A PM's department? It almost happened in the 1980s

The public inquiry into the government's handling of the Covid-19 pandemic has raised questions about the centre of Whitehall, but we've been here before

One of the major themes to emerge from the evidence given to the Covid-19 inquiry over the past two weeks has been the inadequacy of the machinery of government at the centre of Whitehall, and the way in which Downing Street, at least under the lazy and easily swayed Boris Johnson, was unable to exert any substantial control over the state to tackle the crisis of the pandemic. This is not a new complaint: there have been calls for greater institutional power in Number 10 for decades.

Under Harold Wilson, this search for more influence and grip manifested itself partly in his increasing reliance on his “kitchen cabinet”. The phrase had first been used to describe an informal, close-knit group of advisers used by United States President Andrew Jackson from 1831, and it crept into British usage, though still referring to American politics, in the 1950s.

In Wilson’s first stint as prime minister (1964-70), it came to be applied to the unelected, extra-parliamentary aides on whom he relied heavily: principally his political secretary, Marcia Williams, later Lady Falkender (of whom a new biography has just been published); but also journalist and academic Bernard Donoughue, reader in politics at the LSE; and Joe Haines, formerly of The Scottish Daily Mail and The Sun, who became the prime minister’s press secretary in 1969. There were other figures like Tommy Balogh, the Hungarian economist from Oxford who was made a peer in 1968 and had a room in the Cabinet Office, and passing parliamentarians like Peter Shore (Wilson’s parliamentary private secretary 1965-66) who was the lead draftsman for Labour’s election manifestos in 1964, 1966 and 1970, and the gossipy and overbearing George Wigg, nominally paymaster general from 1964 to 1967 but more significantly Wilson’s surreptitious link to the intelligence agencies.

Margaret Thatcher, although almost certainly the first prime minister to have any familiarity with an actual kitchen cabinet, did not have anything as semi-formal a group of advisers. In an interview with The Sun in July 1978, she had told Anthony Shrimsley that she would appoint a chief of staff, “a person of some considerable standing”, and in 1979 she gave the job to businessman David Wolfson, to whom she had been introduced in 1975. He was wealthy enough to take the post without a salary, and described his role as “making her aware of the few things that mattered and to make sure that she saw the right people at the right time”. Thatcher described him as “bringing to bear his charm and business experience on the problems of running No 10”. In fact, though, although he retained the role nominally until 1985, he made little institutional impact on Downing Street, and was certainly nothing like the figure of Jonathan Powell, the former diplomat who served as Sir Tony Blair’s chief of staff from 1997 to 2007.

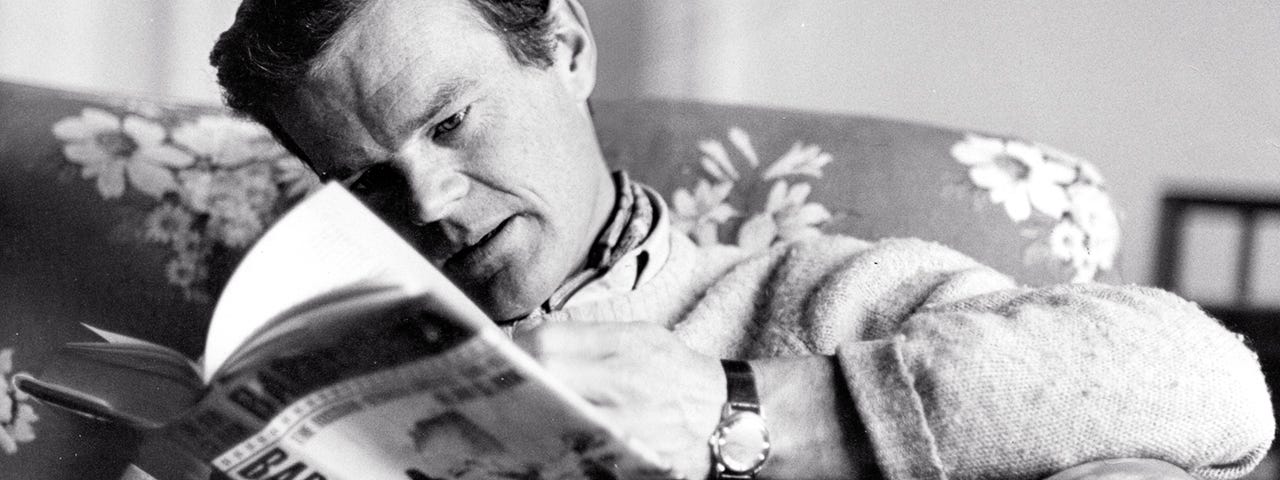

That did not mean no thought was given to the apparatus available to the prime minister. One of the key figures of her early years in Downing Street was Ian Gow, her parliamentary private secretary from 1979 to 1983. An orotund solicitor who was elected MP for Eastbourne in 1974, Gow had been Airey Neave’s deputy in the shadow Northern Ireland team in opposition, and he was ideologically aligned with Thatcher on economic issues. Much more importantly, however, he became a close friend of the prime minister, and regarded her with a devotion of almost mediaeval romanticism. Yet he remained, vitally for the role, his own man: colleagues knew he would keep confidences, and relay messages to Downing Street honestly and accurately.

Gow performed a multitude of roles. Edward Pearce, writing his obituary in 1990 after he was murdered by the IRA, described him as “the nicest sort of non-violent secret-policeman”, who exhaustively took the temperature of the parliamentary party, attending meetings of every faction the Conservatives could offer in those febrile days and taking diligent notes for the prime minister. He adored the House of Commons and spent his hours roaming its dining rooms and bars, always charming and witty, always clubbable but always listening too. However diligent he was for the woman he would later call “the finest chief, the most resolute leader, the kindest friend that any member of this House could hope to serve”, he was only one man.

Already by 1980, Gow was thinking about the future, and had begun to size up Alan Clark, the maverick MP for Plymouth Sutton, as a potential successor if he, Gow, was promoted to ministerial office. In January 1981, according to Clark’s brilliant and invaluable diaries, the pair dined at the Savoy, and Gow asked Clark who should succeed him as PPS when the time came, and asked if he would be interested. “Nothing I would like more outside the Cabinet itself,” Clark responded, with a degree of presumption for a backbencher. He is in some ways the epitome of an unreliable witness, but estimation of the prospect of being Thatcher’s PPS, and therefore of the post itself, is worth noting.

What a coup to overtake, with the most sensational of all ladders, everyone else! The third of fourth most powerful person in the parliamentary party! How they will all cringe and creep! And how well I will do it.

A week later, Clark received a note from Gow confirming their discussion and pledging to keep it on file. But the opportunity never arose.

That same year, 1981, the idea of a prime minister’s department was mooted. It was something which had been in the ether for some time, and would persist, one mechanism to give the head of government greater resources and more direct authority. Most of this consideration was being done below ministerial level, by Gow and John Hoskyns, head of the Policy Unit, on one side and the civil service, especially Sir Robert Armstrong, cabinet secretary, and Clive Whitmore, the prime minister’s principal private secretary. Whitmore thought Thatcher engaged with the notion only in a very narrow way: “when she thought about a Prime Minister’s Department, which was not to a great extent, it was about who would run it for her”.

At this point, there seem to have been two streams of thought. Clive Whitmore felt that Thatcher regarded any enhanced capacity in not just personnel but official terms:

I think that she was thinking much more of whether she should take Robert [Armstrong] and leave the Cabinet Secretary’s traditional role of servicing the whole Cabinet to someone else and put Robert in as head of her Prime Minister’s Department.

At the same time, Hoskyns, a Wykehamist who had been a regular in the Rifle Brigade before going into business in the burgeoning information technology sector of the 1960s and 1970s, was applying a much more logical and systematic approach to the problem.

I was aware of a lack of joined-up government, which is almost endemic in anything complicated and difficult. The threads just do not come together. Whitehall inevitably was organised in that way. It did not have a top brain box. It had clever people in different bits, but not a co-ordinating brain box, which would in itself have to be too political for the Civil Service as constituted to be able to cope with it unless it was a new organisation—slightly hybrid.

There were all sorts of obstacles. Armstrong, prosaically but with force, pointed out that such a department would need a physical home, for which Downing Street was too small. Hoskyns, perhaps ruefully, acknowledged that the Treasury would almost certainly seek to strangle a prime minister’s department at birth: “Would the Treasury, given the realpolitik of any large organisation, give it five minutes? No. I would not if, I were running the Treasury.”

Given all of these obstacles, and a lack of enthusaism from the very top, the idea was laid to rest, at least for a time, at the end of 1981. On 8 December, Gow had a conversation with Hoskyns, the details of which he summarised in a note to Sir Keith Joseph, one of Thatcher’s oldest allies. “We are agreed that a Prime Minister’s Department is not on,” he recorded. The possible ways forward were to strengthen the Number Ten Policy Unit, or to put Hoskyns in charge of the Central Policy Review Staff, the so-called “Think Tank” that Edward Heath had set up within the Cabinet Office in 1971. But the CPRS had been created explicitly to offer long-term, detailed policy advice to ministers collectively, not merely the prime minister, and while Heath, Wilson and Callaghan would speak highly of its contribution, Thatcher found it less impressive and would disband it after the 1983 general election.

Clark, who described Gow as “my closest friend by far in politics”, seems to have spent the first parliament of Thatcher’s premiership on the verge of office without ever quite reaching the front bench (he was appointed under-secretary of state for employment after the 1983 general election). Not a little of this was due to Gow’s patronage, which kept him on Thatcher’s radar and perhaps smoothed over some of the wrinkles in Clark’s personal life, but didn’t quite push him over the edge.

Gow served the full 1979-83 Parliament as Thatcher’s PPS, before being appointed housing minister, improbably enough, at the Department of the Environment. His replacement as the prime minister’s eyes and ears was Michael Alison, MP for Selby. About to turn 57, Alison had already been a reliable if uninspiring minister under Heath as well as Thatcher, and was a privy counsellor; he was the first PPS to be allowed to attend cabinet. Despite his age and experience, and his wartime service in the Coldstream Guards, he was a reserved, ascetic man, utterly unlike Gow, and had no great affection for the thrum of Commons life. He attended far fewer meetings and groups than Gow had, and often absented himself in the evenings. Although generally well enough liked, and regarded as trustworthy, he was not someone who attracted friendship.

Critics soon emerged. Woodrow Wyatt, the peculiar journalist and former Labour MP who was chairman of the Horserace Totalisator Board and had fallen under Thatcher’s spell, gave his verdict without much polish:

Your present PPS may be very agreeable or good but you need as a PPS the kind of person to whom people instinctively say what they’re thinking and confide in them because they like him or trust him or both.

It was a fair assessment. Clark, still intimate with Gow though each was in ministerial harness, recorded a more acerbic judgement in his diaries.

Alison is useless. Saintly but useless… It is extraordinary how from time to time one does get people who have been through Brigade squad, taken their commission and served, seen all human depravity as only one can at Eton and in the Household, and yet go all naïve and Godwatch.

(Alison was an evangelical Christian and had studied at Ridley Hall, the Anglican theological college in Cambridge, and passed his examinations for ordination, after leaving a short career in merchant banking.)

As early as the end of 1983, it was clear that Alison was less effective than his predecessor, but Gow missed the centre of government, too. He began, therefore, to flesh out the recurring idea of a prime minister’s department. The head of the department—in which role Gow saw himself—would sit in cabinet and be the prime minister’s close ally. One stumbling block remained a lack of enthusiasm from the top: although Thatcher was in many ways a radical, she had little interest in machinery of government changes, not least because she had seen the lack of correlation between effort and output under Heath. In her 11-year premiership, she re-united the departments of Trade and Industry in 1983, and separated Health and Social Security in 1988, but otherwise made only very minor changes to Whitehall (such as upgrading the minister of transport to a secretary of state in 1981).

In the middle of December 1983, Gow and Clark met again to discuss Thatcher’s situation. The former rehearsed the complaints about Michael Alison. “She has no-one to confide in,” Clark recorded in his diary, “not to confide in personally that is, although I think she is probably pretty candid on policy matters with Willie [Whitelaw]”. The plan, however, was already emerging, and Clark might as well have been taking dictation from Gow.

How to correct this? Not simply by a change of incumbent. She needed something stronger, more permanent. Something on the lines of a Prime Minister’s Department, with a Lord Privy Seal (or some such) sitting at cabinet, and a couple of PPSs, the senior of whom would be a Minister of State. That’s, Ian strongly implied, where I (whoopee) came into it.

Clark concluded by noting that Gow was “seeing the Lady over Christmas at Chequers and will explore the idea further”. Shortly after Christmas, Clark wrote to Gow, urging him to move the matter forward. “There is a long haul ahead,” he warned, “and these things are better done at moments of tranquillity rather than when the need urgently presses”. He continued to agitate into the New Year, and briefed the learned and respected Times journalist Ronald Butt on the idea.

Lo and behold, on 26 January, Butt’s regular column appeared under the headline A thinking centre for government. It noted an appearance on the BBC’s Question Time by Hoskyns, who had left Downing Street with a knighthood in 1982 and was by this stage about to become director general of the Institute of Directors, during which he had said that ministers had no time to think and that Whitehall lacked the capacity for long-term planning (arguably the specific purpose of the CPRS, which had been wound up the previous summer…). Cribbing almost precisely from Clark, Butt wrote that “an idea has been mooted”.

It is that the Prime Minister should reactivate a dormant sinecure, the office of Paymaster-General, placing the PMG in Number 10 at the head of something like a Prime Ministerial department which could undertake both forward thinking and the coordination of immediate policy making. It could be a replacement of the Think Tank. But instead of inspired amateurs operating outside the mainstream Whitehall machine, it would comprise politicians and civil servants working within the machine. All Whitehall papers would be copied to it.

Butt noted that Thatcher did not at this point favour the idea, despite it coming from “what might be described as impeccably loyal channels”. Perhaps strangely, for an instrument of the Thatcher revolution, he went on to emphasise as an advantage of the new department that it would be within the civil service mechanisms rather than “cranked up by imported outsiders and quasi-administrative initiatives”.

The article did not name names but in every other aspect reflected Gow’s plan as interpreted by Clark. Michael Alison, meanwhile, was aware that some found him wanting when compared to his predecessor. He had not only read but sent to Thatcher an article in the Mail on Sunday in January 1984 by Lady Falkender (Marcia Williams as was, formerly Harold Wilson’s political secretary) which had “revealed” that there were plans to replace him with two PPSs, one a “young, thrusting Tory” who would share the attitudes and concerns of the substantial new intake of MPs from the 1983 general election, the other a more seasoned figure “whose role would be to advise Mrs Thatcher over the occasional whisky at No 10”, which was not-very-sophisticated code for Ian Gow.

In his note, Alison said that he had spoken to the chief whip, John Wakeham, and that they agreed that having two PPSs was not a solution, but he admitted the force of the criticism that he had not been seen in the Commons as much as Gow had been, and would be addressing that as the year went on.

In February, the perhaps-weightier Peter Riddell, political editor of the Financial Times, outlined similar criticisms. The problems, he wrote, focused on “the theme of Downing Street’s being out of touch”. An anonymous Conservative MP said of the PPS role “What you need in that job is a bit of a boozer who will go into the Smoking Room and the bars talking to everyone”, a description which clearly did not fit the ascetic and reserved Alison, and again raised the notion of appointing a second, younger PPS. Wakeham was praised as chief whip, rated for effective than his predecessors Michael Jopling and Humphrey Atkins, but there was a sense that something was missing. Riddell did not mention the idea of a prime minister’s department, but instead referred to rumours that Cecil Parkinson, one of Thatcher’s favourites and until the previous summer her undisputed dauphin, might become more involved in the governmental machine.

(Parkinson had distinguished himself as party chairman from 1981 to 1983, and was to have been appointed foreign secretary after the election to confirm him as the leading candidate to succeed Thatcher when the time came. He had, however, confessed to the prime minister that his lover, Sara Keays, was pregnant with his child and that this would soon become public knowledge. Reluctantly she appointed him to the less prestigious post of trade and industry secretary but he resigned anyway in October when his infidelity became widely publicised. I will write at some point of the massive but subterranean destabilising effect this had on Thatcher: she would never again have a recognised or even likely successor of whom she approved, and it materially affected her conduct of government business and her leadership style, especially as the 1980s wore on.)

The Financial Times article must have struck a nerve, and Alison began drafting a long and detailed rebuttal which he intended to deliver in speech to his constituency annual general meeting. While his injured pride may have been understandable, wider heads saw it was simply adding fuel to the fire, and both Bernard Ingham, the prime minister’s press secretary, and Thatcher herself dissuaded him from making the speech. Thatcher attempted to mollify him: “Michael—You have done a fantastic amount of research—but I think the speech will look as if I am really worried and that I have asked you to make it.”

Perhaps Alison’s reaction to Riddell’s article was decisive in Downing Street. On 29 March, Clark was in the office of one of his ministerial colleagues, Peter Morrison, one of the ministers of state. MP for Chester since 1974, he was the third son of Lord Margadale, former chairman of the 1922 Committee, and had been a very early Thatcher supporter. But he was an unhappy man, his homosexuality a semi-open secret, his preference for younger men not inquired into too closely, and he drank heavily. By this stage he was still tipped for senior office, but the signs were emerging that he might have too much baggage.

However, the casual gossip he related to Clark was, for the latter, devastating.

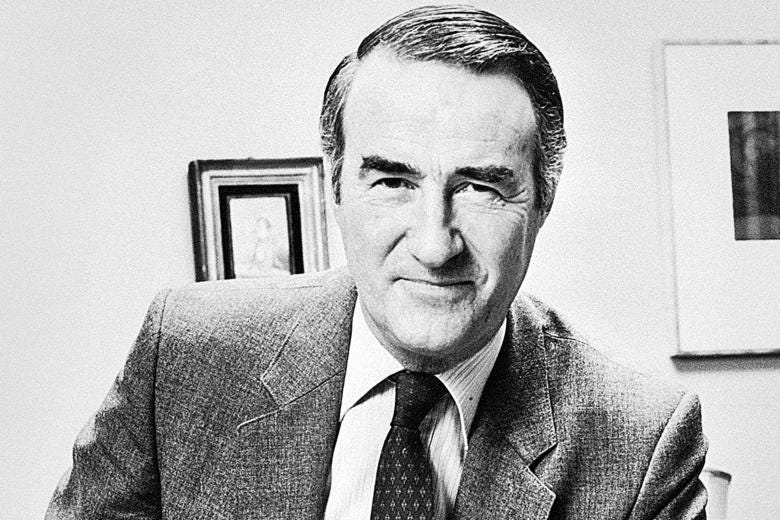

Out of the blue he told me that my suggestions for reforming the Lady’s private office would in all probability be put into effect over Easter But who was going to be put in charge? None other, or so he claimed, than David Young. This is appalling. I hardly know the man. But from what I’ve seen, he’s simply a rather grand H.R. Owen, the big Rolls-Royce dealers’ salesman.

Young was a businessman who had advised Sir Keith Joseph on privatisation at the Department of Industry from 1979. In 1981, Norman Tebbit, employment secretary, had appointed him chairman of the Manpower Services Commission, responsible for co-ordinating employment and training, and had dealt extensively with ministers across the government. Thatcher liked him, partly because he was Jewish: she had an instinctive rapport with Jews, stemming perhaps from her father taking in her elder sister’s Viennese penpal, Edith Mühlbauer, during the Second World War. Young was also “dry” on economics, possessed of a straightforward and practical attitude towards policy issues, and—which spoke eloquently to Thatcher’s heart—a believer in self-help. “God helps those who train themselves,” he observed as chairman of the MSC.

There was worse to come for Clark, who had at least his class’s fair share of knee-jerk anti-Semitism.

Worse was to come. Peter told me that he [Young] was going to have a red box. minister of state rank, and “operate from the Lords”. It was virtually signed up. This threatens to be the end of an era in more senses than one. It finally writes off Ian’s chances of getting back to the epicentre of power, as well as any role for me in that scheme of things.

There was, in a sense, a compliment, in that Downing Street seemed at least to be adopting Gow’s idea of a strengthened centre, albeit with different dramatis personae. Clark, in a last throw of the dice to prevent the changes, using Jonathan Aitken as an intermediary, leaked the information to Peter Riddell.

The Financial Times carried a front-page piece by Riddell on 30 March. Clark was cock-a-hoop. “The fish has taken!” he wrote in his diary. In fact it was not quite so: Riddell had seen through the flimsy subterfuge of using Aitken as a cut-out and had spoken to Bernard Ingham; the Downing Street press secretary had explained that the idea had been under consideration, but would not be going ahead. Still the game was not up. A week later, Riddell was on the front page of the Financial Times again, reporting that Young was indeed going to take a new role. While stressing that “no decision has been taken”, he reported that there would be “a chief of staff role in Downing Street”. One option, as Gow had more or less envisaged, was that “Mr Young would become a life peer and join the Government, probably in the Cabinet, as Paymaster-General or in some similar non-portfolio post”.

Riddell did usefully and briskly sum up a dilemma which still faces Whitehall.

Advocates of having a chief of staff have argued that the Prime Minister needs a senior political aide in Downing Street, not only to co-ordinate the work of her own office but to liaise with other government departments and the Cabinet Office in the implementation of decisions.

The counter-argument was equally well expressed.

When the idea of a Prime Minister’s department was last publicly debated, about a year ago, the suggestion was strongly criticised by Mr Francis Pym, the then Foreign Secretary, on the grounds that it would result in an excessive strengthening of Downing Street and would undermine the position of Whitehall departments.

Peter Hennessy relayed the same tale in The Times. Of Young’s potential role, he wrote “His remit would be to reflect Mrs Thatcher’s political will, be her progress chaser and insure that key elements in her second-term strategy were implemented”. Hennessy noted that idea of a chief of staff had been raised in the 1970s, in opposition, and again after the Falklands War in 1982, and that David Wolfson had gradually withdrawn from his unpaid position (by 1984 he was working one day a week in Downing Street). He also reported the comment of “an admirer” of Young’s that he was “rich, emollient, knows his own mind—he is quite capable of making it an important job”.

There is a persistent sense during these months that the pulling this way and that was being done almost by proxy. In fairness, Thatcher had to look at the bigger picture: on 6 March there had been a walkout at Cortonwood Colliery near Rotherham, and the miners’ strike had begun to unfold. This made the project liable to be drawn out, as no-one who had the time and focus to create a workable solution was equally equipped with the authority to make it happen. How much David Young knew about the prospect of becoming chief of staff is unclear; what is evident is that, while Ian Gow was preoccupied with the machinery of government, Thatcher herself rated it a low priority, which was fair, although urgency and importance are not the same.

As the months rolled by into 1984, it seems that the idea of strengthening the centre faded from people’s minds. Or perhaps it was replaced by other considerations. Parliament sat late that summer, the House of Commons not rising until 1 August, but when it did so, at least, in the days before the wretched September sittings, it adjourned until 22 October. (The House of Lords was due to return on 16 October.) However, on 11 September, it was announced that David Young would join the cabinet as minister without portfolio, and be granted a peerage and membership of the Privy Council to do so. He would advise the prime minister and the government on employment, enterprise and deregulation, absolutely central elements of the Thatcher creed. And on 10 October he was granted a life barony as Lord Young of Graffham. He was the first minister without portfolio since 1974, and the first to sit in cabinet since Peter Shore in 1969-70.

Why had he been given this wider role, then, rather than the job of Thatcher’s enforcer and right hand? As we’ve seen, she was a reluctant Whitehall remodeller, and this solution allowed her to benefit from Young’s advice without major upheaval. But, writing in The Times a few days after the appointment was announced, Bruce Anderson suggested a more profound reason:

The Prime Minister found little comfort in the radicals of her kitchen cabinet. They would tell her that there were simple solutions to all her problems—they each had eight pet but politically utterly impossible schemes. When they were told that the impossible sometimes really is impossible, they would just throw up their hands.

It may be, then, that Thatcher had no particular desire to entrench or empower her close advisers further. And I wonder if there was another reason: I am speculating, but perhaps the prime minister was sceptical of those around her who blamed the systems for their difficulties, suspecting that they were hiding behind excuses?

Young’s appointment to cabinet—he would be promoted to employment secretary a year later—effectively drew the curtain down on the plans for a prime minister’s department. Gow’s ministerial home, the Department of the Environment was busy: having published a white paper, Streamlining the cities: Government proposals for reorganising local government in Greater London and the Metropolitan counties, it intended to legislate to abolish the Greater London Council with what would eventually be the Local Government Act 1985. Gow’s own portfolio, housing and construction, saw the Housing and Building Control Act 1984 and the Housing Defects Act 1984, and there was legislation on finance (Rates Act 1984) and planning (Town and Country Planning Act 1984). Finally, as if to underline that there were bigger fish to fry, on 12 October an IRA bomb exploded in the Grand Hotel in Brighton, where the Conservative Party was holding its annual conference. Thatcher narrowly escaped injury or death; the deputy chief whip, Sir Anthony Berry, was among five people killed; and Norman Tebbit, John Wakeham and Sir Walter Clegg, MP for Wyre, were badly injured.

Without Gow’s impetus, the idea of a prime ministerial hub seemed to fade away. A year later, in September 1985, Gow moved sideways to become a minister of state at the Treasury, but after two months he resigned from government over the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement, which he bitterly opposed. His letter of resignation is suffused with sadness but he remained a passionate, if not uncritical, supporter of Thatcher.

This long, winding tale has some resonance for the picture of Downing Street which is emerging from the Hallett Inquiry. The first is that the direct levers of power within the prime minister’s grasp are relatively limited. One can perfectly well argue that this is constitutionally proper: after all, the prime minister, although appointed by the sovereign, holds office in effect on sufferance from his or her colleagues. If their confidence is lost—as it was disastrously by Boris Johnson last summer—the premier’s position can unravel at great speed. There is perhaps no greater demonstration of that than Thatcher’s presence at an international summit in Paris during the first ballot of the leadership challenge which unseated her. Departmental ministers have their own authority and their own standing, and it is arguably right that the prime minister should have to execute policy through the cabinet.

It is not as if the prime minister has no power. He or she has almost untrammelled ability to hire and fire, and almost all ministers know that they can be dismissed at a moment’s notice. That sharpens the focus. Moreover, addictive though the soap opera can be, we shouldn’t forget that, in broad terms, most parties in government are pointing more or less in the same direction. Just as pressing as giving impetus to policy priorities, in terms of the prime ministerial agenda, is balancing finite resources like funding, personnel and legislative time.

The other important lesson to draw is that there is a distinction between personal and systemic failings, though they can overlap and exacerbate each other. This is an issue which has become badly blurred at the Covid-19 inquiry; even if we agree that Boris Johnson was inadequate as prime minister, were the systems and institutional powers available to him good enough, or were there hard-wired flaws?

In the case of Thatcher, it is a tough judgement. On the face of it, the problem was one of personnel: Gow operated a highly effective service for Thatcher from 1979 to 1983, navigating some very difficult and challenging political circumstances, and did it alone with the background of a cabinet in which, at least until September 1981, Thatcher was in small ideological minority. The three years between her election and the Argentinian invasion of the Falklands Islands were her time of greatest danger, and there were several moments when it seemed she might not, or would not, survive. Yet there was no substantial threat of an existential nature to her premiership. Partly this relied on a Heathite rump which was arrogantly complacent, assuming that the party would return to them; partly it was because the main potential challengers to Thatcher couldn’t effectively organise because they held some of the highest offices of state (Francis Pym, for example, was defence secretary 1979-81, leader of the House of Commons 1981-82 and foreign secretary 1982-83).

It is certainly true that thoughts of changing the system of how Downing Street worked only seem to have become pressing after Gow departed Thatcher’s service in June 1983 (though as we’ve seen the issue had been aired in 1981). Michael Alison throws the matter into sharp relief: he was not just not as good as Gow, but fundamentally unsuited for the job he was required to perform. He was no-one’s confidant, he was not gregarious, he did not listen greedily to others in the way Gow had done. He had no particularly close relationship with Thatcher nor an especially distinguished ministerial track record. One colleague likened him to “a clergyman who has stumbled into a brothel”. And while Thatcher was herself religious, she had none of Alison’s religiosity.

Let’s be realistic. It seems likely that, had a prime ministerial department been constructed around two or three ministers in 1984, it would have made Downing Street more efficient and effective in an administrative sense, but there is a good chance it would have created tension between the centre and departments. That tension would probably have eased within a year or two, and the whole machinery of government would probably have adapted to the new addition, but there might have been some broken careers along the way, and certainly a lot of frayed nerves. However, while it might have improved Thatcher’s ability to push policies forward, there is no reason to think it would have addressed one of the complaints of the post-1983 régime, which was that the prime minister was too remote, too detached and too invisible to her backbenchers. Installing a layer of ministerial (and therefore civil service) responsibility below her would, if anything, have isolated her further.

Margaret Thatcher was not a particularly gregarious person. She didn’t always put people at their ease, she didn’t drink socially to a great extent, she had almost no sense of humour and very little small talk, and she had no particular liking for Parliament’s dining rooms and bars. She had needed Airey Neave to jolly her along when seeking the leadership in 1975, and Gow had served as both her proxy and her walker when she became prime minister in 1979. She did sometimes recede from the embrace of her backbenchers, and that tendency became more pronounced after Gow’s departure in 1983.

However, this problem was separate from the feeling that she had too little power to drive the policy agenda forwards. That was an issue of relationships not with backbenchers but with ministers, whom she saw regularly and frequently. It is possible that a prime minister’s department would have been able to address both problems, but it would not have been doing so in the same way.

Gow’s tenure as Thatcher’s PPS also illustrates an important via media in which a particular personality can mitigate the flaws of a system. Was a single MP acting as parliamentary private secretary sufficient to act as the prime minister’s eyes and ears in Parliament, and actively push her radical ideological agenda through a parliamentary party and even a cabinet which was not fully signed up to it? Clearly not. But Gow’s particular gifts, his relentlessness, his devotion to his chief, his geniality and his appearance of sincerity and empathy allowed him to do much better job of the impossible task than many others would have done.

These ought to be reminders for the Covid-19 inquiry when it comes to its report. Personal and systemic failings are distinct; they can interact; those who hold offices can make systemic flaws worse or ameliorate them, or do neither; and a systemic failure which is made better by an exceptional office-holder has not gone away. These are some of the factors that Baroness Hallett need to keep firmly in mind when they come to tackle the acres of written and oral evidence and try to draw lessons from everything they have been told.

As a postscript, of course, this debate, now 40 years in the past, still goes on. The Downing Street chief of staff still has no universally accepted role or parameters, and the job has been held by political and civil service employees, and even, briefly, a minister (Steve Barclay, chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, was Johnson’s chief of staff from February to July 2022). There is no “prime minister’s department”, and arguments about the role and scope of the Cabinet Office go on. It will be interesting to see what changes are made if Sir Keir Starmer becomes prime minister and Whitehall veteran Sue Gray comes with him as his chief of staff. Watch this space.

This is so interesting. Thank you.