII, without the abiding anxiety over the lack of a male heir, might well not have put his weight behind religious reform in the 1520s and 1530s, and perhaps would have been active in enforcing orthodoxy. Perhaps reformist spirituality would have come to England eventually, but it might have been much later, and in a very different, perhaps less dominant, form.

What if Queen Victoria had been a boy?

It is an odd fact of English and then British history that some of our longest-reigning monarchs have been women: Elizabeth I (1558-1603), Victoria (1837-1901) and Elizabeth II (1952-2022). Victoria’s reign saw fundamental change in the role of the monarch, from a still-active part of the constitutional arrangement to a more detached, advise-and-warn figure. For the first Elizabeth, female monarchy was a novelty in England, and only her predecessor and half-sister Mary I (1553-58) had tried it, if we discount Jane, the nine-day queen. Victoria’s legitimacy, however, was not challenged on the basis of her sex, and if she deferred to her husband Albert, the Prince Consort, it was as much by inclination as coercion. It was telling that, while Mary I’s husband Philip of Spain had been fully King of England alongside her, it was never seriously considered that Albert should be acknowledged or described as king after the prime minister, Viscount Melbourne, headed off an early suggestion from Victoria that he might be “king consort”.

Victoria’s sex, however, had one major effect. She succeeded her uncle, William IV, as sovereign of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, but he had also been King of Hanover, ruling a collection of territories in northern Germany which had its own legislature and was governed by a viceroy, latterly his brother, the Duke of Cambridge. The succession to the throne of Hanover, however, was regulated by a form of Salic law, the old Frankish custom which did not allow women to inherit or, in some cases, to transmit claims of inheritance. When William died in 1837, therefore, Victoria was ineligible to succeed him in Hanover, and the German realm passed to another of her uncles, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale. This ended the personal union between Britain and Hanover which had lasted since 1714.

Why is this important? Imagine Princess Alexandrina Victoria had been born Prince Alexander Victor: “he” would have succeeded William IV as King of the United Kingdom on 1837 just the same, but “he” would also have been King of Hanover, maintaining the personal union. If “he” had lived until 1901, could there have been any unification of Germany in 1871? After all, a portion of the North German Plain would have been under the control of perhaps the world’s greatest imperial power, and the UK would hardly have allowed Prussia effectively to annex part of its territory. If there had been any move towards the unification of Germany, it might have been some smaller version of the North German Confederation, or could have looked south to the German-speaking lands of Austria. How does history up to 1914 play out if there is no Germany as we know it?

What if the July plotters had killed Hitler?

The assassination attempt against Adolf Hitler on 20 July 1944 was implausible in a lot of ways. It was the latest in a long line of slightly chaotic and unsuccessful plans to kill the Führer, and it was a triumph of spirit over practicality that the task was entrusted to a badly wounded staff officer who was missing his left eye, his right hand and two fingers on his left hand. Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg spent three months in hospital in Munich after his column was strafed by an Allied fighter-bomber in Tunisia in April 1943, and he joked that he had never really known what to do with so many fingers when he still had a full compliment.

The details of the unsuccessful assassination are well known. With only three fingers, Stauffenberg was only able to arm one of the bombs which he had brought to Hitler’s East Prussian headquarters, the Wolfsschanze (“Wolf’s Lair”); he placed his briefcase containing the bomb as close to Hitler as he could then excused himself from the briefing room; another officer, Colonel Heinz Brandt, moved the briefcase innocently, putting it on the other side of a heavy wooden table support from Hitler; when the bomb went off, although Stauffenberg thought no-one in the conference room could have survived, only one person, a stenographer, was killed straight away, three more died later and the other 20 were injured to varying degrees. The Führer himself, shielded by the table support, suffered a perforated eardrum and conjunctivitis in his right eye but was not seriously wounded.

From that moment, the survival of Hitler, the coup was doomed. It unfolded swiftly and brutally, with the leaders being seized in Berlin and executed after a summary court martial in the early hours of the following day, 21 July, and over the following weeks the Gestapo swept up anyone even remotely connected with the conspirators. More than 7,000 people were arrested and 4,980 were executed, some with no involvement at all as the Gestapo took the opportunity to settle old scores. Could it ever have worked, and what would have happened?

One important consideration is that the plotters were by no means peace-loving democrats. Stauffenberg, while sceptical of Nazism, was also dubious about parliamentary democracy. Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, a Prussian civil servant slated to be chancellor in the post-coup government, had at first considered Hitler an “enlightened dictator” who would be a force for good if properly controlled, and for a while sought the restoration of the Hohenzollern monarchy. Colonel General Ludwig Beck, intended as president in the new régime, never joined the Nazi Party but had supported Hitler’s militarism including his renunciation of the Treaty of Versailles.

The aim of the plotters was to remove Hitler and install a government which could reach a negotiated peace with the Western Allies before Soviet forces invaded German territory. But they generally regarded the continuation of the war with the Soviet Union as essential and existential, being almost universally firmly anti-communist. It is possible that, if Hitler had been killed, the conspirators might have been generated sufficient momentum to rally to their cause both those who disliked Hitler and the Nazis, and those who were well enough attuned to self-preservation to fall in behind a successful coup. Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, after all, ended up trying to treat with the Allies in April 1945 without Hitler’s approval, so was clearly flexible in his loyalties when the chips were down. Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, albeit addled by morphine addiction, also freelanced in the last days of the war, though he perhaps genuinely believed he was acting in the Führer’s best interests.

The principal difficulty would have the Allies themselves. By July 1944, US and British forces had broken out of the toeholds in Normandy seized on D-Day and were at the outskirts of Caen. Although the Wehrmacht was putting up fierce resistance, the Allies had almost complete air superiority, making their victory, at least in France, only a matter of time. In any event, however, President Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill had met at Casablanca in January 1943 and agreed a declaration which stated that the Allies would accept nothing less than “unconditional surrender” by Germany.

It is true that the Casablanca conference did not leave the matter closed. Churchill regarded Hitler as the principal enemy and obstacle to peace, but also distrusted Stalin and the Soviet Union’s intentions towards eastern Europe; Allen Dulles, head of the Office of Strategic Services in Switzerland (and later director of the CIA 1953-61), thought the declaration was “merely a piece of paper to be scrapped without further ado if Germany would sue for peace. Hitler had to go.” Some members of the anti-Hitler resistance seem to have been in contact with the UK’s Secret Intelligence Service to explore co-operation or support.

Would the Allies have listened by July 1944? It seems at least doubtful. Even if a new German government had taken power and abjured Nazism and the worst atrocities of the Nazi régime, it is hard—though not impossible—to imagine the Western Allies reconfiguring their diplomatic and military efforts to repudiate their alliance with the Soviet Union and accept Germany as a partner. Moreover the prospect of a renewed, almost reset, conflict after five years of war, in the UK’s case, would have seemed exhausting. For all that, one has to suppose that a German government led by anyone other than Hitler might not have dragged the Second World War out to its brutal and shattering Götterdämmerung in Berlin in April/May 1945. It is worth remembering that German military losses in 1945 alone are estimated at 1.5 million dead.

Conclusion

My point is that the changes at the heart of these scenarios are small and perfectly possible. They don’t require a lesser global power somehow to defeat a much greater one, or some far-fetched set of circumstances to come together. But the effects could have been huge, resonant, cascading down centuries. And they were not pre-ordained: the Tudor court in the 1510s had no reason to think that the King and Queen would fail to have a male heir, and the July 1944 conspirators got surprisingly close to killing Hitler and had made plans for the eventuality of success. Too often we see history as a path of events leading a fixed outcome, but it never looked that way to those living through the events in question.

I will leave you with a remark reported by John Foxe, the Protestant propagandist, in his Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church (better known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs). He tells the story of a justice of the peace in Lancashire, a man named Thomas Lelond, who was engaged in finding and prosecuting heretics in the last months of Mary I’s reign in 1558. Lelond was reminded that the childless queen’s heir, her half-sister Elizabeth, was a Protestant, and that Protestantism might soon be back in the ascendancy. He was resigned, but not fatalistic.

“Thou old fool, I know myself that this new learning shall come again; but for how long?—even for three months or four months, and no longer.”

It was not an outrageous suggestion, though it proved very, very inaccurate. And we still have an established Protestant church now, 450 years later.

I've a huge fondness for counterfactual history, the only field in which I have been published. But I take the point that it's the soft porn of history. It's historical masturbation, fun but essentially unproductive.