Workers of the world, unite!

If the Labour Party, of all organisations, cannot say what it means by "working people", there is something badly wrong with our political discourse

The English language is an arsenal of weapons; if you are going to brandish them without checking to see whether or no they are loaded you must expect to have them explode in your face from time to time. (Stephen Fry, The Liar)

One of the most over-used aphorisms in public life is that politics is the art of the possible. The Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck was quoted in 1867 as saying “politics is the art of the possible, the attainable—the art of the next best”, and Rab Butler used the phrase for the title of his archly world-weary 1971 autobiography. But politics is, and has to be, more than that: it must also be the art of making what was thought impossible possible, of effecting revolutionary change. Think of the abolition of the slave trade, the Great Reform Act of 1832, Shaftesbury’s reforms of child labour, the Beveridge Report, the deregulation of London’s financial markets in 1986, the UK’s exit from the European Union: each seemed inconceivable and yet was achieved.

In that sense, therefore, politics is also about persuasion, and that means that it is about language. As a writer I am deeply, intrinsically fascinated by and attached to language, and I take enormous joy in it too. It is one of the reasons for my devotion to Stephen Fry (see top), as I wrote a couple of years ago. For politicians, trying to create a powerful, resonant, persuasive message, the selection of words is of towering importance, and it is something to which good politicians and their advisers devote a huge amount of time. English, after all, has a much wider vocabulary than most languages—the Oxford English Dictionary estimates there are around 170,000 words in current usage, with another 47,000 described as “obsolete”—so whenever you decide how to say something, you are making a number of choices and, if you are in the public spotlight, should be calculating carefully the potential meanings and effect of each possibility.

A case in point: there was outrage in January 1978 when Margaret Thatcher, then leader of the Opposition, said in an interview for Granada TV’s World in Action, while discussing immigration, that “people are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture”. Her use of the word “swamped” was interpreted, rightly or wrongly, as framing immigration negatively and as an unwelcome arrival of “others”, and the same word would cause controversy again in 2014, when defence secretary Michael Fallon spoke of “whole towns and communities being swamped by huge numbers of migrants”. Home secretary Suella Braverman raised the stakes in October 2022 when she described illegal migration as “the invasion on our southern coast”.

Words matter. This means that it is no footling semantic issue that the government has become so enmeshed in confusion over what ministers mean when they refer to “working people”. On Wednesday, the deputy prime minister, Angela Rayner, came to the House of Commons to stand in for Sir Keir Starmer, who was on his way to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Samoa, at Prime Minister’s Questions. As convention dictates, the leader of the Opposition, Rishi Sunak, also stepped back for the occasion, so the Conservative Party’s questioning was led by the shadow deputy prime minister, Sir Oliver Dowden. His opening salvo was simple.

What is the Deputy Prime Minister’s definition of working people?

Neither Rayner nor Dowden would be considered in the front rank of parliamentary orators, and the deputy prime minister’s answer was dismissive.

The definition of “working people” is the people who the Tory party have failed for the past 14 years.

Dowden, however, realised he had found a weakness and, like any competent politician, pressed harder.

The Deputy Prime Minister stood on a manifesto promising not to raise taxes on working people. It now appears that she cannot even define who working people are, so I will give her another go. There are five million small business owners in this country; are they working people?

It is understandable that cabinet ministers, backed by a majority of more than 170 in the House of Commons, have little time for the scrutiny of the diminished Official Opposition. Again Rayner was blustery and aggressive.

I do not know how the shadow Deputy Prime Minister can stand there with a straight face when it was the small businesses—the working people of this country—that paid the price of the Conservatives crashing the economy, sending interest rates soaring. I think he needs to learn his own lessons in opposition.

Labour backbenchers may have cheered, but Dowden, who is expected to step down from the front bench next month (and, it is rumoured, may leave the House altogether) seemed demob-happy and persisted.

I think the whole House will have heard the Deputy Prime Minister disregard five million hard-working small business owners. These are the publicans, the shopkeepers, the family running a local café. None of those count as working people to her. Labour gave a clear commitment not to raise national insurance. The independent Institute for Fiscal Studies has given its view on this. It says that raising employer national insurance is “a tax…on working people”. Even the Chancellor said that raising employer national insurance was a “jobs tax” that will “make each new recruit more expensive and increase the costs to business”. So does the Deputy Prime Minister agree with the IFS and her own Chancellor?

This kind of close-reading, almost pernickety argumentation is not something at which Rayner (whom I by no means dismiss, and who has some genuinely formidable qualities as a politician) excels.

I remember what the Conservatives said to business. What was it? “Eff business”, whereas this party held an international investment summit last week, which put about £63 billion into our economy. We are pro-business, pro-worker and getting on with fixing the mess that they left behind.

She had clearly decided to ignore the question by this stage, using the (rapidly fading) flush of victory and the impotence of the Opposition to ride out any theoretical awkwardness and pretend that Dowden was not there, or at least there only as a target for political jibes. Dowden, however, on the fourth of his allotted six questions, was not quite finished.

I think we can take it from that answer that the Deputy Prime Minister does not agree with the IFS, and I suppose it should not come as a surprise that she does not agree with her Chancellor, but does she agree with this: “Working people will pay… when employers pass on the hike in national insurance”? Those are her words, so does she at least agree with herself?

In theory, and in terms of logical, these were serious blows. Dowden was pressing on a point of incoherence or at least inconsistency on the part of the government. In a competitive debating environment, the judges would have been nodding approvingly and making notes to score him highly. But the House of Commons is a political amphitheatre, and Rayner could see light at the end of the tunnel if she ploughed ahead.

What I am incredibly proud of is that this week, this Government brought in a new employment Bill that will raise the living standards of 10 million workers. Would the shadow Deputy Prime Minister like to apologise for the hike in taxes—they are at a 70-year high—that he put on working people, the crashing of the economy and the disaster that he left behind?

Dowden sensibly moved on to other matters for his final questions. He had made his point insofar as it mattered in that context and his remarks were on the record. Rayner had provide no answers, no clarification, no progress towards what the government means when it talks of “working people”. That lack of precision matters, both politically and intellectually.

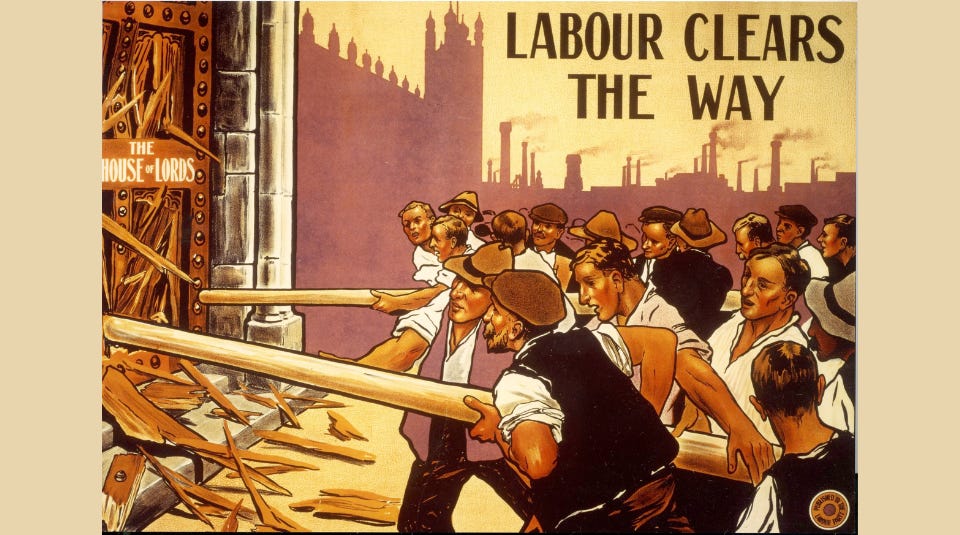

Let us go back a few steps. The argument over “working people” stems in immediate terms from the Labour Party’s manifesto for the general election. The document used the phrase “working people” 18 times, which on the face of it should hardly surprise us. Labour was, after all, formed explicitly as the representative body of the workers: the Labour Representation Committee was created in February 1900 as a coordinated parliamentary group by the Trades Union Congress, the Independent Labour Party, the Social Democratic Federation and the Fabian Society, and its purpose was to act “in the direct interests of labour”.

The world of 1900, however, was very different from today, in the twilight of Queen Victoria’s reign, with an all-male electorate of only 6.7 million in a nation of 41.5 million people; the 19-strong cabinet headed by the 3rd Marquess of Salisbury contained nine peers to 10 MPs, who between them compromised 11 Oxford graduates and three from Cambridge. The only one of them who might possibly have thought of himself as one of the “working people” was Joseph Chamberlain, the colonial secretary, who had spent his first years in his father’s shoe-making business. Of his cabinet colleagues, 11 were self-sufficient aristocrats and landowners, and five were barristers.

The notion of “working people” at the time of Labour’s birth was understood fundamentally and primarily as referring to the working class, and that, in turn, meant those who undertook manual labour: agricultural workers, miners, shipbuilders, factory workers and (the largest category) domestic servants. Manifestly that is not the demographic reality which was in the minds of those who drafted this year’s Labour manifesto. But it would be naïve to assume that it is a phrase which refers simply to those who are in paid employment of any kind, currently around 33.2 million of us. The phraseology of the manifesto uses “working people” to appeal to an idea of virtuous, hard-working, hard-pressed “ordinary” people; the country must “once again serve[s] the interests of working people”, the economy has undergone “stuttering growth and a cost-of-living crisis that hurt working people”, the government seeks to “improve the lives of working people” and will “ensure taxes on working people are kept as low as possible”.

In a general sense, this is a classic political technique of very vaguely defining a group to which almost all of us can plausibly imagine we belong, or at least could belong. The manifesto portrays “working people” as deserving of help and the rightful recipients of the service of the state, a group whose lives can and must be improved. If reforming the economy is to involve give and take (and it always does), there is no sense that “working people” will be expected to give.

This is the crux, because it relates to the measures we are being briefed to expect in next week’s Budget. Sir Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves spent the years before the general election determined to impress on the electorate that the Labour Party was fiscally prudent and responsible, that there need be no fear of enormous and unfunded increases in public spending or, critically, significantly higher taxation. (Even now, more than 30 years on, there is a frightening folk memory on the left of “Labour’s tax bombshell” in 1992.)

The section of the Labour manifesto entitled “Economic stability” addressed this issue directly and—it would prima facie seem—straightforwardly:

The Conservatives have raised the tax burden to a 70-year high. We will ensure taxes on working people are kept as low as possible. Labour will not increase taxes on working people, which is why we will not increase National Insurance, the basic, higher, or additional rates of Income Tax, or VAT.

While there were anxieties that this put considerable limitations on a Labour chancellor’s freedom of action, it had the virtue of being clear and reassuring. The ordinary voter could read that commitment and fairly be certain that he or she could vote Labour without risking an increase in National Insurance, income tax or VAT.

Now it appears not to be so simple. There have been persistent rumours, which the government has not categorically denied, that the chancellor will increase the National Insurance contributions levied on employers as part of the Budget. There is certainly a distinction between the NI paid by employees and employers: the former is taken from regular pay, while the latter is paid directly by the employer to the government. This allows the government and its supporters to insist that such a measure would remain consistent with Labour’s manifesto commitment, because the “increase [in] National Insurance” would not be falling on “working people”.

This is, to begin with, disingenuous at best. Many economists agree that a higher level of NI contribution on employers would lead to lower pay, fewer job opportunities and fewer working hours than otherwise, which would have a direct impact even on the most favourable interpretation of “working people”. That would be at best a jesuitical approach to the manifesto.

More broadly, though, if we are to accept Labour’s line of argument that raising employers’ NI contributions would be consistent with its promise that it would “not increase taxes on working people”, we must, by definition, draw a distinction between “working people” and employers. To put it another way, if you employ anyone and are liable for NI contributions on that basis, you do not fall into the category of “working people” as defined by the Labour Party. That is why Oliver Dowden skilfully referred to “five million hard-working small business owners… the publicans, the shopkeepers, the family running a local café”. The logic is simple: if the government is not breaking its manifesto commitment, then those are not “working people”. There is no other way to resolve the contradiction.

So what have ministers said when pressed on their conception of “working people”? Before the election, Sir Keir Starmer was interviewed on LBC by Nick Ferrari, who asked him to define the phrase.

The person I have in my mind when I say working people is people who earn their living, rely on our services, and don’t really have the ability to write a cheque when they get into trouble.

It is worth noting that this was not an exclusive definition. Starmer—a very distinguished lawyer, remember, and therefore professionally careful with words and definitions—referred to “the person I have in my mind when I say working people”, so he was talking illustratively rather than definitionally. We could not reasonably say that “working people” are defined by a lack of savings (“the ability to write a cheque”).

Inevitably this woolly framing did not settle the matter. The following day, asked for greater clarity, Rachel Reeves told Sky News:

Working people are people who go out to work and work for their incomes. Sort of by definition, really, working people are those people who go out and work and earn their money through hard work.

Asked if she agreed with Starmer’s additional proposition, that “working people” were those without savings, she prevaricated.

Some people, who go out to work haven’t been able to build up savings. Many other people who go out to work, have had to run down their savings. But there are people who do have savings, who have been able to save up and those are working people as well.

This was no help: “working people” were those who did, or did not, have savings.

Last weekend, two more ministers, appearing on Sky News, were asked to clarify what the government meant by “working people”. Stephen Kinnock, minister of state for care at the Department of Health and Social Care, refused to say that people earning more than £100,000 would not be subject to higher taxation. His boss, health secretary Wes Streeting, was more forthcoming but not necessarily more helpful.

When I’m thinking about this budget and its consequences, I’m actually not thinking about people on my salary or your salary. I’m thinking about people like my mum, who’s a cleaner, or my dad, who’s a car salesman. People who are on lower or middle income who get towards the end of the month and find they’ve got more month left than they have the money… I am not worried about me, I am not worried about you, but I am worried about people who are struggling to make ends meet at the moment.

Streeting hints at a possible definition: “working people” are limited to those below a certain level of income (the exact level is secondary). Or, to put it another way, if you earn more than a certain amount, the government does not regard you as “working people” with all the benevolence and advantages it has set out at length.

Matt Chorley on BBC Radio 5 Live, interviewing the chancellor earlier in the week, made another attempt. Would people earning more than £100,000 face tax rises, and were they, therefore, outwith the government’s definition of “working people”?

We said that… we wouldn’t increase the taxes, the main taxes that working people pay, so income tax—all rates—National Insurance and VAT. So those taxes that working people pay, we’re not increasing those taxes in the budget.

This conforms broadly to the tacit answer implied by what Kinnock and Streeting had said.

The prime minister, in Samoa for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, was unable to escape this nagging dispute. He was asked if someone who had a job, but who also received income from shares or property, fell within the category of “working people”. His response was “Well, they wouldn’t come within my definition”. However, Downing Street later clarified, in the words of The Financial Times, “that it was possible for a working person to have a small amount of shares, for example in a stock market individual savings account”. So, again, “working people” do not own shares, unless they do.

It is worth this detailed examination because Labour itself made the status of “working people” a central issue. It said that the group would not be subjected to greater taxation, but did so in a context which encouraged a reasonable observer to infer a maximal definition. Now, as the chancellor prepares to increase the tax which some people, specifically employers, will have to pay, the government is frantically trying to narrow the limits of who “working people” are to prove that its manifesto commitment remains intact.

It is obvious that “working people”, for the government, does not simply mean people who earn income from their own economic activity (excluding those who are recipients of passive income like rent or interest on capital). It is narrower than that. There seem to be two elements to the category as imagined by ministers. The first is that it comprises only those who have a direct employer, that is, people who work for a larger entity, whether it be a small business or a multinational corporation. It could conceivably be stretched to include the self-employed, but it cannot, logically, include those who themselves employ other people, because they will be liable for higher NI contributions as employers.

The second element is a financial one. When Starmer pointed to people who “rely” on public services—presumably those who use public transport, do not send their children to independent schools and who cannot afford private healthcare, rather than choose not to use it—and those without substantial savings, his meaning was clear: “working people” are those on middle to low incomes. That was more or less confirmed by Stephen Kinnock and Wes Streeting. It is a slightly arbitrary ceiling, but it is fair to assume, given what they have said, that “working people” fall into a category which, in ministers’ minds, does not earn above £100,000 a year or so.

It would have been perfectly defensible, both intellectually and politically, to make this explicit, to have said that those on middle to low incomes are already sufficiently hard-pressed and therefore will not be expected to pay more tax than they already do. But that is not what Labour said. Instead, it has consistently used moral overtones. The manifesto, as I set out above, presented “working people” in virtuous terms, and Reeves has reinforced this, defining them as those who “earn their money through hard work”. Note, “hard” work. Is hard work exclusive to those towards the lower end of the income scale?

It is just possible to bend words and meaning in such a way as to argue that the government is not breaking the letter of its manifesto commitment not to increase taxes for working people, though raising NI on employers clearly drives a coach and horses through the spirit if the promise. That is good sport for the Opposition, and again chips away at the pious attitude that Sir Keir Starmer has tended to strike. But a fair-minded observer would have to concede that Starmer, and Reeves and other members of the government, would hardly be the first politicians to break a publicly expressed promise. Most famously, perhaps, George H.W. Bush, accepting the Republican Party’s nomination for president of the United States at its convention in New Orleans in August 1988, issued a striking hostage to fortune which would return to haunt him:

I’m the one who will not raise taxes. My opponent now says he’ll raise them as a last resort, or a third resort. But when a politician talks like that, you know that’s one resort he’ll be checking into. My opponent won’t rule out raising taxes. But I will. And the Congress will push me to raise taxes and I’ll say no. And they’ll push, and I’ll say no, and they’ll push again, and I’ll say, to them, “Read my lips: no new taxes.”

These things happen, and they do not help a party’s credibility or trustworthiness.

I cannot avoid the feeling that there is something deeper which is colouring the government’s hazy and confused grapplings with a phrase it made so prominent. Labour supporters will wave this aside, as they are entitled to do, and they have an overwhelming parliamentary majority to assist them, though they must also accept that the prime minister is unprecedentedly unpopular so soon after an election victory. Only 19 per cent of those surveyed recently by YouGov feel that the government is doing a good job, while 26 per cent made the same estimation of Sir Keir Starmer.

Fundamentally, the current Labour hierarchy is deeply uncomfortable with monetary success and wealth creation. I proposed this idea in The Critic at the end of 2023. I noted that one of the most important transformations of the Labour Party under Sir Tony Blair was its acceptance of personal wealth, and recalled Lord Mandelson’s remark to Hewlett-Packard executives in 1998: “We are intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich”. By contrast, Starmer’s Labour has long been “steeped in an assumption that the state is the best and most virtuous expression of economic activity”, meanwhile believing that “private enterprise is the home of ‘excess profits’ and non-domiciled tax status”. My conclusion is standing the test of time:

What lurks beneath, creeping out only in hint and nuance and language, is that the Labour Party has rolled back the Blairite revolution in this one intellectual respect. So far from being intensely relaxed, it gathers together its traditions of trade unionism, non-conformity and egalitarianism, and it simply cannot face up to the reality of wealth creation through private enterprise. It is too raw, too messy, too ugly, too bare-knuckle. These people may exist, Labour accepts, but you don’t have to have them at your table.

The wrangling over the definition of “working people” is only reinforcing me in this view. For Starmer and Reeves, virtuous and admirable people are modestly paid employees (Lord Alli may be exempt from this taxonomy). Their financial affairs are straightforward, with no significant savings, no share ownership and no unearned income from property—there is nothing to draw upright politicians into any difficult choices or decisions about what should and should not be taxed, or what people should or should not spend substantial amounts of money on. These honourable citizens are paid a salary, from which the government subtracts income tax and National Insurance, and they pay VAT on their purchases. More or less, that is that.

People outside this category are more challenging. Their relationship with the state is more complicated as they often employ others as well as themselves being employed, they sometimes receive income in several different ways and they have assets which are attractive to covetous Treasury eyes. I suggested in my weekly City AM column in August that Rachel Reeves “regards private wealth as an easy source of additional revenue”, and I certainly have seen no evidence of a strong bias in favour of letting taxpayers keep as much of their own money as possible.

This reflects an age-old struggle within Labour, and socialism more generally, to accommodate the concept of capitalism. The economy is framed in moral and ethical terms, so that we talk, almost without noticing, about “excess profits”, the inevitable corollary of which is that there is, somehow defined, a “correct” or “acceptable” or even “virtuous” amount of profit beyond which enterprise should not go. It was a remarkable statement when, in 1973, Edward Heath described mining conglomerate Lonrho and its swashbuckling chief executive, “Tiny” Rowland, as “the unpleasant and unacceptable face of capitalism”; but a remark which raised eyebrows from a Conservative premier is more representative of an ongoing strand of Labour thought.

When they talked about “working people”, Sir Keir Starmer, Rachel Reeves and others knew, in truth, who they meant. They were a similar group to the one Theresa May had summoned up when she took office and were dubbed “Jams”, or “just about managing”, the “squeezed middle” over whom George Osborne and Ed Miliband had wrestled in the early 2010s. But the current government has taken this further, hedging “working people” with a faint sanctity and presenting them not only as a protected class but one which is much more tightly defined that voters were led to imagine.

The political brouhaha over the government’s definition of “working people” will pass and be forgotten, as, in truth, most political brouhahas are (ask the proverbial man on the Clapham omnibus to explain the downfall of Damian Green in 2017, the scandal that claimed Geoffrey Robinson’s political career in 1998, the Westland affair or the Poulson scandal). It may chip away a little further at the government’s reputation, reinforce by a small measure the public’s feeling that politicians are by nature mendacious and not to be believed, but that will be its extent.

Its insight into the government’s conception of the economy, its very Weltanschauung, is much more important. Starmer and Reeves have emphasised again and again the importance of economic growth, its central role in everything else the government wants to do. They have banged the drum for the recent International Investment Summit held at the Guildhall. Growth is only possible through the private sector, through private enterprise and commerce and free trade, these capitalist superpowers, but there is not always as much virtue or morality about growth as we might like. That is something the government will have to confront, and it does not seem ready yet.

https://www.cityam.com/who-will-bang-the-drum-for-free-enterprise/

“The private sector knows he is likely to be the next prime minister, with a substantial majority, but there is also a suspicion that he neither understands nor especially likes how the British economy, away from the public sector, actually works.”