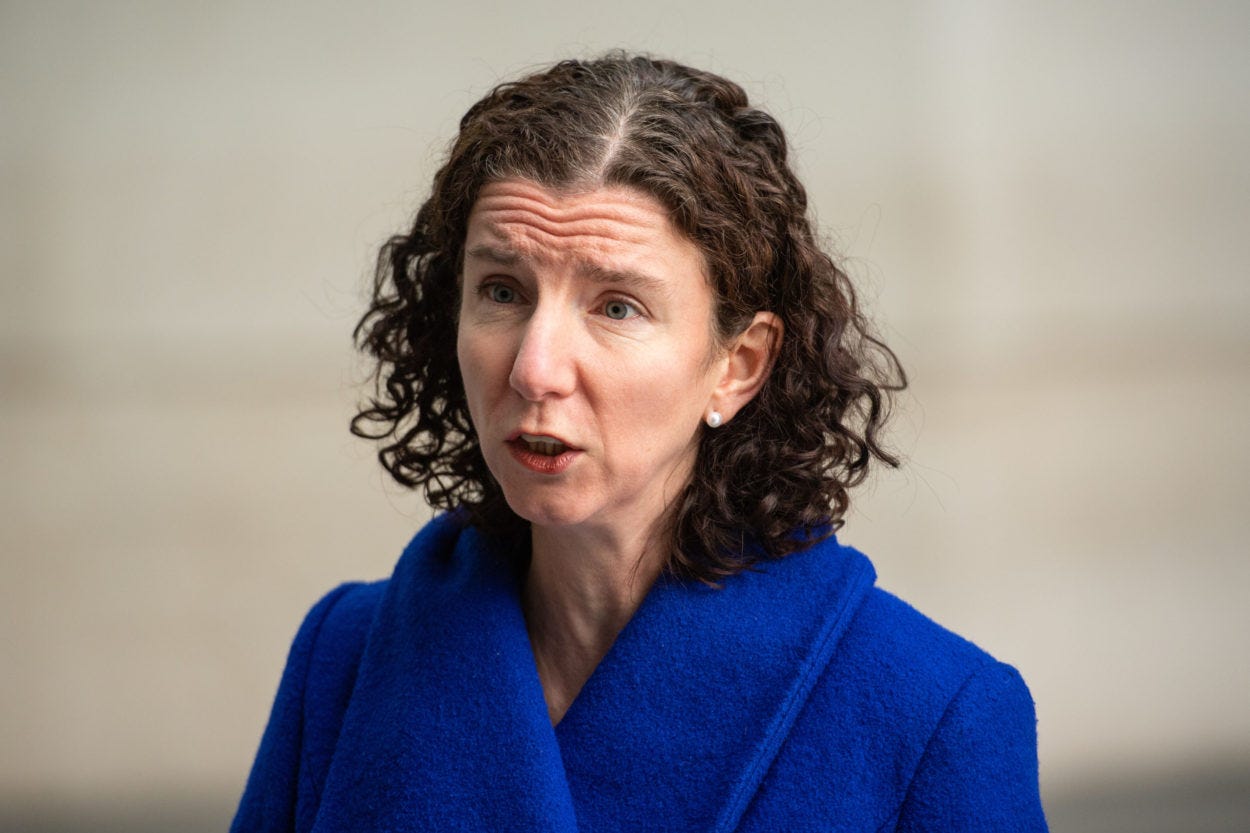

Anneliese Dodds, international aid and the defence of the realm

After the announcement that increased defence spending would be funded by a cut in the overseas aid budget, the minister in charge has resigned

Without wishing to be unkind, “Anneliese Dodds resigns” is not a headline to keep a prime minister awake with anxiety in the long watches of the night. The Oxford East MP has quit her post as Minister of State (Minister for Development) at the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office in protest at Sir Keir Starmer’s decision to pay for an increase in defence spending from 2.3 per cent of gross domestic product to 2.5 per cent by reducing what is officially termed Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) from 0.5 per cent of government expenditure to 0.3 per cent.

In her resignation letter to the Prime Minister, Dodds argued that it was the manner and extent of the decision more than the principle behind it which had made her conclude her position was untenable. She agreed that it was necessary to increase expenditure on defence and accepted that, in terms of savings elsewhere across government, “some might well have had to come from ODA”. But she was disappointed that there had been no discussion of the policy—Starmer is said to have informed the Cabinet at its meeting on Tuesday morning shortly before announcing it in the House of Commons rather than allowing a debate and collective decision-making—and she felt that the decision to fund the additional spending wholly from the aid budget had been taken for tactical reasons rather than as part of a coherent strategic vision. She was particularly concerned that “this decision is already being portrayed as following in President Trump’s slipstream of cuts to USAID”.

Dodds set out a predictably heart-breaking list of programmes which would lose funding and vulnerable groups which would be affected by a reduction in aid. She also claimed it would lead to the United Kingdom being “shut out of numerous multilateral bodies” and seeing its influence lessen in the G7, G8 and climate change negotiations. Essentially, spending less money on international development will, in her view, lead to reputational damage for the UK.

The fall-out from Dodds’s resignation

It is worth saying straight away that Dodds’s decision is honourable and intelligible, a straightforward issue of principle on which she cannot support the government of which she had until today been a member but not an indication of her wholehearted opposition to Starmer’s leadership or the policy direction of the Labour Party. She deserves at least recognition if not actual credit for that stance, as she could perfectly easily otherwise have eked out a mid-level ministerial existence for the rest of this parliament if she had looked the other way. That is not a small thing: however much politicians who have served in the middle ranks of government complain at their relative impotence and the scale of the challenge of getting anything done in Whitehall, ambitious MPs who turn down even the most unglamorous and superficially dreary ministerial positions are rare indeed.

That must be balanced by an acceptance that Dodds’s departure will make absolutely no difference to the direction of government policy nor, I suspect, to the security of Sir Keir Starmer’s position. Andrew Marr has written a cautionary article in The New Statesman which talks about the Prime Minister’s need to placate the Labour Party’s “soft left”, of which he holds up Dodds as a leading figure. For all that Starmer is struggling much more than anyone could have predicted before the general election, I think Marr overestimates the challenge he faces from that direction, given a relatively unified cabinet, a working majority in the House of Commons of 167 and an Official Opposition still firmly in recovery mode. There is also no evidence that cutting international aid is unpopular with the majority of voters.

Who is Anneliese Dodds?

In any event, Dodds herself is not a transformational figure. It is easy to forget but she was Starmer’s first choice as Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer when he became Leader of the Labour Party in April 2020, despite some of his advisers pressing the case of Rachel Reeves, then Chair of the House of Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee. Dodds, a philosophy, politics and economics graduate of St Hilda’s College, Oxford, had earned a master’s degree in social policy at the University of Edinburgh then been awarded a doctorate for a thesis entitled “Liberalisation and the public sector: The case of international students’ policy in Britain and France” at the London School of Economics.

(Rachel Reeves was a contemporary and fellow PPE student at Oxford, though at New College, and also overlapped with Dodds at the LSE; Nick Thomas-Symonds, Paymaster General and Minister for the Cabinet Office, was reading PPE at St Edmund Hall; Miatta Fahnbulleh, Minister for Energy Consumers, was undertaking the course at Lincoln College; Stephen Doughty, Dodds’s fellow Minister of State at the FCDO, was a PPE undergraduate at Corpus Christi; Emma Reynolds, Economic Secretary to the Treasury, was reading PPE at Wadham College.)

Dr Dodds then joined academia as an expert in regulation and risk in the public sector. She lectured at King’s College London from 2007 to 2010 then Aston University from 2010 to 2014, was published in learned journals and wrote a textbook entitled Comparative Public Policy. Despite her worthy but dry academic specialism, she was also an active political campaigner: she had been President of Oxford University Student Union as an undergraduate, and a vocal critic of tuition fees, and was a Labour candidate at the general elections of 2005 (in Billericay) and 2010 (in Reading East). In May 2014, she was elected as a Member of the European Parliament for South East England, but stood for Westminster in the snap general election of 2017 and was elected MP for Oxford East, by then a reliably Labour seat, when former cabinet minister Andrew Smith retired.

Although assessed by most as on the “soft left” of the Labour Party and described as a “unity” candidate, Dodds was comfortable with Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership (although she had supported Yvette Cooper in the 2015 contest to replace Ed Miliband). Shortly after the election, she was appointed Shadow Financial Secretary to the Treasury, promoting “smarter” regulation of the financial system and increased support for those who were long-term unemployed or in need of retraining. She was in favour of raising corporation tax so that “those with the broadest shoulders” contributed more to the public finances.

A “soft left” public policy academic specialising in public sector regulation who had previously been an MEP and served on the European Parliament’s Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs: Dodds was exactly as dynamic and exciting a politician as you would expect. Undoubtedly clever and intellectually able, and possessing genuine policy expertise, she had nonetheless done nothing in her three years in Parliament by the time Sir Keir Starmer became Leader of the Labour Party to suggest she would be prominent in its higher echelons. However, as Patrick Maguire related in The Times on Friday morning, she had struck up a rapport with the leader during the course of a long car journey to a trades union hustings.

Starmer wanted “a shadow chancellor who best expressed his conciliatory, pluralistic, fudgy brand of Labourism”, and that was certainly a description which could be applied to Dodds. She had supported his leadership bid, was popular with fellow MPs and came with the good offices of Corbyn’s Shadow Chancellor, John McDonnell, who thought her “really talented, works incredibly hard and is conscientious in all she does”. That she was regarded as a good media performer was a more eloquent commentary on Corbyn’s front bench than on Dodds herself: he was at the head of a team which included low-wattage or outright catastrophic mouthpieces like Rebecca Long-Bailey, Richard Burgon, Dawn Butler and Jon Trickett. One quality which is said to have struck a chord with Starmer was her background as an academic and the calm, level-headed, evidence-driven approach to policy it had inculcated in her.

It was never going to work. When Starmer became Leader of the Labour Party, just before the Covid-19 pandemic fully broke, Boris Johnson was a dominant prime minister who had just won an impressive majority at the 2019 general election and seen Labour record its worst performance since 1935. The amount of public attention, never mind sympathy, available for a defeated opposition party about to mark a decade since leaving office was tiny, and it would be a formidable challenge for two or three leading Labour figures other than Starmer himself to make any impression. Despite holding the key role of Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, this was a challenge to which Dodds was simply not equal. She could make virtually no headway against the new Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, whose principal role during the pandemic was to open the taps of public expenditure and disburse money to keep the economy afloat. In addition, in those early days, Sunak, only 39 years old when appointed and with the sheen of high finance and a California hedge fund background, had a sharp media team around him, most notably Nerissa Chesterfield, and was developing a strong personal brand.

(He was another Oxford PPE graduate, having studied at Lincoln College while Dodds was at St Hilda’s.)

After disappointing results in the local elections in May 2021, and under pressure over his leadership generally, Sir Keir Starmer conducted a broad reshuffle of his shadow cabinet to try to give the Labour Party a sharper, fresher edge and promote more convincing spokesmen and women. While only two people left the shadow cabinet altogether—veteran Chief Whip Nick Brown and Valerie Vaz, Shadow Leader of the House of Commons—Dodds was moved from the Treasury brief and instead appointed Chair of the Labour Party. It was a largely administrative role, barely even full-time and only created in 2001, and the most favourable interpretation could not disguise the fact she had been demoted, though the blow was softened by giving her responsibility for the party’s policy review.

In September 2021 Dodds was given the additional role of Shadow Secretary of State for Women and Equalities, shadowing a non-existent role but putting her in charge of a policy area in which she has subsequently struggled as it has become more controversial and divisive, especially on issues of gender identity and rights. She retained a seat in the shadow cabinet until the general election but had clearly become a marginal figure.

When Labour took office in July 2024, Starmer used the opportunity of Thangam Debbonaire’s defeat in Bristol West and the subsequent appointment of Shadow International Development Minister Lisa Nandy as Culture, Media and Sport Secretary to place Dodds as a minister of state at the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, in charge of international aid. (It had previously been Labour policy to restore the Department for International Development, established by Tony Blair in 1997 but merged into the Foreign Office in September 2020, but this was gradually downplayed and then abandoned.) She was also made Minister of State for Women and Equalities as second-in-command to Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson in the Women and Equalities Unit.

The immediate consequences of Dodds’s departure

I rehearse this at some length because Dodds’s standing in the Labour Party is important in terms of the likely impact of her resignation. There is no doubt that the Prime Minister’s decision to use only the aid budget to fund the increase in defence spending has caused dismay, disappointment and anger among many of the party’s supporters and activists, as well as the development and NGO establishment with which Labour has traditionally enjoyed cordial relations. As I mentioned earlier, this anger is not, it would seem, matched in extent or vehemence in the wider electorate; that aside, a more disruptive and weighty figure, carrying the moral authority of a resignation from ministerial office purely on a matter of principle, could cause real trouble for Starmer within Labour.

Anneliese Dodds is not that person. That is in many ways to her credit: her resignation letter, while it hinted at genuine anger that there had been so little consultation on the decision, was courteous and regretful. She made clear that she was still broadly supportive of the government, and it is significant that she chose not to announce her resignation until Starmer had returned from his encounter with President Donald Trump in Washington; no-one supposes that the departure of a middle-ranking minister would have overshadowed the meeting, but it would have been a potential distraction which Dodds, thoughtfully and responsibly, chose not to cause.

It is possible that Dodds will choose to make a personal statement on her resignation in the House of Commons in the near future; it is an option open to her but not a requirement. If she does, it is extremely unlikely to be an attempted philippic like those of Sajid Javid in 2022 or Boris Johnson in 2018, let alone Sir Geoffrey Howe’s 1990 archetype of the genre. She is not a plausible ringleader of backbench dissent, but that would anyway be a difficult task in the current circumstances: of the 411 MPs who were elected under the Labour Party banner last July, 231 of them are new. Having been in Parliament for only eight months (of which two were taken up by the adjournments for summer and the party conferences), they have not formed entrenched cliques or conspiracies and do not have long experience of the atmosphere of Westminster and the rhythm of discontent. Starmer also holds the power of patronage, of ministerial promotion, and, with the first planned reshuffle of his administration rumoured to be scheduled in late spring or early summer, ambitious Labour MPs will have reason to stay in line for the time being.

Guns v. butter: has Starmer got it right?

I have argued again and again that the United Kingdom needs to spend more money on defence, and that increasing the military budget to 2.5 per cent of GDP, as Starmer is now promising to do, is necessary but not sufficient. I wrote in The Spectator this week that the additional resources should more or less be enough to allow the armed forces to fill their current and significant capability gaps and enable them to carry out the commitments we have already made.

The example I often rely on is this: NATO planning assumptions include the UK contributing the British Army’s major war-fighting formation, 3rd (UK) Division, as a key component of the Allied Rapid Reaction Corps (ARRC). The ARRC is commanded by a British three-star general (currently Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Wooddisse) with its headquarters at Innsworth near Gloucester, and is designed to deploy substantial ground forces at short notice to meet any threats to the alliance. 3rd (UK) Division, around 15,000 soldiers, would be one of probably five divisions comprising the ARRC at full strength, but its current strength and lack of equipment mean that it could probably only generate a single combat brigade of 4,000-5,000: Dr Jack Watling of RUSI explained why recently in The Daily Telegraph. His colleague Matthew Savill has described the idea of the UK deploying a full division as “fanciful”. Yet on paper that is part of NATO’s establishment.

It was inevitable that an increase in the defence budget, given the sluggish condition of the economy and the absence of any meaningful growth, would entail cuts in expenditure elsewhere in Whitehall. Even Anneliese Dodds acknowledged as much in her resignation letter. However, it is slightly surprising that the Prime Minister has chosen to take all of the money required from one other source in a self-sealing move, rather than as an integrated part of a wider settlement. The Chancellor and her deputy, Chief Secretary to the Treasury Darren Jones, are currently undertaking a spending review which will allocate resources across government; the results of the review are due to be announced in “late spring of 2025” (which, based on experience, could mean anything from April through to June, given the flexibility civil servants apply to seasonal terminology).

It is worth noting at this point that taking the money from the aid budget in particular is problematic, as it is the only part of government expenditure which is prescribed by law. The International Development (Official Development Assistance Target) Act 2015 stipulates that spending on official development assistance (ODA) must amount to at least 0.7 per cent of gross national income, and, if it does not, the minister (at that point the International Development Secretary, now the Foreign Secretary) must lay a statement before Parliament explaining why the target has not been met, and what steps will be taken to restore it to the 0.7 per cent minimum.

In November 2020, the Foreign Secretary, Dominic Raab, announced that ODA would be reduced to 0.5 per cent of GNI as a “temporary measure” due to the Covid-19 pandemic; it was 0.5 per cent in 2021, 0.51 per cent in 2022, 0.58 per cent in 2023 and is expected to 0.5 per cent for 2024. In the Budget Report published in October 2024, HM Treasury said that “the government remains committed to restoring ODA spending to 0.7% of GNI as soon as the fiscal circumstances allow”, but warned that, according to the forecast of the Office for Budget Responsibility, the fiscal tests applied to restoring ODA to 0.7 per cent were unlikely to be met during the current parliament, that is, before 2029. This week’s announcement stated that it will now be reduced to 0.3 per cent.

There is an interesting legal argument to be had around the precise requirements of the 2015 Act can and must be met, and how much leeway they allow. In 2021, Lord Garnier, former Solicitor General, argued that it was unlawful for the Foreign Secretary deliberately and knowingly to fail to achieve the 0.7 per cent target, an opinion supported by former Director of Public Prosecutions Lord Macdonald of River Glaven. However, speaking for the government, Lord Agnew of Oulton, Minister of State at the Cabinet Office and HM Treasury, told the House of Lords that the spending decisions taken were “in line with the spirit and framework of the Act” and that no further legislation was required. Given that the Prime Minister has announced a reduction to 0.3 per cent of GNI as a matter of policy, I assume that the government can no longer be considered to be conforming to “the spirit and framework” of the 2015 Act and that it will be amended or repealed. That will be an uncomfortable legislative process for ministers.

I will note here that I think the repeal of the act is a good thing, not because of the specific value or otherwise of ODA but because I don’t think circumscribing spending decisions through statute is appropriate or effective. Governments should be free to allocate their resources how they wish, for which they are accountable to Parliament and, eventually, to the electorate, and one parliament should not seek to circumscribe a government drawn from a future one. In any event, as the 2015 Act has proven, it simply does not work: it applied for only five years, 2016 to 2020, and since then has been ignored with impunity as a “temporary measure”. It therefore exists as a declaratory law, an indication of good will and intent with no practical effect, and, as I have written before, that is now what Parliament or legislation are for.

Starmer has made his decision, in any event, and the increase in defence spending will, he claims, be met solely from money taken from the ODA budget. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has argued that any expenditure on the armed forces beyond 2.5 per cent of GDP, as the Prime Minister promised some time in the next parliament if circumstances allow, will require additional taxation or spending cuts elsewhere; it also pointed out that the additional £13 billion a year which the government was suggesting the Ministry of Defence would receive was a misleading calculation, justified only on the assumption that spending would otherwise have been frozen in cash terms. In fact the increase is likely to be around £6 billion.

Weighing the arguments

There has been vehement opposition to the reduction of the ODA budget from some Labour MPs and, naturally enough, organisations involved in spending and distributing the aid. It has been pointed out, quite accurately, that this is the largest single cut in UK overseas aid since records began, and there is, quite rightly, widespread dismay that, even before the cuts were announced, 28 per cent of the government’s aid budget was being spent by the Home Office to house asylum seekers in the UK awaiting decisions on their status. That is, in my view, an unacceptably high sum of money, nearly £4.3 billion, and it should not be included in the aid budget, but those are separate and different arguments.

On Tuesday, I spoke to Kait Borsay on Times Radio’s The Evening Edition (here, starts 1.37.47) alongside Dan Paskins, Interim Executive Director of Save the Children, and we covered many of the arguments briefly. If I can summarise crudely, however, the two principal criticisms levelled at the government are that cutting the aid budget will, obviously enough, directly and adversely affect vulnerable groups, in some cases among the most vulnerable in the world; and that moving money from aid to defence is, as many have described it, a “false economy” because assistance to poorer countries helps prevent conflict, encourage economic growth, mitigate climate change and—an appeal to self-interest here—ultimately will drive down international migration by making it easier and more attractive for those in low-income regions to remain where they are but still improve their living conditions and prosperity.

On the first point, of affecting vulnerable groups, I freely concede that almost inevitably that will be the case. If the United Kingdom, which is the third largest national source of development aid after the United States and Germany, reduces its expenditure by nearly half, that is bound to have consequences, and it is in the nature of overseas aid that its recipients are poor and vulnerable. I would counter by saying that if we need to spend more money on defence, of which I am quite certain and is now very widely accepted, given the current global security situation and the condition of our armed forces, then that money must come from somewhere. If it is not to come from ODA, it is incumbent on those who oppose that choice at least to suggest an alternative source.

It is politically all but impossible for the government to reduce expenditure on healthcare provision or education, and reforms to welfare spending have already proved extremely controversial in the case of restricting the Winter Fuel Payment to those on means-tested benefits. The government has also committed to investing in and improving the country’s infrastructure and increasing the availability of housing, which reduces any scope for money to be taken from the Department for Transport or the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. From where else, then, can the resources be reallocated? I would not argue that the aid budget is the only possible source or that it is wise to seek only one source for the money, but I do accept that the government’s room for manoeuvre is, for political reasons, very limited. As I said on Times Radio on Tuesday, it has to come from somewhere.

The other argument, that reducing overseas assistance is short-sighted because it that assistance is a powerful driver of stability and makes conflict less likely, is a challenging one. Intellectually, it is a coherent series of propositions. The Foreign Secretary, David Lammy, commissioned a review last September by Baroness Shafik, former Permanent Secretary to the Department for International Development, to examine “how to maximise the UK’s combined diplomatic and development expertise in its international development work” and ways to “modernise the UK’s development offer in a rapidly changing global context”; as of 20 January this year, he was “considering the recommendations” of Shafik’s review, but these had not been made public. We can at least hope that they were acknowledged in any discussions about reducing ODA, though I am not confident that will have been the case.

On a superficial level, however intellectually coherent, the evidence seems slight. If we consider the years form 2016 to 2020 as the peak of UK aid spending, it cannot be described as a golden age on the international stage. We can set aside as sui generis aid given to Ukraine, as that was a combination of military, financial and development aid to help defend the country against aggression, and Ukraine does not fit the ‘typical’ profile of a major recipient of UK aid. The top five destinations of bilateral aid from the United Kingdom in 2023/24 were Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Ukraine, Nigeria and Yemen; it is easy to spot the odd one out.

It is, of course, difficult to quantify conflict prevention and any resulting lack of adverse consequences. ODA enthusiasts do have a tendency to talk in generalised, high-level terms about the benefits of aid in this regard, but, just to look again at those five nations who benefit most from bilateral aid from Britain, Afghanistan has been wracked by violence for decades and fell once more under the control of the Taliban when Western forces withdrew in 2021; Ethiopia has been enduring a (second) civil war since 2018, accompanied by a rise in ethnic violence and the internal displacement of hundreds of thousands of people, perhaps as many as 400,000 by 2017; and there has been a civil war in Yemen since 2014, in which Saudi Arabia intervened with military force at the cost of tens of thousands of lives and accusations of war crimes, while Houthi militants in Yemen have launched armed attacks against maritime commerce in the Red Sea since the end of 2023.

Elsewhere in countries which receive UK aid, the civil war in South Sudan has led to a major refugee crisis, with 2.1 million people having left the country by 2017 and 2.4 million by 2022, in addition to two million internally displaced people. Syria is only just beginning to stabilise after the fall of President Bashar al-Assad in December last year. Meanwhile Somalia, another major recipient of aid, was declared a failed state in 2011 and, although there is some progress in building institutions and encouraging economic growth, the country remains extremely poor, authoritarian and corrupt, a safe space for Islamist terrorist groups and likely to remain dependent on aid for many years to come.

As for the issue of migration, the evidence is far from conclusive. A recent study in World Development suggested that, under some circumstances, economic growth in poorer countries actually led to more, not less, emigration; and it is self-evidently the case that countries like the UK, France and Germany will remain relatively speaking more prosperous and therefore offering more opportunities than developing economies, no matter how much growth they experience.

On the whole, then, I think the evidential basis for some claims about the benefits of ODA to the donor countries is weak. Some have argued that development aid is an ineffective method for achieving its stated aims under any circumstances; for example, see this paper by Ian Vásquez for the Cato Institute in Washington DC. I would not seek to argue that we should scrap foreign aid altogether, but the claims made for it, when set against the pressing urgency of properly funding the armed forces, are simply not sufficiently compelling.

One critcism of the Prime Minister which fails to hold water, I think, is that semi-articulated by Dodds in her resignation letter that Starmer is “following in President Trump’s slipstream of cuts to USAID”. She distanced herself with the weasel-word formula that the decision was “being portrayed” that way rather than saying it was something she believed, but as a theory it fails to pass the sniff test. Would the Prime Minister really more-or-less halve the UK’s aid budget and endure the criticism and dissent he has already experienced, or contemplate the sheer gravity of the move in psychological terms, for the sole purpose of being able to point to some weak emulation of the campaign against USAID by Elon Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE)? It seems glaringly disproportionate and implausible. The meat of what Starmer was taking to Washington was his commitment to increasing defence spending, an area which the President and the Secretary of Defense had specifically cited, while the source of those additional resources seems very peripheral.

There is one final factor which I will sketch out briefly but which deserves much fuller explanation and analysis at a future date. All public policy areas have vested interests and individuals and organisations identifiable as “the usual suspects”; in defence terms, you would look at think tanks like RUSI, the Centre for Defence Studies at King’s College London and the International Institute for Strategic Studies; the defence industry; and former service personnel, especially retired senior officers, among others. That is no less true in the field of international development, where there is a strong “establishment” of charities, NGOs, international organisations, academics and analysts and elements of the private sector and entrepreneurs.

The development establishment, in my anecdotal experience, is distinguished from “stakeholders” (a loathsome word) in many other policy areas by a strong sense of moral purpose which can easily become self-righteousness. After all, its raison d’être is the alleviation of poverty, disease and suffering of all kinds. Some of the reaction to Starmer’s decision to reduce the ODA budget has shown the way this can ossify into certainty from which there is no persuasion: some critics seemed to suggest, even of only implicitly, that any reduction in overseas aid was an assault on the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people, and therefore immoral and an affront to decency. Clare Short, who was International Development Secretary from 1997 to 2003, was particularly dismissive and high-minded in her criticisms of the government when she spoke to LabourList a few days ago.

It doesn’t understand that good development work is crucial to a sustainable future. It splashes money on defence spending and Ukraine and is not focused on bringing peace to Ukraine—and disgracefully, it has still not abolished the two-child benefit cap. I am afraid that, in many respects, this is simply not a Labour government… the morally concerned middle class, internationalists and supporters of the United Nations and international law, will splinter and the traditional Labour Party will be destroyed.

Now, it is only fair to observe that Short has been out of office for more than 20 years and left Parliament 15 years ago. She is also pulling a number of other issues into the debate about overseas. She is, bluntly, of limited relevance to contemporary politics as an individual, but the argument she articulated is not unique.

At the risk of creating a caricature, there is a sense that those involved in development are assured of the rightness of their mission and feel they should be left alone to pursue it, while the messy and painful compromises of balancing the government’s budget should be someone else’s responsibility. That argument cannot be countenanced. There cannot be areas of public expenditure which are, so to speak, morally ring-fenced, their practitioners insulated from financial reality. In any case, while it is broadly true that the motivation behind international development is noble and generous, but it is by no means immune from inefficiency, corruption and egregiously poor decision-making, while the revelations of unacceptable or outright criminal conduct at charities like Oxfam and Save the Children proved that their are malign forces in every area of life and no-one should take moral high ground for granted.

“When I ask ‘what’s next’, it means I’m ready to move on to other things, so: what’s next?”

The reduction in the overseas aid budget is a choice which Sir Keir Starmer will not have taken lightly. Even if you are unwilling to ascribe any moral hesitation to him, he will have known that moving money from development to the armed forces will be deeply unpopular with some of the Labour Party’s natural supporters and with many people with whom he is in ideological sympathy. The Prime Minister’s global outlook is very much a liberal and progressive one which believes in international law, supranational justice and an obligation on richer countries to help those which are less prosperous. I welcome the fact that he has finally set out a timetable for the increase in defence spending which he had been promising for so long. My concluding observations would be these:

Spending 2.5 per cent of GDP on defence is only a first step. It should allow the armed forces to make good the worst of their existing capability gaps but not much more than that. The figure of three per cent which Starmer has set for some time in the next parliament if conditions allow is, in fact, more or less essential and needs to come much sooner than that. President Trump casually suggested European countries should be spending five per cent of their GDP on defence (rather more than the United States does), and, while that may not be achievable in the short to medium term, it gives a sense of the required scale. To increase our capabilities, invest in new equipment and technology and compensate for a now-almost-inevitable reduction in America’s military footprint in Europe, the UK, like every other European country, has to prepare for a proportion of spending probably nearer 3.5 per cent. (It is worth noting that Poland now spends 4.1 per cent, Estonia 3.4 per cent and Latvia 3.2 per cent. It is not a coincidence that those countries all share a land border with Russia.)

In political and party management terms, Anneliese Dodds’s resignation is a minor inconvenience to Starmer and will not cause any significant disruption. She has neither the inclination nor the heft within the party to be a leading rebel or conspirator, it is currently too early in the parliament for the Prime Minister’s position to be under threat (though that window is closing more quickly than anyone could have expected) and there is insufficient evidence that this is a cause which would rally enough mainstream voters to represent an electoral danger.

Starmer has avoided adverse consequences rather than achieved any major successes. Defence spending will need to rise further, and it is not clear how that will be funded, and even if there is no threat to his position at the moment, he has given opponents within his party another reason to be disappointed in him. Individually, none of these issues—Winter Fuel Payments, the two-child cap, the brouhaha over gifts and hospitality—is politically significant, but they are on the record and they agglomerate. If Starmer finds himself in more serious straits over the next three or four years, they might return to his colleagues’ consciousness with a combined weight which propels them to significance: if not death, then injury by a thousand cuts. This is not over, but then, in politics, nothing ever is.